A Taste of Scotland?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel On behalf of all the staff we would like to congratulate you on your upcoming wedding. Set in the former RAF camp, in the village of Boddam, the building has been totally transformed throughout into a contemporary stylish hotel featuring décor and furnishings. The Ballroom has direct access to the landscaped garden which overlooks Stirling Hill, making Buchan Braes Hotel the ideal venue for a romantic wedding. Our Wedding Team is at your disposal to offer advice on every aspect of your day. A wedding is unique and a special occasion for everyone involved. We take pride in individually tailoring all your wedding arrangements to fulfill your dreams. From the ceremony to the wedding reception, our professional staff take great pride and satisfaction in helping you make your wedding day very special. Buchan Braes has 44 Executive Bedrooms and 3 Suites. Each hotel room has been decorated with luxury and comfort in mind and includes all the modern facilities and luxury expected of a 4 star hotel. Your guests can be accommodated at specially reduced rates, should they wish to stay overnight. Our Wedding Team will be delighted to discuss the preferential rates applicable to your wedding in more detail. In order to appreciate what Buchan Braes Hotel has to offer, we would like to invite you to visit the hotel and experience firsthand the four star facilities. We would be delighted to make an appointment at a time suitable to yourself to show you around and discuss your requirements in more detail. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Silver Tassie

The Silver Tassie MY BONIE MARY An old Jacobite ballad rewritten by the Bard. A silver tassie is a silver goblet and the Ferry which is mentioned in the poem is Queensferry, now the site of the two bridges which span the Forth, a short distance from Edinburgh. Go fetch to me a pint 0' wine, And fill it in a silver tassie; That I may drink before I go, A service to my bonie lassie: The boat rocks at the Pier 0' Leith, Fu' loud the wind blaws frae the Ferry, The ship rides by the Berwick-Law, And I maun leave my bonie Mary. maun = must The trumpets sound, the banners fly The glittering spears are ranked ready, The shouts 0' war are heard afar, The battle closes deep and bloody. It's not the roar 0' sea or shore, Wad mak me longer wish to tarry; Nor shouts 0' war that's heard afar- It's leaving thee, my bonie Mary! Afion Water This is a particularly lovely piece which is always a great favourite when sung at any Bums gathering. It refers to the River Afion, a small river, whose beauty obviously greatly enchanted the Bard. Flow gently, sweet Afcon, among thy green braes! braes = banks Flow gently, I'll sing thee a song in thy praise! My Mary's asleep by thy murmuring stream - Flow gently, sweet Afton, disturb not her dream! Thou stock-dove whose echo resounds thro' the glen, stuck dm =a wood pipn Ye wild whistling blackbirds in yon thorny den, yon = yonder Thou green-crested lapwing, thy screaming forbear, I charge you, disturb not my slumbering Fair! How lofey, sweet Afion, thy neighbouring hills, Far markd with the courses of clear, winding -

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

Scottish Menus

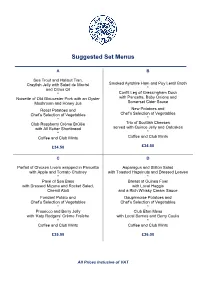

Suggested Set Menus A B Sea Trout and Halibut Tian, Crayfish Jelly with Salad de Maché Smoked Ayrshire Ham and Puy Lentil Broth and Citrus Oil * * Confit Leg of Gressingham Duck Noisette of Old Gloucester Pork with an Oyster with Pancetta, Baby Onions and Somerset Cider Sauce Mushroom and Honey Jus Roast Potatoes and New Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Club Raspberry Crème Brûlée Trio of Scottish Cheeses with All Butter Shortbread served with Quince Jelly and Oatcakes * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £34.50 £34.50 C D Parfait of Chicken Livers wrapped in Pancetta Asparagus and Stilton Salad with Apple and Tomato Chutney with Toasted Hazelnuts and Dressed Leaves * * Pavé of Sea Bass Breast of Guinea Fowl with Dressed Mizuna and Rocket Salad, with Local Haggis Chervil Aïoli and a Rich Whisky Cream Sauce Fondant Potato and Dauphinoise Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Prosecco and Berry Jelly Club Eton Mess with ‘Katy Rodgers’ Crème Fraîche with Local Berries and Berry Coulis * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £35.00 £36.00 All Prices Inclusive of VAT Suggested Set Menus E F Confit of Duck, Guinea Fowl and Apricot Rosettes of Loch Fyne Salmon, Terrine, Pea Shoot and Frissée Salad Lilliput Capers, Lemon and Olive Dressing * * Escalope of Seared Veal, Portobello Mushroom Tournedos of Border Beef Fillet, and Sherry Cream with Garden Herbs Fricasée of Woodland Mushrooms and Arran Mustard Château Potatoes and Chef’s Selection -

126613742.23.Pdf

c,cV PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME XXV WARRENDER LETTERS 1935 from, ike, jxicUtre, in, ike, City. Chcomkers. Sdinburyk, WARRENDER LETTERS CORRESPONDENCE OF SIR GEORGE WARRENDER BT. LORD PROVOST OF EDINBURGH, AND MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE CITY, WITH RELATIVE PAPERS 1715 Transcribed by MARGUERITE WOOD PH.D., KEEPER OF THE BURGH RECORDS OF EDINBURGH Edited with an Introduction and Notes by WILLIAM KIRK DICKSON LL.D., ADVOCATE EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1935 Printed in Great Britain PREFACE The Letters printed in this volume are preserved in the archives of the City of Edinburgh. Most of them are either written by or addressed to Sir George Warrender, who was Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1713 to 1715, and who in 1715 became Member of Parliament for the City. They are all either originals or contemporary copies. They were tied up in a bundle marked ‘ Letters relating to the Rebellion of 1715,’ and they all fall within that year. The most important subject with which they deal is the Jacobite Rising, but they also give us many side- lights on Edinburgh affairs, national politics, and the personages of the time. The Letters have been transcribed by Miss Marguerite Wood, Keeper of the Burgh Records, who recognised their exceptional interest. Miss Wood has placed her transcript at the disposal of the Scottish History Society. The Letters are now printed by permission of the Magistrates and Council, who have also granted permission to reproduce as a frontispiece to the volume the portrait of Sir George Warrender which in 1930 was presented to the City by his descendant, Sir Victor Warrender, Bt., M.P. -

May and June 2020 Newsletter

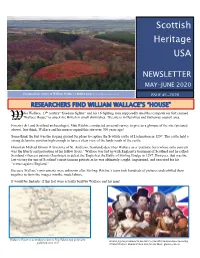

Scottish Heritage USA NEWSLETTER MAY-JUNE 2020 Presumed site of 0ne of William Wallace’s hidden forts (©FLS by Skyscape survey 2020) ISSUE #1-2020 RESEARCHERS FIND WILLIAM WALLACE’S “HOUSE” ilia Wallace, 13th century “freedom fighter” and his 16 fighting men supposedly used this campsite (or fort) named W “Wallace House” to attack the British in small skirmishes. The site is in Dumfries and Galloway council area. Forestry & Land Scotland archaeologist, Matt Ritchie, conducted an aerial survey to give us a glimpse of the site (pictured above). Just think, Wallace and his men occupied this site over 700 years ago! Some think the fort was the staging ground for plans to capture the Scottish castle of Lochmaben in 1297. The castle held a strong defensive position high enough to have a clear view of the lands south of the castle. Historian Michael Brown (University of St. Andrews, Scotland) describes Wallace as a “patriotic hero whose only concern was the liberty and protection of his fellow Scots.” Wallace was fed up with England’s treatment of Scotland and he rallied Scotland’s fiercest patriots (Jacobites) to defeat the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297. However, that was the last victory for one of Scotland’s most famous patriots as he was ultimately caught, imprisoned, and executed for his “crimes against England.” Because Wallace’s movements were unknown after Stirling, Ritchie’s team took hundreds of pictures and cobbled them together to form the images into the model above. It would be fantastic if this fort were actually built by Wallace and his men! Wallace’s House on an Ordinance Survey First Edition map of the area, Several figures prominent in the history of Scottish Independence including published circa 1857 William Wallace, Bonnie Prince Charlie and Mary, Queen of Scots. -

The Mother Tongue J Derrick Mcclure

The Mother Tongue J Derrick McClure We are grateful to J Derrick McClure for writing this article for inclusion on the Scots Language Centre website. ********** The old Scots tongue, the language that can still be heard in the mouth of many a lad and lass from the Shetland Isles to the Mull of Galloway, has as wonderful a history as any of the languages of the world. To understand the life of any language, we must know two things. We must know the structure of the language itself: its sounds and spelling, its grammar, its words. And we must also know what the language means, and has meant, to the people who speak it. There is no language that has not changed with the passing of the years: the English of Shakespeare is not the English spoken today. A language can change so much that it becomes an entirely different thing: French, Italian, Spanish and several other European tongues were all one and the same language, Latin, many centuries ago. And a language can simply die, leaving no trace: the Indians of America and Canada have now for the most part forgotten their mother tongues and speak only English, and many people fear that if we are not careful our own Gaelic and Scots will go the same way. Gaelic is related to Irish; Scots is related to English. What that means is that there was once a single language - Old Irish for one of the pairs, Old English (sometimes called "Anglo-Saxon") for the other - which divided into two, developing and changing in different ways in the kingdoms of Scotland and Ireland, or Scotland and England. -

The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges

THE ATLAS OF DIGITISED NEWSPAPERS AND METADATA: REPORTS FROM OCEANIC EXCHANGES M. H. Beals and Emily Bell with additional contributions by Ryan Cordell, Paul Fyfe, Isabel Galina Russell, Tessa Hauswedell, Clemens Neudecker, Julianne Nyhan, Mila Oiva, Sebastian Padó, Miriam Peña Pimentel, Lara Rose, Hannu Salmi, Melissa Terras, and Lorella Viola and special thanks to Seth Cayley (Gale), Steven Claeyssens (KB), Huibert Crijns (KB), Nicola Frean (NLNZ), Julia Hickie (NLA), Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen (NLF), Chris Houghton (Gale), Melanie Lovell-Smith (NLNZ), Minna Kaukonen (NLF), Luke McKernan (BL), Chris McPartlanda (NLA), Maaike Napolitano (KB), Tim Sherratt (University of Canberra) and Emerson Vandy (NLNZ) Document: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059 Dataset: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560110 Disclaimer: This project was made possible by funding from Digging into Data, Round Four (HJ-253589). Although we have directly consulted with the various institutions discussed in this report, the final findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the discussed database providers or the contributors’ host institutions. Executive Summary Between 2017 and 2019, Oceanic Exchanges (http://www.oceanicexchanges.org), funded through the Transatlantic Partnership for Social Sciences and Humanities 2016 Digging into Data Challenge (https://diggingintodata.org), brought together leading efforts in computational periodicals research from six countries—Finland, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to examine patterns of information flow across national and linguistic boundaries. Over the past thirty years, national libraries, universities and commercial publishers around the world have made available hundreds of millions of pages of historical newspapers through mass digitisation and currently release over one million new pages per month worldwide. -

A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770 Mollie C. Malone College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malone, Mollie C., "A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626149. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0rxz-9w15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mollie C. Malone 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 'JYIQMajl C ^STIclU ilx^ Mollie Malone Approved, December 1998 P* Ofifr* * Barbara (farson Grey/Gundakerirevn Patricia Gibbs Colonial Williamsburg Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR’S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 17 CONCLUSION 45 APPENDIX 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 i i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank Professor Barbara Carson, under whose guidance this paper was completed, for her "no-nonsense" style and supportive advising throughout the project. -

The Young Housekeeper

Blank Page Blank Page Blank Page Blank Page YOUNG HOUSE-KEEPER. Blank Page THE YOUNG HOUSE-KEEPER, OR THOUGHTS ON F OOD AND COOKERY. BY WM. A. ALCOTT, Author of the Young Husband, Young Wife, Young Woman's Guide, House I Live in, &c. &c. S ixth Stereotype Edition BOSTON: WAITE, PEIRCE & COMPANY, No. 1 Cornhill. 1846. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1838, by W m. A. A lcott, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts. G. C. R a n d Printer, 3 Cornhill. CONTENTS CHAPTER I. DIGNITY OF THE HOUSE-KEEPER Silent influence of the house-keeper. Her character as a teacher and educator. Should the mother be the house-keeper? Vulgar notions. Anecdote. Dignity of the house-keeper asserted. She is, in some respects, a legislator—a counsellor—a minister—a missionary— a reformer—a physician............................................ 21—48 CHAPTER II. FIRST PRINCIPLES. 1. Obey the dictates of conscience. 2. Dare to disobey the mandates of fashion. 3. Dignify your profession. 4. Keep the house yourself, as much as possible. 5. Whatever is worth doing, is worth doing well. 6. Importance of securing the aid of the husband and others. 7. Anecdote and reflections...................... 49—60 CHAPTER III. HAVING A PLAN. Why a plan is indispensable. Hour of rising. Ar rangements. Breakfast. Particular advantages. Mrs. Parkes’s opinion. Time gained, how to be employed. 61—70 6 CONTENTS CHAPTER IV. KEEPING ACCOUNTS. Every housewife should keep her own accounts. Defi ciency in female instruction. Method of keeping an account. Advantages.............................................