Thor's Return of the Giant Geirrod's Red-Hot Missile Seen in a Cosmic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 & 2 Samuel Series Lesson #176

1 & 2 Samuel Series Lesson #176 June 25, 2019 Dean Bible Ministries www.deanbibleministries.org Dr. Robert L. Dean, Jr. LEVIATHAN, TANNIN, AND RAHAV–PART 3 2 SAMUEL 7:18–29; PSALM 89:10 What the Bible Teaches About The Davidic Covenant Psa. 89:10, “You have broken Rahab in pieces, as one who is slain; You have scattered Your enemies with Your mighty arm.” comm masc sing abs Rahab, Rahav רהַב proper Rahab, literally, Rachav, name רָ חָב This term shows up in in Job 9:13; Job 26:12; Psalm 89:10; Isaiah 51:9. TWOT describes the verbal form in this manner: The basic meaning of the noun is arrogance. Rahav, can best be translated as “the arrogant one.” 1. God created all living things including Rahav, leviathan, behemoth, the sea, and the tannin. These are real, not mythological creatures and creation. 2. God in His omniscience designed all of these things. Their design was intentional, with a view to how they would be used as biblical symbols as well as mythological representations. Tracing these “sea monsters” 1. Yam 2. Tannin 3. Leviathan 4. Rahav 5. Behemoth GOD the Creator Mythological Deities All creatures: Yam, Leviathan, Behemoth, Tannin, Rahav designed with a purpose Uses God’s creatures to represent pagan deities [demons] and to describe origin myths. Referred to in the Bible: 1. As actual, historical creatures, and also 2. with a view to their mythological connotations to communicate God vs. evil. Job 9:13, “God will not turn back His anger; Beneath Him crouch the helpers of Rahav.” [NKJV: allies of the proud] Isa. -

Old Norse Mythology — Comparative Perspectives Old Norse Mythology— Comparative Perspectives

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No. 3 OLd NOrse MythOLOgy — COMParative PersPeCtives OLd NOrse MythOLOgy— COMParative PersPeCtives edited by Pernille hermann, stephen a. Mitchell, and Jens Peter schjødt with amber J. rose Published by THE MILMAN PARRY COLLECTION OF ORAL LITERATURE Harvard University Distributed by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2017 Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives Published by The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England Copyright © 2017 The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature All rights reserved The Ilex Foundation (ilexfoundation.org) and the Center for Hellenic Studies (chs.harvard.edu) provided generous fnancial and production support for the publication of this book. Editorial Team of the Milman Parry Collection Managing Editors: Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy Executive Editors: Casey Dué and David Elmer Production Team of the Center for Hellenic Studies Production Manager for Publications: Jill Curry Robbins Web Producer: Noel Spencer Cover Design: Joni Godlove Production: Kristin Murphy Romano Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hermann, Pernille, editor. Title: Old Norse mythology--comparative perspectives / edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, with Amber J. Rose. Description: Cambridge, MA : Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, 2017. | Series: Publications of the Milman Parry collection of oral literature ; no. 3 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017030125 | ISBN 9780674975699 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mythology, Norse. | Scandinavia--Religion--History. Classifcation: LCC BL860 .O55 2017 | DDC 293/.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030125 Table of Contents Series Foreword ................................................... -

An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf

Merge Volume 1 Article 2 2017 The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Tera Pate Follow this and additional works at: https://athenacommons.muw.edu/merge Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Tara. "The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf." Merge, vol. 1, 2017, pp. 1-17. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ATHENA COMMONS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Merge by an authorized editor of ATHENA COMMONS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Image Source: “Converged” by Phil Whitehouse is licensed under CC BY 2.0 Volume 1 Spring 2017 Merge: The W’s Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1 Spring, 2017 Managing Editor: Maddy Norgard Editors: Colin Damms Cassidy DeGreen Gabrielle Lestrade Faculty Advisor: Dr. Kim Whitehead Faculty Referees: Dr. Lisa Bailey Dr. April Coleman Dr. Nora Corrigan Dr. Jeffrey Courtright Dr. Sacha Dawkins Dr. Randell Foxworth Dr. Amber Handy Dr. Ghanshyam Heda Dr. Andrew Luccassan Dr. Bridget Pieschel Dr. Barry Smith Mr. Alex Stelioes – Wills Pate 1 Tera Katherine Pate The Pagan and the Christian Queen: An Examination of the Role of Wealhtheow in Beowulf Old English literature is the product of a country in religious flux. Beowulf and its women are creations of this religiously transformative time, and juxtapositions of this work’s women with the women of more Pagan and, alternatively, more Christian works reveals exactly how the roles of women were transforming alongside the shifting of religious belief. -

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 a Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola

From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1 A Study in the Longue Durée Wikander, Ola Published in: Studies in Isaiah 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wikander, O. (2017). From Indo-European Dragon Slaying to Isa 27.1: A Study in the Longue Durée. In T. Wasserman, G. Andersson, & D. Willgren (Eds.), Studies in Isaiah: History, Theology and Reception (pp. 116- 135). (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, 654 ; Vol. 654). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 LIBRARY OF HEBREW BIBLE/ OLD TESTAMENT STUDIES 654 Formerly Journal of the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series Editors Claudia V. -

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

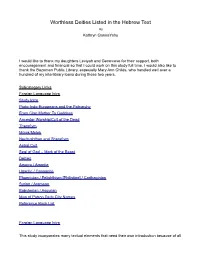

Worthless Deities in the Hebrew Text

Worthless Deities Listed in the Hebrew Text by Kathryn QannaYahu I would like to thank my daughters Leviyah and Genevieve for their support, both encouragement and financial so that I could work on this study full time. I would also like to thank the Bozeman Public Library, especially Mary Ann Childs, who handled well over a hundred of my interlibrary loans during these two years. Subcategory Links Foreign Language Intro Study Intro Proto-Indo-Europeans and the Patriarchy From Clan Mother To Goddess Ancestor Worship/Cult of the Dead Therafiym Molek/Melek Nechushthan and Sherafiym Astral Cult Seal of God – Mark of the Beast Deities Amurru / Amorite Ugaritic / Canaanite Phoenician / Felishthiym [Philistine] / Carthaginian Syrian / Aramean Babylonian / Assyrian Map of Patron Deity City Names Reference Book List Foreign Language Intro This study incorporates many textual elements that need their own introduction because of all the languages presented. For the Hebrew, I use a Hebrew font that you will not be able to view without a download, unless you happen to have the font from another program. If you should see odd letters strung together where a name or word is being explained, you probably need the font. It is provided on my fonts page http://www.lebtahor.com/Resources/fonts.htm . Since Hebrew does not have an upper and lower case, another font used for the English quoting of the Tanak/Bible is the copperplate, which does not have a case. I use this font when quoting portions of the Tanak [Hebrew Bible], to avoid translator emphasis that capitalizing puts a slant on. -

Herjans Dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age

Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Félagsvísindasvið Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Femininities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age Luke John Murphy Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Gunnell Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands 2013 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni Trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Luke John Murphy, 2013 Reykjavík, Ísland 2013 Luke John Murphy MA in Old Nordic Religions: Thesis Kennitala: 090187-2019 Spring 2013 ABSTRACT Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age This thesis is a study of the valkyrjur (‘valkyries’) during the late Iron Age, specifically of the various uses to which the myths of these beings were put by the hall-based warrior elite of the society which created and propagated these religious phenomena. It seeks to establish the relationship of the various valkyrja reflexes of the culture under study with other supernatural females (particularly the dísir) through the close and careful examination of primary source material, thereby proposing a new model of base supernatural femininity for the late Iron Age. The study then goes on to examine how the valkyrjur themselves deviate from this ground state, interrogating various aspects and features associated with them in skaldic, Eddic, prose and iconographic source material as seen through the lens of the hall-based warrior elite, before presenting a new understanding of valkyrja phenomena in this social context: that valkyrjur were used as instruments to propagate the pre-existing social structures of the culture that created and maintained them throughout the late Iron Age. -

An Example Reinterpreting the British Isles' Most Detailed Account of a Sea Serpent Sight

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ethnobiology and Conservation 2019, 8:12 (12 October 2019) doi:10.15451/ec2019-10-8.12-1-31 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com Ethnobiology and Shifting Baselines: An Example Reinterpreting the British Isles’ Most Detailed Account of a Sea Serpent Sighting as Early Evidence for PrePlastic Entanglement of Basking Sharks Robert L. France ABSTRACT Recognizing shifts in baseline conditions is necessary for understanding longterm changes in populations as a prelude to implementing presentday management actions and setting future restoration goals for anthropogenicallyaltered marine ecosystems. Examining historical information contained within anecdotal accounts from nontraditional sources has previously proven useful in this regard. Herein, I scrutinize eyewitness accounts and accompanying illustrations published in nineteenthcentury natural history journals which together comprise the most detailed description of sighting a purported sea serpent in the British Isles. I then reinterpret this anecdote (as well as complementary evidence offered by cryptozooloogists in its support obtained from other published journal articles of similarly described unidentified marine objects), suggesting it to provide one of the earliest reports of the nonlethal entanglement of an animal—in this case what I believe to have been a basking shark—in European waters. The present work suggests that the entanglement of sharks in fishing gear or hunting equipment has a much longer environmental history than is commonly believed, and provides another example of how ethnozoological studies can contribute toward recognizing past fishingrelated pressures and baseline shifts in affected populations. Sharks, it seems, have been subjected to the impacts of not just direct fishery exploitation but also through becoming bycatch, long before the advent and widespread use of plastic in the middle of the twentieth century. -

A Traditional Story Many Myths, Legends, and Traditional Stories from Around the World Are About Such Things As Fire, Water, Rain, Wind, Or Thunder and Lightning

✩ A traditional story Many myths, legends, and traditional stories from around the world are about such things as fire, water, rain, wind, or thunder and lightning. Sometimes these things take the form of giants, gods, or spirits that can harm or help humans. Carefully read the following facts about Norse gods. Thor and Sif What Thor was like Thor was an exaggerated, colorful character. He was huge, even for a god, and incredibly strong. He had wild hair and beard and a temper to match. He was never angry for long, though, and easily forgave people. Thor raced across the sky in his chariot drawn by two giant goats, Toothgnasher and Toothgrinder. It was their hooves that people heard when it thundered on Earth. He controlled the thunder and lightning and brewed up storms by blowing through his beard. Sailors prayed to him for protection from bad weather. Thor’s magic weapons Thor had a belt which doubled his strength when he buckled it on and iron gauntlets which allowed him to grasp any weapon. The most famous of Thor’s weapons was his hammer, Mjollnir. It always hit its target and returned to Thor’s hands after use. When a thunderbolt struck Earth, people said that Thor had flung down his hammer. Mjollnir did not only do harm, though. It also had protective powers and people wore small copies of it as jewellery to keep them safe and bring good luck. Sif Thor was married to Sif, who was famous for her pure gold, flowing hair. She was a goddess of fruitfulness and plenty. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes.