By Arthur Hill Chronicle Science Editor 1965-1974 Editor's Note: a Half

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

2021 Transpacific Yacht Race Event Program

TRANSPACTHE FIFTY-FIRST RACE FROM LOS ANGELES 2021 TO HONOLULU 2 0 21 JULY 13-30, 2021 Comanche: © Sharon Green / Ultimate Sailing COMANCHE Taxi Dancer: © Ronnie Simpson / Ultimate Sailing • Hamachi: © Team Hamachi HAMACHI 2019 FIRST TO FINISH Official race guide - $5.00 2019 OVERALL CORRECTED TIME WINNER P: 808.845.6465 [email protected] F: 808.841.6610 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF THE 51ST TRANSPACIFIC YACHT RACE The Transpac 2021 Official Race Handbook is published for the Honolulu Committee of the Transpacific Yacht Club by Roth Communications, 2040 Alewa Drive, Honolulu, HI 96817 USA (808) 595-4124 [email protected] Publisher .............................................Michael J. Roth Roth Communications Editor .............................................. Ray Pendleton, Kim Ickler Contributing Writers .................... Dobbs Davis, Stan Honey, Ray Pendleton Contributing Photographers ...... Sharon Green/ultimatesailingcom, Ronnie Simpson/ultimatesailing.com, Todd Rasmussen, Betsy Crowfoot Senescu/ultimatesailing.com, Walter Cooper/ ultimatesailing.com, Lauren Easley - Leialoha Creative, Joyce Riley, Geri Conser, Emma Deardorff, Rachel Rosales, Phil Uhl, David Livingston, Pam Davis, Brian Farr Designer ........................................ Leslie Johnson Design On the Cover: CONTENTS Taxi Dancer R/P 70 Yabsley/Compton 2019 1st Div. 2 Sleds ET: 8:06:43:22 CT: 08:23:09:26 Schedule of Events . 3 Photo: Ronnie Simpson / ultimatesailing.com Welcome from the Governor of Hawaii . 8 Inset left: Welcome from the Mayor of Honolulu . 9 Comanche Verdier/VPLP 100 Jim Cooney & Samantha Grant Welcome from the Mayor of Long Beach . 9 2019 Barndoor Winner - First to Finish Overall: ET: 5:11:14:05 Welcome from the Transpacific Yacht Club Commodore . 10 Photo: Sharon Green / ultimatesailingcom Welcome from the Honolulu Committee Chair . 10 Inset right: Welcome from the Sponsoring Yacht Clubs . -

Forever Remembered

July 2015 Vol. 2 No. 7 National Aeronautics and Space Administration KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S magazine FOREVER REMEMBERED Earth Solar Aeronautics Mars Technology Right ISS System & Research Now Beyond NASA’S National Aeronautics and Space Administration LAUNCH KENNEDY SPACE CENTER’S SCHEDULE SPACEPORT MAGAZINE Date: July 3, 12:55 a.m. EDT Mission: Progress 60P Cargo Craft CONTENTS Description: In early July, the Progress 60P resupply vehicle — 4 �������������������Solemn shuttle exhibit shares enduring lessons an automated, unpiloted version of the Soyuz spacecraft that is used to ����������������Flyby will provide best ever view of Pluto 10 bring supplies and fuel — launches 14 ����������������New Horizons spacecraft hones in on Pluto to the International Space Station. http://go.nasa.gov/1HUAYbO 24 ����������������Firing Room 4 used for RESOLVE mission simulation Date: July 22, 5:02 p.m. EDT 28 ����������������SpaceX, NASA will rebound from CRS-7 loss Mission: Expedition 44 Launch to 29 ����������������Backup docking adapter to replace lost IDA-1 the ISS Description: In late July, Kjell SHUN FUJIMURA 31 ����������������Thermal Protection System Facility keeping up Lindgren of NASA, Kimiya Yui of JAXA and Oleg Kononenko of am an education specialist in the Education Projects and 35 ����������������New crew access tower takes shape at Cape Roscosmos launch aboard a Soyuz I Youth Engagement Office. I work to inspire students to pursue science, technology, engineering, mathematics, or 36 ����������������Innovative thinking converts repair site into garden spacecraft from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan to the STEM, careers and with teachers to better integrate STEM 38 ����������������Proposals in for new class of launch services space station. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Obituaries, A

OBITUARIES, A - K Updated 7/31/2020 Bernardsville Library Local History Room NAME TITLE DATE OF DEATH SOURCE EDITION PAGE AGE NOTES NJ Archives Abstract & Aaron, Robert 01/13/1802 Wills Vol.X 1801-1805 7 Abantanzo, Marie 01/13/1923 Bernardsville News 01/18/1923 4 Abbate, Michael 06/22/1955 Bernardsville News 06/23/1955 1 Abberman, Jay 04/10/2005 Bernardsville News 04/14/2005 10 82 Abbey, E. Mrs. 06/02/1957 Bernardsville News 06/06/1957 4 Abbond, Doris Weakley 03/27/2000 Bernardsville News 03/30/2000 10 80 Abbond, Robert R. 02/09/1995 Bernardsville News 02/15/1995 10 82 Abbondanzo, Delores L. 11/03/2001 Bernardsville News 11/08/2001 11 75 Abbondanzo, Francis J. 12/26/1993 Bernardsville News 12/29/1993 10 69 Abbondanzo, L. Mrs. 12/22/1962 Bernardsville News 01/03/1963 2 Abbondanzo, Lena I. 05/08/2003 Bernardsville News 05/15/2003 10 80 Abbondanzo, Louis 12/23/1979 Bernardsville News 01/03/1980 6 89 Abbondanzo, Louis J. 12/25/1993 Bernardsville News 12/29/1993 10 65 Abbondanzo, Mary G. 06/12/2014 Bernardsville News 06/26/2014 8 88 Abbondanzo, Patricia A. 11/21/1983 Bernardsville News 11/24/1983 Abbondanzo, Patrick J. 12/11/2000 Bernardsville News 12/14/2000 10 78 Abbondanzo, Rose 12/22/1962 Bernardsville News 01/03/1963 2 63 Abbondanzo, Sharon J. 08/28/2013 Bernardsville News 09/05/2013 9 78 Abbondanzo, Vincent J. 07/26/1996 Bernardsville News 07/31/1996 10 66 Abbott, Charles Cortez Jr. -

Kennedy Space Center

July 12, 2002 Vol. 41, No. 14 Spaceport News America’s gateway to the universe. Leading the world in preparing and launching missions to Earth and beyond. http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/snews/snewstoc.htm John F. Kennedy Space Center Inside Kennedy Space Center Page 2 – The Germans led during the early days of the 40 years as NASA Center space program. Page 3 – Pioneers helped shape KSC’s manned and LOC began unmanned space programs. Remembering Our Heritage Page 4 –KSC facilities feature July 1, 1962 innovative designs. As the Kennedy Space Center Page 5 – Uses of rocket team begins a yearlong celebration technology continue to evolve. of our 40th year as a NASA center, Page 6 – Center generates it benefits us all to take a look back numerous spaceport and range at the beginnings of KSC. technology spinoffs. Only if we know where we came Page 7 – KSC becomes from will we understand where we Spaceport Technology Center. are as a launch center and Space- port Technology Center and how Page 8 – Astronauts maintain ties to KSC. we better can help propel NASA’s mission: “To improve life here. To Page 9 – Presidents, kings and extend life to there. To find life celebrities visit Center. beyond.” By listening to those who took Page 10 – Public affairs assists media in sharing the story, us to the Moon, we can learn just how far we can go if we put our Page 11 – History of KSC hearts and souls and minds to it. continues to be recorded; Histories written, being written. -

Matthew Hurtgen's Study of Sulfur Cycling in the Neoproterozoic

Greetings from Locy Hall, home of following projects: Matthew Hurtgen’s study of sulfur cycling in the NU’s Department of Earth and Plane- Neoproterozoic, Steven Jacobsen’s acquisition of a broadband oscil- tary Sciences! It gives me great pleasure loscope, and Francesca Smith’s paleohydrological investigation of to update you, the alumni and friends of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Further, Andy and Steve the department, on the many interesting both await decisions on their NSF-CAREER grant proposals, and developments that have recently taken place within our scholarly Steve was just named a distinguished lecturer by the Mineralogical community. In the past year, the department has continued to build Society of America. upon the momentum established by several signifi cant changes I Activity within the senior ranks of the faculty has matched the have previously detailed for you—including the appointment of hectic pace of our junior faculty members. Craig Bina, in particular fi ve promising new faculty members, the implementation of a has been very busy lately. After spending much of the past academic new undergraduate curriculum, year in Japan as a visiting schol- and the initiation of a new fi eld ar at the University of Tokyo’s trip program—making the past Earthquake Research Institute twelve months an exciting time and the Geodynamics Research for our faculty and students. Institute at Ehime University, he Before I begin recounting became WCAS associate dean the recent activities of our de- for research and graduate studies partment members, though, let upon returning to the U.S. Two me once again extend a resound- other faculty members recently ing thank you for last year’s earned impressive honors: Seth unprecedented level of alumni Stein was named William Deer- giving. -

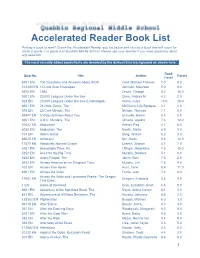

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE MICHAEL JOHN NEUFELD Space History Division (MRC 311) office: (202) 633-2434 National Air and Space Museum fax: (202) 786-2947 Smithsonian Institution [email protected] P.O. Box 37012 Washington, DC 20013-7012 EDUCATION 1970-74 University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta. B.A.(First Class Honours), History. 1974-76 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. M.A., History. 1978-84 The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. M.A., Ph.D., History. Dissertation: "From Artisans to Workers: The Transformation of the Skilled Metalworkers of Nuremberg, 1835-1905." RESEARCH AND TEACHING POSITIONS 1983-85 Clarkson University, Potsdam, New York. Part-time Assistant Professor (1984-85), Part-time Instructor (1983-84). 1985-86 State University of New York College at Oswego. Visiting Assistant Professor. 1986-88 Colgate University, Hamilton, New York. Visiting Assistant Professor. 1988- National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Senior Curator (2014- ), Museum Curator, (1999-2014), Chair, Space History Division (2007-11), Museum Curator in Aeronautics Division (1990-99), Smithsonian Postdoctoral Fellow and NSF Fellow (1989-90), A. Verville Fellow (1988-89). Fall 2001 Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. Senior Lecturer (visiting position). BOOKS The Skilled Metalworkers of Nuremberg: Craft and Class in the Industrial Revolution. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1989. The Rocket and the Reich: Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era. New York: The Free Press, 1995. (Paperback edition, Harvard University Press, 1996; German translation, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, 1997, 2nd ed. Henschel Verlag, 1999; paperback and e-book edition, March 2015 2 Smithsonian Books, 2013). Winner of the 1995 AIAA History Manuscript Award and the 1997 SHOT Dexter Prize. -

The Apollo Spacecraft Chronology, Takes up the Story Where the First Left Off, in November 1962

A CHRONOLOGY NASA SP-4009 THE APOLLO SPACECRAFT A CHRONOLOGY VOLUME II November 8, 1962--September 80, 1964 by Mary Louise Morse and Jean Kernahan Bays THE NASA HISTORICAL SERIES Scientific and Technical ln[ormation Office 1973 /LS.P,. / NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION Washington, D.C. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Price $3.20 Stock Number 3300-0455 (Paper Cover) Library o] Congress Catalog Card Number 69-60008 FOREWORD This, tile second volume of the Apollo Spacecraft Chronology, takes up the story where the first left off, in November 1962. The first volume dealt with the birth of the Apollo Program and traced its early development. The second concerns its teenage period, up to September 30, 1964. By late 1962 the broad conceptual design of the Apollo spacecraft and the Apollo lunar landing mission was complete. The Administrator formally advised the President of the United States on December 10 that NASA had selected lunar orbit rendezw)us over direct ascent and earth orbit rendezvous as the mode for landing on the moon. All major spacecraft contractors had been selected; detailed system design and early developmental testing were under way. On October 20, 1962, soon after Wally Schirra's six-orbit mission in .Sigma 7, the first formal overall status review of the Apollo spacecraft and flight mission effort was given to Administrator James E. _Vebb. The writer of this foreword, who was then the Assistant Director for Apollo Spacecraft Development, recalls George Low, then Director of Manned Spacecraft and Flight Missions trader D. -

Odd Year Nur-Rn-Lic-30550 G

LicenseNumber FirstName MiddleName LastName RenewalGroup NUR-LPN-LIC-6174 DOLORES ROSE AABERG 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-30550 GRETCHEN ELLEN AAGAARD-SHIVELY 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-128118 CAMBRIA LAUREN AANERUD 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-25862 SOPHIA SABINA AANSTAD 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-APRN-LIC-124944 ERIN EDWARD AAS 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-105371 ERIN EDWARD AAS 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-34536 BRYON AAS 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-39208 JULIA LYNN AASEN 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-APRN-LIC-130522 LORI ANN AASEN 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-130520 LORI ANN AASEN 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-21015 DEBBIE ABAR 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-APRN-LIC-130757 LUKE G ABAR 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-130756 LUKE GORDON ABAR 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-31911 AIMEE KRISTINE ABBOTT 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-29448 DENISE M ABBOTT 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-131150 SARAH FRANCES ABBOTT 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-LPN-LIC-31701 ANGIE ABBOTT 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-LPN-LIC-33325 HEIDI ABBOTT 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-LPN-LIC-4920 LORI ANN ABBOTT 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-LPN-LIC-97426 DAYMON ABBOTT Expired - 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-13260 ROBERT C ABBOTT Expired - 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-17858 MONICA MAY ABDALLAH 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-48890 STEVEN P ABDALLAH 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-APRN-LIC-101391 LANEICE LORRAINE ABDEL-SHAKUR Expired - 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-101333 LANEICE LORRAINE ABDEL-SHAKUR Expired - 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-96606 RENDI L ABEL 2018 - EVEN YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-97338 LAURA ANN ABEL 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-69876 LACEY ANN ABELL 2019 - ODD YEAR NUR-RN-LIC-131932 -

1967 Spaceport News Summary

1967 Spaceport News Summary Followup From the Last Spaceport News Summary Of note, the 1963, 1964 and 1965 Spaceport News were issued weekly. Starting with the July 7, 1966, issue, the Spaceport News went to an every two week format. The Spaceport News kept the two week format until the last issue on February 24, 2014. Spaceport Magazine superseded the Spaceport News in April 2014. Spaceport Magazine was a monthly issue, until the last and final issue, Jan./Feb. 2020. The first issue of Spaceport News was December 13, 1962. The two 1962 issues and the issues from 1996 forward are at this website, including the Spaceport Magazine. All links were working at the time I completed this Spaceport News Summary. In the March 3, 1966, Spaceport News, there was an article about tool cribs. The Spaceport News article mentioned “…“THE FIRST of 10 tool cribs to be installed and operated at Launch Complex 39 has opened…”. The photo from the article is below. Page 1 Today, Material Service Center 31 is on the 1st floor of the VAB, on the K, L side (west side) of the building. If there were 10 tool cribs, as mentioned in the 1966 article, does anyone know the story behind the numbering scheme? Tool crib #75? From The January 6, 1967, Spaceport News From page 1, “Launch Team Personnel Named”. A portion of the article reads “Key launch team personnel for the manned flight of Apollo/Saturn 204 have been announced. The 204 mission, to be launched from KSC’s Complex 34, will be the first in which astronauts will fly the three-man Apollo spacecraft.