Robert Burns and the Tradition of the Makars Robert L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burns's "To a Louse"; Scott's Old Mortality

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 17 | Issue 1 Article 18 1982 Notes and Documents: the Carlyle Centenary; Burns's "To a Louse"; Scott's Old Mortality Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation (1982) "Notes and Documents: the Carlyle Centenary; Burns's "To a Louse"; Scott's Old Mortality," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 17: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol17/iss1/18 This Notes/Documents is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND DOCUMENTS Thomas Carlyle in 1981 The Carlyle centenary of 1981 has been celebrated so various ly, and in so many parts of the world, that there seems little remaining doubt about CarlYle's importance. That he has re surfaced after decades of neglect or unpopularity, that his reputation has survived allegations of fascism, above all that critical interest has matured beyond squabblings about his private life to look at the man and his works, all contribute to a sense that one hundred years after his death, Thomas Carlyle can perhaps be seen more clearly as a Victorian of first rank. The repositories of Carlyle papers around the world did well to mount substantial exhibitions, at Duke, at Santa Cruz, in Edinburgh University and Public libraries as well as at the National Library of Scotland. Chelsea had a small but inter esting exhibition, and as these words are written the display in the National Portrait Gallery of London is attracting wide spread attention. -

TRAVEL and ADVENTURE in the WORKS of ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON by Mahmoud Mohamed Mahmoud Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department

TRAVEL AND ADVENTURE IN THE WORKS OF ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON by Mahmoud Mohamed Mahmoud Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Scottish Literature University of Glasgow. JULY 1984 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deepest sense of indebtedness and gratitude to my supervisor, Alexander Scott, Esq., whose wholehearted support, invaluable advice and encouragement, penetrating observations and constructive criticism throughout the research have made this work possible; and whose influence on my thinking has been so deep that the effects, certainly, will remain as long as I live. I wish also to record my thanks to my dear wife, Naha, for her encouragement and for sharing with me a considerable interest in Stevenson's works. Finally, my thanks go to both Dr. Ferdous Abdel Hameed and Dr. Mohamed A. Imam, Department of English Literature and Language, Faculty of Education, Assuit University, Egypt, for their encouragement. SUMMARY In this study I examine R.L. Stevenson as a writer of essays, poems, and books of travel as well as a writer of adventure fiction; taking the word "adventure" to include both outdoor and indoor adventure. Choosing to be remembered in his epitaph as the sailor and the hunter, Stevenson is regarded as the most interesting literary wanderer in Scottish literature and among the most intriguing in English literature. Dogged by ill- health, he travelled from "one of the vilest climates under heaven" to more congenial climates in England, the Continent, the States, and finally the South Seas where he died and was buried. Besides, Stevenson liked to escape, especially in his youth, from the respectabilities of Victorian Edinburgh and from family trouble, seeking people and places whose nature was congenial to his own Bohemian nature. -

An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf

Merge Volume 1 Article 2 2017 The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Tera Pate Follow this and additional works at: https://athenacommons.muw.edu/merge Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Tara. "The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf." Merge, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 1-17. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ATHENA COMMONS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Merge by an authorized editor of ATHENA COMMONS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Image Source: “Converged” by Phil Whitehouse is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Volume 1 Spring 2017 Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1 Spring, 2017 Managing Editor: Maddy Norgard Editors: Colin Damms Cassidy DeGreen Gabrielle Lestrade Faculty Advisor: Dr. Kim Whitehead Faculty Referees: Dr. Lisa Bailey Dr. April Coleman Dr. Nora Corrigan Dr. Jeffrey Courtright Dr. Sacha Dawkins Dr. Randell Foxworth Dr. Amber Handy Dr. Ghanshyam Heda Dr. Andrew Luccassan Dr. Bridget Pieschel Dr. Barry Smith Mr. Alex Stelioes – Wills Pate 1 Tera Katherine Pate The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Old English literature is the product of a country in religious flux. Beowulf and its women are creations of this religiously transformative time, and juxtapositions of this work’s women with the women of more Pagan and, alternatively, more Christian works reveals exactly how the roles of women were transforming alongside the shifting of religious belief. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars R.D.S

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 30 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-1998 Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars R.D.S. Jack Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jack, R.D.S. (1998) "Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 30: Iss. 1. Available at: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol30/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the USC Columbia at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R. D. S. Jack Which Vernacular Revival? Burns and the Makars When I was introduced to Bums at university, he was properly described as the senior member of a poetic trinity. With Ramsay and Fergusson, we were told, he initiated something called "The Vernacular Revival." That is, in the eighteenth century these poets revived poetic use of Scots ("THE vernacular") after a seventeenth century of treacherous anglicization caused by James VI and the Union of the Crowns. Sadly, as over a hundred years had elapsed, this worthy rescue effort might resuscitate but could never restore the national lan guage to the versatility in fullness of Middle Scots. This pattern and these words-national language, treachery, etc.-still dominate Scottish literary history. They are based on modem assumptions about language use within the United Kingdom. To see Bums's revival of the Scots vernacular in primarily political terms conveniently makes him anticipate the linguistic position of that self-confessed twentieth-century Anglophobe, C. -

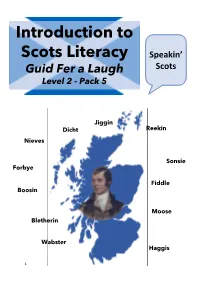

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution During Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting Packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scot Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scot Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, short bread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

A Caledonian Cacophony: Languages and Literatures of Scotland

A Caledonian Cacophony Languages and Literatures of Scotland Manfred Malzahn Department of English Literature United Arab Emirates University Al Ain, U.A.E. Biannual Conference: Sustainable Multilingualism Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania 26-27 May 2017 English Scots Gaelic UK Languages Mapping Twitter @UKLANGMAPPING https://twitter.com/uklangmapping/status/76112836220727705 6 Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) http://www.omniglot.com/writing/gaelic.htm Ceud mile fàilte. Ciamar a tha thu? Tha mi gu math, tapadh leat. Am bheil Gàidhlig agad? Tha an la fliuch an diugh. Tha am pathadh orm. Slàinte mhath! Bithidh mi a’ dol dhachaidh. Oidhche mhath. Scots (Lallans) http://www.scotslanguage.com Scots History Scots originated with the tongue of the Angles who arrived in Scotland about AD 600, or 1,400 years ago. During the Middle Ages this language developed and grew apart from its sister tongue in England, until a distinct Scots language had evolved. At one time Scots was the national language of Scotland, spoken by Scottish kings, and was used to write the official records of the country. Scots (Lallans) http://www.lallans.co.uk/ http://www.scots-online.org/ Hou’s aw wi ye? Hou’s yer dous? Hou d’ye fend? (SW) Hou ye lestin? (Borders) Whit fettle? (Borders) Whit like? (NE) Whit wey are ye? (Ulster) Whit aboot ye? (Ulster) Brawly—thank ye. No bad, conseederin. A canna compleen. Hingin by a threed. A hae been waur. “Toward a holistic national language policy for Scotland” Mark McConville, Scottish Language34 (2015) pp. 42-57 “Partly as a result of the introduction of obligatory English-medium schooling in 1872, language practices across Scotland were, until recently, characterised by a kind of diglossia, with English being used in high domains, and either Gaelic or Scots being used in low domains.” (45) The Ring of Words. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Allan Ramsay, ‘Verses by the Celebrated Allan Ramsay to his Son. On his Drawing a Fine Gentleman’s Picture’, in The Scarborough Miscellany for the Year 1732, 2nd edn (London: Wilford, 1734), pp. 20–22 (p. 20, p. 21, p. 21). 2. See Iain Gordon Brown, Poet & Painter, Allan Ramsay, Father and Son, 1684–1784 (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 1984). 3. When considering works produced prior to the formation of the United Kingdom in 1801, I have followed in this study the eighteenth-century prac- tice of using ‘united kingdom’ in lower case as a synonym for Great Britain. 4. See, respectively, Kurt Wittig, The Scottish Tradition in Literature (London: Oliver and Boyd, 1958); G. Gregory Smith, Scottish Literature: Character and Influence (London: Macmillan, 1919); Hugh MacDiarmid, A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, ed. by Kenneth Buthlay (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1988); David Craig, Scottish Literature and the Scottish People, 1680–1830 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1961); David Daiches, The Paradox of Scottish Culture: The Eighteenth-Century Experience (London: Oxford University Press, 1964); Kenneth Simpson, The Protean Scot: The Crisis of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Scottish Literature (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988); Robert Crawford, Devolving English Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992); Murray Pittock, Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth- Century Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) and idem, Scottish and Irish Romanticism (Oxford: Oxford University -

November 2020

‘The Vision’ The Robert Burns World Federation Newsletter Issue 47 November 2020 I have decided to give the newsletter the title of ‘The Vision’ as a nod to Burns’s poem of that name in which he bemoans the lack of recognition for poets from his native Ayrshire. His vision involves the appearance the muse Coila. However, the critic David Daiches remarked that ‘the poet does not quite know what to do with her when he brought her in.’ In composing this edition of the newsletter, I felt much the same as I didn’t know what I was going to do about the lack of copy which normally flows in unsolicited from around the world. Fortunately, my colleagues on the Board came up trumps and offered various leads for suitable material. It is a pleasure to report on a very successful Tamfest which explored Burns’s famous poem Tam o’ Shanter in great depth. The importance of music in relation to Burns also comes across strongly with a couple of articles highlighting his continuing influence on contemporary performers. Editor In this Issue: Page Halloween - Profile of President Marc Sherland 1-2 - A New Tartan for the Federation 2 Amang the bonie winding banks, - Lesley McDonald elected at President of LABC 2 Where Doon rins, wimpling, clear; - Tamfest 2020 3 - Simon Lamb Performance Poet 3 Where Bruce ance ruled the martial ranks, - Singer Lauren McQuistin 4-5 An’ shook his Carrick spear; - Heritage Item, Burns’s Mother’s Well 5 Some merry, friendly, country-folks - 200 Club 6 - New Burns Selection for Every Day 6 Together did convene, - St Andrew’s Day Lecture 6 To burns their nits, an’ pou their stocks, - Volunteers for Ellisland 7 An’ haud their Hallowe’en - Habbie Poetry Competition 8 - Federation Yule Concert 9 Fu’ blythe that night.