John Knipe Final Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Antropoly Journal.Indd

Irish Journal of Anthropology Volume 13(2) 2010 1 Irish Journal of Anthropology Volume 13(2) 2010 Special Section: Health, Care, and Death Winning Essay: AAI Annual Postgraduate Essay Prize ‘Genocide site and memorial, Ntarama church, Rwanda (Photo: Eadaoin O’Brien) Volume 13(2) 2010 ISSN: 1393-8592 Irish Journal of Anthropology !e Irish Journal of Anthropology is the organ of the Anthropological Association of Ireland. As such, it aims to promote the discipline of anthropology on the island of Ireland, north and south. It seeks to provide coverage of Irish-related matters and of issues in general anthropology and to be of interest to anthropologists inside and outside academia, as well as to colleagues in a range of other disciplines, such as Archaeology, Cultural Studies, Development Studies, Ethnology and Folk Studies, Gaeilge, Irish Studies, and Sociology. Editor: Dr Séamas Ó Síocháin, Department of Anthropology, NUI Maynooth. [email protected] Associate Editor: Dr Fiona Magowan, School of History and Anthropology, !e Queen’s University of Belfast. f.magowan@ qub.ac.uk Editorial Advisory Board: Dr Dominic Bryan, School of History and Anthropology, !e Queen’s University of Belfast Dr Anthony Buckley, Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, Cultra, Co. Down Dr Maurna Crozier, Northern Ireland Community Relations Council, Belfast Dr Fiona Larkan, Department of Anthropology, NUI Maynooth Dr John Nagle, Lecturer in Anthropology, University of East London Dr Carles Salazar, University of Lleida, Spain Professor Elizabeth Tonkin, Oxford, England Book Review Editors: Dr Chandana Mathur, Department of Anthropology, NUI Maynooth. [email protected]; Professor Máiréad Nic Craith, University of Ulster, Magee Campus. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Arcana & Curiosa

ARCANA & CURIOSA MY PERSONAL LIBRARY * Notes: * The data listed here have been exported from an .fp5 file and they may contain some formatting glitch. Any ambiguities however may be solved by consulting the websites quoted in the records of downloaded materials and/or the main online OPACs, especially the University of Manchester’s COPAC (http://copac.ac.uk/) and OPALE, the online catalogue of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (http://catalogue.bnf.fr/). * This catalogue included printed materials as well as electronic resources published online; there is no separation of the two in sections, but all are recorded in the same database for quick reference, because I don’t always remember whether my copy of a certain work is printed or electronic. * The records are listed A-Z by surname of first author and first word in the title (articles included). * A passage to the Afterworld, http://www.knowth.com/newgrange.htm, download aprile 2003, ripubblicato da «The World of Hibernia», Cultura materiale e archeologia A Proper newe Booke of Cokerye (mid-16th c.), http://www.staff.uni- marburg.de/~gloning/bookecok.htm, download maggio 2004, Cultura materiale e archeologia Ad fontes: gnostic sources in the BPH, J.R. Ritman Library -- Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica. The Library of Hermetic Philosophy in Amsterdam, http://www.xs4all.nl/~bph/, download agosto 2002, Alchimia Aesch-Mezareph, traduzione inglese di W. Wynn Westcott, The Alchemy Web, http://www.levity.com/alchemy, download ottobre 2001, Adam McLean, Alchimia Alchemical and chemical -

Universal Dependencies for Manx Gaelic

Universal Dependencies for Manx Gaelic Kevin P. Scannell Department of Computer Science Saint Louis University St. Louis, Missouri, USA [email protected] Abstract Manx Gaelic is one of the three Q-Celtic languages, along with Irish and Scottish Gaelic. We present a new dependency treebank for Manx consisting of 291 sentences and about 6000 tokens, annotated according to the Universal Dependency (UD) guidelines. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first annotated corpus of any kind for Manx. Our annotations generally follow the conventions established by the existing UD treebanks for Irish and Scottish Gaelic, although we highlight some areas where the grammar of Manx diverges, requiring new analyses. We use 10- fold cross validation to evaluate the accuracy of dependency parsers trained on the corpus, and compare these results with delexicalized models transferred from Irish and Scottish Gaelic. 1 Introduction Manx Gaelic, spoken primarily on the Isle of Man, is one of the three Q-Celtic (or Goidelic) languages, along with Irish and Scottish Gaelic. Although the language fell out of widespread use during the 19th and 20th centuries, it has seen a vibrant revitalization movement in recent years. The number of speakers is now growing, thanks in part to a Manx-language primary school on the island. The language also has a strong online presence relative to the size of the community. Several Manx dictionaries were published in the 19th and 20th centuries, and a number of these have been digitized in recent years and published online.1 The full text of the Bible, originally published in the 18th century, is also available and provides an easily-accessible source of parallel text.2 In terms of spoken language, the Irish Folklore Commission recorded fluent speakers on the Isle of Man in 1948, and those recordings are now available digitally as well.3 Outside of these corpus resources, very little advanced language technology exists for Manx. -

A1a13os Mo1je3 A11110 1Eujnor

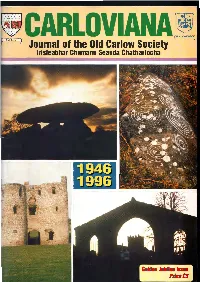

§Gllt,I IISSI Nlltllf NPIIII eq:101Jeq1eq3.epueas uuewnq3 Jeqqea1s1JI A1a13os Mo1Je3 PIO a11110 1euJnor SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL - 9-13 DUBLIN STREET SOTHERN AUCTIONEERS LTD A Personal Hotel ofQuality Auctioneers. Valuers, Insurance Brokers, 30 Bedrooms En Suite, choice ofthree Conference Rooms. 37 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31218. Fax.0503 43765 Weddings, functions, Dinner Dances, Private Parties. District Office: Irish Nationwide Building Society Food Served ALL Day. Phone: 0503/31621 FLY ONTO ED. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD O'CONNOR'S GREEN DRAKE INN, BORRIS Fuel Merchant, Authorised Ergas Stockists Lounge and Restaurant - Lunches and Evening Meals POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31367 Weddings and Parties catered for. GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA IRISH PERMANENT PLC. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY 122/3 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW CARLOW Phone:0503/43025,43690 Seamus Walker - Manager Carlow DEERPARK SERVICE STATION FIRST NATIONAL BUILDING SOCIETY MARKET CROSS, CARLOW Tyre Service and Accessories Phone: 0503/42925, 42629 DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31414 THOMAS F. KEHOE MULLARKEY INSURANCES Specialist Lifestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings COURT PLACE, CARLOW Property and Estate Agent Phone: 0503/42295, 42920 Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society General Insurance - Life and Pensions - Investment Bonds 57 DUBLIN STREET CARLOW. Telephone: 0503/31378/31963 Jones Business Systems GIFTS GALORE FROM Sales and Service GILLESPIES Photocopiers * Cash Registers * Electronic Weighing Scales KENNEDY AVENUE, CARLOW Car Phones * Fax Machines * Office Furniture* Computer/Software Burrin Street, Carlow. Tel: (0503) 32595 Fax (0503) 43121 Phone: 0503/31647, 42451 CARLOW PRINTING CO. LTD DEVOY'S GARAGE STRAWHALL INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, CARLOW TULLOW ROAD, CARLOW For ALL your Printing Requirements. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

Gaelic Language Plan - Second Edition February 2018 to September 2022

‘Edinburgh is a city that develops and supports more fluent and confident Gaelic speakers, and promotes thriving Gaelic communities and cultures’. The City of Edinburgh Council DRAFT Gaelic Language Plan - Second Edition February 2018 to September 2022 Prepared under Section 3 of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 Final DRAFT for final public consultation and engagement – 2 October 2017 to 15 December 2017 Please find details of the consultation and engagement at: https://consultationhub.edinburgh.gov.uk/ 1 Foreword Councillor Lewis Ritchie – The City of Edinburgh Gaelic language and culture. We now have a new Gaelic medium Council Gaelic Champion education primary school, expanded Gaelic learning across our schools, and improved community relations with Gaelic communities. However, I recognise that the position of Gaelic in the city is extremely fragile. When a parent chooses to educate their child in Gaelic, they take a massive leap of faith in the Council. Consequently, we owe a Gaelic is an integral part of our shared heritage and national tremendous duty of care to these parents, and their children. identity, and is a unique and essential feature of Scotland’s rich Gaelic pupils have a right to demand the highest possible quality cultural tapestry. learning experience that any of their English language It is an aspect of our cultural life that simply must be protected. counterparts might receive in Edinburgh’s schools. We therefore Not for romantic or nostalgic reasons, but out of recognition that have a duty to ensure that they leave their time in school with a Gaelic remains a vital, visceral language that is constantly sense of achievement and attainment, and confidence and changing and evolving. -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Pages 1–9, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, July 27–31, 2011

EMNLP 2011 DIALECTS2011 Proceedings of the First Workshop on Algorithms and Resources for Modelling of Dialects and Language Varieties July 31, 2011 Edinburgh, Scotland, UK c 2011 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-937284-17-6 / 1-937284-17-4 ii Introduction Language varieties (and specifically dialects) are a primary means of expressing a person’s social affiliation and identity. Hence, computer systems that can adapt to the user by displaying a familiar socio-cultural identity are expected to raise the acceptance within certain contexts and target groups dramatically. Although the currently prevailing statistical paradigm has made possible major achievements in many areas of natural language processing, the applicability of the available methods is generally limited to major languages / standard varieties, to the exclusion of dialects or varieties that substantially differ from the standard. While there are considerable initiatives dealing with the development of language resources for minor languages, and also reliable methods to handle accents of a given language, i.e., for applications like speech synthesis or recognition, the situation for dialects still calls for novel approaches, methods and techniques to overcome or circumvent the problem of data scarcity, but also to enhance and strengthen the standing that language varieties and dialects have in natural language processing technologies, as well as in interaction technologies that build upon the former. What made us think that a such a workshop would be a fruitful enterprise was our conviction that only joint efforts of researchers with expertise in various disciplines can bring about progress in this field. -

APPENDIX 3 SCHEDULE 4S Issue 1 Outer

APPENDIX 3 SCHEDULE 4s Issue 1 Outer Hebrides Proposed Plan: General Plan Context Reporter: National Marine Plan referencing Development plan Policy cross referencing reference: Biodiversity Landscape Body or person(s) submitting a representation raising the issue (including reference number): Kate Dawson (001) Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (021) Urras Oighreachd Ghabhsainn (Galson Trust) (030) Carloway Estate Trust (033) Bord na Gaidhlig (037) Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation (036) Scottish Government (028) John Muir Trust (022) Scottish Natural Heritage (029) Provision of the Some general comments on the Plan content and Vision, development plan to policy cross referencing, reference to the National Marine which the issue Plan, and Landscape policy. relates: Planning authority’s summary of the representation(s): Plan – General Comments, Context and Vision The Carloway Estate Trust (033), seeks clearer link made in the documents to the anticipated increasing impact community ownership will have on environmental and economic sustainability. Bord Na Gaidhlig (037) acknowledge that the Plan ‘Context’ section recognises Gaelic but suggest this could be strengthened. The Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation (036) note that it would be helpful if the importance of marine fish farming were noted in the ‘Context’ section of the Plan. National Marine Plan referencing Scottish Government (028) and the Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation (036) seek that reference to the National Marine Plan is added, clarified or corrected in several places throughout the Plan to ensure due regard is given the National Marine Plan. Policy cross referencing The John Muir Trust (022) and Scottish Natural Heritage (029) have suggested a number of policy cross references between policies and within Plan policies.