200701-2007 Terrafugia Transition Aerocar Concept.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1954 Aerocar One

1954 Aerocar One Aerocar International's Aerocar (often called the Taylor Aerocar ) was an American roadable aircraft, designed and built by Moulton Taylor in Longview, Washington, in 1949. Although six examples were built, the Aerocar never entered production. Design and development Taylor's design of a roadable aircraft dates back to 1946. During a trip to Delaware, he met inventor Robert E. Fulton, Jr., who had designed an earlier roadable airplane, the Aerophobia. Taylor recognized that the detachable wings of Fulton’s design would be better replaced by folding wings. His prototype Aerocar utilized folding wings that allowed the road vehicle to be converted into flight mode in five minutes by one person. When the rear license plate was flipped up, the operator could connect the propeller shaft and attach a pusher propeller. The same engine drove the front wheels through a three-speed manual transmission. When operated as an aircraft, the road transmission was simply left in neutral (though backing up during taxiing was possible by the using the reverse gear.) On the road, the wings and tail unit were designed to be towed behind the vehicle. Aerocars could drive up to 60 miles per hour and have a top airspeed of 110 miles per hour. Testing and certification Civil certification was gained in 1956 under the auspices of the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), and Taylor reached a deal with Ling-Temco-Vought for serial production on the proviso that he was able to attract 500 orders. When he was able to find only half that number of buyers, plans for production ended, and only six examples were built, with one still flying as of 2008 and another rebuilt by Taylor into the only Aerocar III. -

FLYING CARS / ROADABLE AIRPLANES AUGUST 2012 Please Send Updates and Comments to Tom Teel: [email protected] Terrafugia

FLYING CARS / ROADABLE AIRPLANES AUGUST 2012 Please send updates and comments to Tom Teel: [email protected] Terrafugia INTERNATIONAL FLYING CAR ASSOCIATION http://www.flyingcarassociation.com We'd like to welcome you to the International Flying Car Association. Our goal is to help advance the emerging flying car industry by creating a central resource for information and communication between those involved in the industry, news networks, governments, and those seeking further information worldwide. The flying car industry is in its formative stages, and so is IFCA. Until this site is fully completed, we'd like to recommend you visit one of these IFCA Accredited Sites. www.flyingcars.com www.flyingcarreviews.com www.flyingcarnews.com www.flyingcarforums.com REFERENCE INFORMATION Roadable Times http://www.roadabletimes.com Transformer - Coming to a Theater Near You? http://www.aviationweek.com/Blogs.aspx?plckBlo PARAJET AUTOMOTIVE - SKYCAR gId=Blog:a68cb417-3364-4fbf-a9dd- http://www.parajetautomotive.com/ 4feda680ec9c&plckController=Blog&plckBlogPage= In January 2009 the Parajet Skycar expedition BlogViewPost&newspaperUserId=a68cb417-3364- team, led by former British army officer Neil 4fbf-a9dd- Laughton and Skycar inventor Gilo Cardozo 4feda680ec9c&plckPostId=Blog%253aa68cb417- successfully completed its inaugural flight, an 3364-4fbf-a9dd- incredible journey from the picturesque 4feda680ec9cPost%253a6b784c89-7017-46e5- surroundings of London to Tombouctou. 80f9- Supported by an experienced team of overland 41a312539180&plckScript=blogScript&plckElement -

The the Roadable Aircraft Story

www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Table of Contents What Next, Slide/s Part Description Flying Cars? 1N/ATitle 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~53 1 The Holy Grail 54~101 2 Learning to Fly The 102~155 3 The Challenge 156~194 4 Two Types Roadable 195~317 5 One Way or Another 318~427 6 Between the Wars Aircraft 428~456 7 The War Years 457~572 8 Post-War Story 573~636 9 Back to the Future 1 637~750 10 Next Generation 2 Part 1 Exceeding the Grasp The Holy Grail 3 4 “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven f?for? Robert Browning, Poet Above: caption: “The Cars of Tomorrow - 1958 Pontiac” Left: a “Flying Auto,” as featured on the 5 cover of Mechanics and Handi- 6 craft magazine, January 1937 © J.M. Syken 1 www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Above: for decades, people have dreamed of flying cars. This con- ceptual design appeared in a ca. 1950s issue of Popular Mechanics The Future That Never Was magazine Left: cover of the Dec. 1947 issue of the French magazine Sciences et Techniques Pour Tous featur- ing GM’s “RocAtomic” Hovercar: “Powered by atomic energy, this vehicle has no wheels and floats a few centimeters above the road.” Designers of flying cars borrowed freely from this image; from 7 the giant nacelles and tail 8 fins to the bubble canopy. Tekhnika Molodezhi (“Tech- nology for the Youth”) is a Russian monthly science ma- gazine that’s been published since 1933. -

Ano Desenvolvedor Modelos Status Motivo Foto 1917 Glenn Curtiss Curtiss Autoplane Falha Projeto Deixado De Lado Devido a 1ª

Ano Desenvolvedor Modelos Status Motivo Foto Projeto deixado Curtiss de lado devido a 1917 Glenn Curtiss Falha Autoplane 1ª Guerra Mundial Modo 1921 Rene Tampier Roadable Falha carro/avião não automatizado. Raúl Pateras Carro- Não há registros 1922 Falha Pescaras Cóptero de protótipos. Waldo Waterman 1937 - - Waterman Arrowbile Dixon Sem registro de 1940 Jess Dixon Falha Flying Car voo. Consumo excessivo de Governo Hafner 1944 Falha combustível e Britânico Rotabuggy operação complicada. Falta de 1945 Robert Fulton Airphibian Falha investidores. Acidente de voo Ted Hall que matou o 1947 ConvAirCar Falha Convair piloto e projetista. Taylor Existem versões 1949 Moulton Taylor Aerocar, Sucesso melhoradas. s200 Morte do 1953 Leland D. Bryan Autoplane Falha projetista em um voo de teste. Altura máxima 1957 David Dobbins Simcopter Falha do solo de 1,5m Grupo União Desenvolvido do - Européia Mycopter Conceito projeto conceito. (Concórscio) Eficiência menor Piasecki que um Piasecki 1957 VZ-8 Falha helicóptero no Helicopter Airgeep transporte de pessoas. Curtiss- 1958 Curtiss-Wright Wright VZ- Falha - 7 Carro Modelo Roy L. Clough, 1962 Voador do Conceito detalhado em Jr Futuro escala reduzida Sky - Aircar - Protótipo Technologies Henry Smolinski Morte dos 1971 AVE(Advanced AVE Mizar Falha projetistas em Vehicle voo teste. Engineers) Incapaz de 1974 Avro Aircraft Avrocar Falha alcançar os objetivos Está à venda Arlington Sky 1980 Protótipo protótipo deste Washington Commuter modelo. G150, Sem previsão G412, para o 1996 Gizio Conceito G440 e lançamento do G450 protótipo. Skycar Aguardando - Parajet Expedition, Sucesso liberação para SkyRunner produção. SkyRider - Macro/Alabama - Projeto X2R Moller Existem vários M100, protótipos em Moller 2002 M200G e Desenvolvimento teste, porém International M400 sem previsão de Skycar lançamento. -

Waldo Waterman Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10154

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8w95fs8 No online items The Descriptive Finding Guide for the Waldo Waterman Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10154 AR San Diego Air and Space Museum Library and Archives 6/2016 2001 Pan American Plaza, Balboa Park San Diego 92101 URL: http://www.sandiegoairandspace.org/ The Descriptive Finding Guide for SDASM.SC.10154 1 the Waldo Waterman Personal Papers SDASM.SC.10154 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: San Diego Air and Space Museum Library and Archives Title: Waldo Waterman Personal Papers Identifier/Call Number: SDASM.SC.10154 Physical Description: .4 Cubic FeetThe collection of Waldo Waterman includes newspaper articles, magazine articles, manuscripts, photographs, blueprints and correspondence regarding his invention of the Aeroplane. The collection includes original blueprints, correspondence with patent offices and other people who were interested in his invention. There are several manuscripts of books written by Waterman and several magazine articles were written about him. There are two boxes in this collection due to the oversized documents that needed to be stored.2 archival boxes Date (bulk): bulk Abstract: Waldo Dean Waterman an aviation pioneer from San Diego, California. Biographical / Historical Waldo Dean Waterman an aviation pioneer from San Diego, California. He was born on June 16, 1894 in San Diego, CA. He was an inventor of many types of aircraft and engines. His most notable contribution to aviation was the first tailless monoplanes, the first aircraft with modern tricycles landing gear and the first successful low cost and simple to fly. It was resembled a flying car and was commonly called a Flivver Aircraft. -

Vehículos Híbridos Que Vuelan Y Ruedan (I) UNITED STATES Coches Voladores

EUROPE LATAM MIDDLE EAST Vehículos híbridos que vuelan y ruedan (I) UNITED STATES www.aertecsolutions.com Coches voladores Los coches voladores en el cine: Blade Runner, 1910 I Guerra Mundial 1920 1930 II Guerra Mundial 1940 1950 1960 (1914-1918) (1939-1945) Volver al futuro o El Quinto Elemento Jess Dixon's Flying Automobile Aerauto PL.5C Autoplane Ercoupe Autoplane Bryan Autoplane Curtiss Autoplane Tampier Roadable Biplane Windmill Autoplane Jess Dixon’s Flying Aerauto PL.5C Autoplane Ercoupe Autoplane Curtiss-Wright VZ-7 D-Hagu 1958 1917 –Glenn Curtiss 1921 –René Tampier 1935 –Edward A. Stalker 1940 Automobile 1949 –Luigi Pellarini 1950 –James W. Holland –Curtiss-Wright 1965 (The Wagner Aerocar) Se presentó en la Exposición Presentado en el Paris Air Show Fue el primer intento de un coche –Jess Dixon Pensado para un piloto y un De fuselaje monoplano, plegaba Vehículo fabricado para el ejército –Alfred Vogt Aeronáutica Panamericana de de 1921 (Le Bourget), fue probado volador tipo autogiro. Monocóptero pensado para los pasajero, utilizaba la propulsión de las alas para andar por carretera. de los EE.UU., diseñado para Un helicóptero algo peculiar, el Nueva York y fue el primer coche con éxito e impresionó a la problemas de tráfico en la ciudad. las hélices también para moverse Al no cumplir las normas de actuar como "jeep de vuelo". Con D-Hagu fue diseñado a partir del que llegó a volar realmente. multitud. Las alas se doblaban Autogiro AC-35 Autoplane Era un vehículo pequeño para por la carretera, lo que lo convertía seguridad vial de EE.UU., su cuatro hélices (un par a cada lado rotocar III y el helicóptero Sky-Trac La cabina era de aluminio, motor hacia atrás y se accionaba un 1936 –Autogiro Company of America transportar sólo al piloto. -

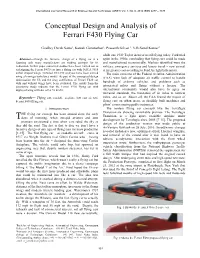

Conceptual Design and Analysis of Ferrari F430 Flying Car

International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology (IJRET) Vol. 1, No. 6, 2012 ISSN 2277 – 4378 Conceptual Design and Analysis of Ferrari F430 Flying Car Godfrey Derek Sams1, Kamali Gurunathan1, Prasanth Selvan 1, V.R.Sanal Kumar2 while one 1949 Taylor Aerocar is still flying today. Ford tried Abstract—Though the lucrative design of a flying car is a again in the 1950s, concluding that flying cars could be made daunting task many manufactures are making attempts for its and manufactured economically. Markets identified were the realization. In this paper numerical studies have been carried out to military, emergency services and luxury travel – now served, redesigning the Ferrari F430 car into a flying car with NACA 9618 at far greater cost according to Ford, by light helicopters. airfoil shaped wings. Detailed 3D CFD analyses have been carried The main concerns of the Federal Aviation Administration using a k-omega turbulence model. As part of the conceptual design (FAA) were lack of adequate air traffic control to handle optimization the lift and the drag coefficients of Ferrari F430 car with and without wings have been evaluated. The results from the hundreds of airborne vehicles, and problems such as parametric study indicate that the Ferrari F430 flying car with intoxicated pilots and flying without a license. The deployed wing will take off at 53 km/hr. international community would also have to agree on universal standards, the translation of air miles to nautical Keywords— Flying car, roadable airplane, low cost air taxi, miles, and so on. Above all, the FAA feared the impact of Ferrari F430 flying car. -

We All Fly: General Aviation and the Relevance of Flight Exhibition Theme

We All Fly: General Aviation and the Relevance of Flight Exhibition Theme: General aviation flight is everywhere and affects everyone, whether you fly or not. Exhibition Abstract: What is General Aviation? General aviation is all non‐scheduled civilian and non‐military flight and it is woven into the fabric of modern life. As a result, general aviation provides employment, services and transportation for people, companies, and communities around the world. All aviation was “general” until military and scheduled commercial segments were established. Today, nearly 80% of civil aircraft in the United States operated in a segment of general aviation. General aviation accounts for three out of four flight operations in the United States and the U.S. accounts for over half of all general aviation activity in the world. The freedom to fly in the U.S. is like nowhere else on earth. Personal flying accounts for more than a third of all general aviation hours flown. Corporate and business flying accounts for nearly a quarter, and instructional flying almost a fifth. In 2013, nearly 200,000 general aviation aircraft logged 22.9 million flight hours in the U.S. Aside from the movement of people and cargo, general aviation has a surprising economic impact on local airports and communities and in national and global arenas. General aviation is the training ground for our next generation of pilots and, like any industry, offers multidisciplinary employment opportunities. In the larger cultural and social context, general aviation provided the only opportunity, often hard‐fought, for many to participate in aviation. It served as the proving grounds for women and minorities who then entered all aspects of aerospace when the civil rights and women’s movements finally pushed aside legal and social barriers. -

Samson Switchblade the Flying Car

Samson Switchblade THE Flying Car presented by Jerry Clark EAA 555 Las Cruces 19 November 2019 The Flying Car No more gridlock! But where are the wings? Jules Vern’s 1904 flying boat, car, airplane 1937 Waterman Airrowbile (detachable) 1938 PreWar Car (detachable) 1946 Fulton Airphibian 1947 ConvAirCar 1949 Moulton Taylor Aerocar III (First complete) 6 produced 1949 Moulton Taylor Aerocar III 1949 Moulton Taylor Aerocar III Still struggling with that wing thing! • The Personal Air Vehicle Exploration (PAVE) program at NASA's Langley Research Center developed easy-to-use aircraft that may • • • Take you from your garage to the airport and on to your destination, saving time - and dollars • • "That's always been the dream," said Andrew Hahn, PAVE analyst at Langley, of flying cars. "Our plan is to have a flying demonstrator by [2009]" 2003 NASA PAV Design • Seats: > 5 Goals • • 150–200 mph cruising speed • • Able to be flown by anyone with a driver’s license* • • As affordable as travel by car or airliner • • Near all-weather capability enabled by synthetic vision systems • • Highly fuel efficient 800 miles (1,300 km) range • • • Provide "door-to-door" transportation solutions, through use of small community airports that are in close proximity to 2008 PAVE Tail Fan (aircraft) 2003 NASA PAVE (Small Aircraft Transportation system) • The TailFan tackled some of the biggest challenges to personal air vehicles. • Ease-of-use, new propulsion, cheaper build • • environmental issues like noise and pollution, as well as affordability. • New technologies • ADHARS 2008 PAV DARPA • DARPAs able to fly for 2 hours • Carry 2 to 4 • 8.5 feet wide and less than 24 feet • No higher than 7 feet when in the road configuration • Drive at up to 60 MPH or fly at up to 150 MPH. -

Flying Blind- Cars That Take to the Air Are Here, but What Are The

CARS THAT CAN TAKE TO THE AIR ARE HERE, BUT WHAT ARE THE INSURANCE AND CLAIMS IMPLICATIONS? BY ANDREW L. SMITH FlyingAND BRIAN P. HENRY Blind28 CLM MAGAZINE JANUARY 2018 Fifty-five years ago, the cartoon “The according to my Apple Watch it is not yet secure a fully functional flying car by the Jetsons” introduced a space-age family 2062, but flying cars are here. end of 2018, if not earlier. complete with George, Jane, Judy, Elroy, a The transition from drones to dog named Astro, and, last but not least, flying cars is only natural and is already AVAILABLE OPTIONS a robot maid named Rosie. The family well-underway. Police in Dubai, for Terrafugia, the first flying car lived in Orbit City in the year 2062 and example, are already using a HoverSurf manufacturer, is now beginning to sell “the its mode of transportation was none manufactured drone/motorcycle hybrid Transition,” which was initially developed other than a bubble-shaped flying saucer to fly around human police officers. So if in 2006. According to the company’s called an Aerocar. you are in the market for a flying car and website, “The Transition is the world’s In 1940, Henry Ford declared, you have a rather large bank account at first practical flying car. A folding-wing, “Mark my words: A combination your disposal, you’re in luck: Nineteen two-seat, roadable aircraft, the Transition airplane and motorcar is coming. You different companies are currently is designed to fly like a typical Light Sport may smile, but it will come.” Well, developing flying car products. -

Are We Ready to Drive to the Sky?: Personal Air-Land Vehicles Within

A thesis submitted to McGill Oleksiy Burchevskyy University in partial fulfillment Student # 260282254 of the requirements of the Faculty of Law degree of Master of Laws McGill University Montreal Are We Ready to Drive to the Sky? : Personal Air-Land Vehicles within the Modern Air Law Framework and Theory of Legal Innovation. LL.M. Thesis Advisor: Prof. Nicholas Kasirer Faculty of Law, McGill University December 2008 Copyright © 2008 Oleksiy Burchevskyy 1 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON MAOISM OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53606-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53606-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

„Wie Fühlt Sich Ein Fliegendes Auto An?“ Von Der Technologischen Vision Zur Benutzerfreundlichen Steuerung

Vom Reiz der Sinne: Wahrnehmung und Gehirn „Wie fühlt sich ein fliegendes Auto an?“ Von der technologischen Vision zur benutzerfreundlichen Steuerung Prof. Dr. Heinrich H. Bülthoff Max-Planck-Institut für biologische Kybernetik Abteilung: Wahrnehmung, Kognition und Handlung Der Traum vom fliegenden Auto ist nicht neu Verschiedene fliegende Autos wurden schon konzipiert. Aber bisher waren es nur Prototypen und vom Massenmarkt noch weit entfernt. ConVairAir, 1940s Taylor Aerocar, 1950s American Historical Society, 1945 29.5.2018 Max-Planck-Institut für biologische Kybernetik | Prof. Heinrich H. Bülthoff | Abteilung: Wahrnehmung, Kognition und Handlung 2 Neuere Entwicklungen (2000 – 2006) • Die Technologie für den Individualverkehr in der Luft existiert schon. • Nachteile der meisten Konzepte: • nicht für jedermann (Pilotenschein erforderlich) • Kompromisslösungen zwischen Auto und Flugzeug • benötigt Infrastruktur (Flugplatz und Straße) PAL-V International B.V., The Netherlands Transition, Terrafugia, USA 29.5.2018 Max-Planck-Institut für biologische Kybernetik | Prof. Heinrich H. Bülthoff | Abteilung: Wahrnehmung, Kognition und Handlung 3 Studie der EU: Individualverkehr in der Zukunft European Commission, Out of the box ̶ Ideas about the future of air transport, 2007 29.5.2018 Max-Planck-Institut für biologische Kybernetik | Prof. Heinrich H. Bülthoff | Abteilung: Wahrnehmung, Kognition und Handlung 4 Herausforderungen für Personal Aviation “Ein PAV zu entwickeln ist nur ein Bruchteil der bevorstehenden Herausforderungen… Die anderen Herausforderungen bestehen nach wie vor…” [EC, 2007] • Wie viele PAVs tolerieren wir? • Wer darf/kann fliegen? • Wie steht’s mit der Sicherheit und dem Lärm,… ? • Wie werden PAVs in das existierende Transportsystem integriert? European Commission, Out of the box ̶ Ideas about the future of air transport, 2007 29.5.2018 Max-Planck-Institut für biologische Kybernetik | Prof.