Irish Antropoly Journal.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arcana & Curiosa

ARCANA & CURIOSA MY PERSONAL LIBRARY * Notes: * The data listed here have been exported from an .fp5 file and they may contain some formatting glitch. Any ambiguities however may be solved by consulting the websites quoted in the records of downloaded materials and/or the main online OPACs, especially the University of Manchester’s COPAC (http://copac.ac.uk/) and OPALE, the online catalogue of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (http://catalogue.bnf.fr/). * This catalogue included printed materials as well as electronic resources published online; there is no separation of the two in sections, but all are recorded in the same database for quick reference, because I don’t always remember whether my copy of a certain work is printed or electronic. * The records are listed A-Z by surname of first author and first word in the title (articles included). * A passage to the Afterworld, http://www.knowth.com/newgrange.htm, download aprile 2003, ripubblicato da «The World of Hibernia», Cultura materiale e archeologia A Proper newe Booke of Cokerye (mid-16th c.), http://www.staff.uni- marburg.de/~gloning/bookecok.htm, download maggio 2004, Cultura materiale e archeologia Ad fontes: gnostic sources in the BPH, J.R. Ritman Library -- Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica. The Library of Hermetic Philosophy in Amsterdam, http://www.xs4all.nl/~bph/, download agosto 2002, Alchimia Aesch-Mezareph, traduzione inglese di W. Wynn Westcott, The Alchemy Web, http://www.levity.com/alchemy, download ottobre 2001, Adam McLean, Alchimia Alchemical and chemical -

A1a13os Mo1je3 A11110 1Eujnor

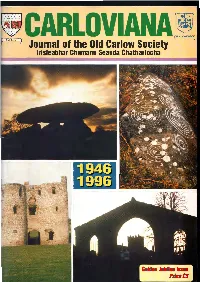

§Gllt,I IISSI Nlltllf NPIIII eq:101Jeq1eq3.epueas uuewnq3 Jeqqea1s1JI A1a13os Mo1Je3 PIO a11110 1euJnor SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL - 9-13 DUBLIN STREET SOTHERN AUCTIONEERS LTD A Personal Hotel ofQuality Auctioneers. Valuers, Insurance Brokers, 30 Bedrooms En Suite, choice ofthree Conference Rooms. 37 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31218. Fax.0503 43765 Weddings, functions, Dinner Dances, Private Parties. District Office: Irish Nationwide Building Society Food Served ALL Day. Phone: 0503/31621 FLY ONTO ED. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD O'CONNOR'S GREEN DRAKE INN, BORRIS Fuel Merchant, Authorised Ergas Stockists Lounge and Restaurant - Lunches and Evening Meals POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31367 Weddings and Parties catered for. GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA IRISH PERMANENT PLC. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY 122/3 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW CARLOW Phone:0503/43025,43690 Seamus Walker - Manager Carlow DEERPARK SERVICE STATION FIRST NATIONAL BUILDING SOCIETY MARKET CROSS, CARLOW Tyre Service and Accessories Phone: 0503/42925, 42629 DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31414 THOMAS F. KEHOE MULLARKEY INSURANCES Specialist Lifestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings COURT PLACE, CARLOW Property and Estate Agent Phone: 0503/42295, 42920 Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society General Insurance - Life and Pensions - Investment Bonds 57 DUBLIN STREET CARLOW. Telephone: 0503/31378/31963 Jones Business Systems GIFTS GALORE FROM Sales and Service GILLESPIES Photocopiers * Cash Registers * Electronic Weighing Scales KENNEDY AVENUE, CARLOW Car Phones * Fax Machines * Office Furniture* Computer/Software Burrin Street, Carlow. Tel: (0503) 32595 Fax (0503) 43121 Phone: 0503/31647, 42451 CARLOW PRINTING CO. LTD DEVOY'S GARAGE STRAWHALL INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, CARLOW TULLOW ROAD, CARLOW For ALL your Printing Requirements. -

English As We Speak It in Ireland

ENGLISH AS WE SPEAK IT IN IRELAND. ENGLISH AS WE SPEAI^ IT IN IRELAND P. W. JOYCE, LLD., T.O.D., M.R.I.A. One of the Commissioners for the Publication of the Ancient Laws of Ireland Late Principal of the Government Training College, Marlbcrough Street, Dublin Late President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries, Ireland THE LIFE OF A PEOPLE IS PICTURED IN THEIR SPEECH. LONDON : LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO. DUBLIN: M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. i\ 1910 . b PEEFACE. THIS book deals with the Dialect of the English Language that is spoken in Ireland. As the Life of a people according to our motto is pictured in their speech, our picture ought to be a good one, for two languages were concerned in it Irish and English. The part played by each will be found specially set forth in and VII and in farther detail Chapters IV ; throughout the whole book. The articles and pamphlets that have already appeared on this interesting subject which are described below are all short. Some are full of keen observation but are lists ; very many mere of dialectical words with their meanings. Here for the first time in this little volume of mine our Anglo-Irish Dialect is subjected to detailed analysis and systematic classification. I have been collecting materials for this book for more than not indeed twenty years ; by way of constant work, but off and on as detailed below. The sources from which these materials were directly derived are mainly the following. First. My own memory is a storehouse both of idiom and for the reason vocabulary ; good that from childhood to early manhood I spoke like those among whom I lived the rich dialect VI PREFACE. -

Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Pages 1–9, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, July 27–31, 2011

EMNLP 2011 DIALECTS2011 Proceedings of the First Workshop on Algorithms and Resources for Modelling of Dialects and Language Varieties July 31, 2011 Edinburgh, Scotland, UK c 2011 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-937284-17-6 / 1-937284-17-4 ii Introduction Language varieties (and specifically dialects) are a primary means of expressing a person’s social affiliation and identity. Hence, computer systems that can adapt to the user by displaying a familiar socio-cultural identity are expected to raise the acceptance within certain contexts and target groups dramatically. Although the currently prevailing statistical paradigm has made possible major achievements in many areas of natural language processing, the applicability of the available methods is generally limited to major languages / standard varieties, to the exclusion of dialects or varieties that substantially differ from the standard. While there are considerable initiatives dealing with the development of language resources for minor languages, and also reliable methods to handle accents of a given language, i.e., for applications like speech synthesis or recognition, the situation for dialects still calls for novel approaches, methods and techniques to overcome or circumvent the problem of data scarcity, but also to enhance and strengthen the standing that language varieties and dialects have in natural language processing technologies, as well as in interaction technologies that build upon the former. What made us think that a such a workshop would be a fruitful enterprise was our conviction that only joint efforts of researchers with expertise in various disciplines can bring about progress in this field. -

Ingham County News I)Hoto,) the Projected Figures Were In· Velvety Sky; and Nancy Bray, the Dance

Robert L. Shepard,' 22, Bunlwr I-II II, . fnces .a charge o! ljSSilUlt with Intent lo·commlt murder In the shooting of his former · sJ.s. lcr·in·inw Saturday 'night. Miss 4. Sections- 26 Pages Lolmu Cmft, 17, was 'shot twice • In n fracas at the home 'of Sl]ep· nt·rl's formcr wffe, Mrs. Norma Shr.pard; on DeCnmp road. 'Miss Okemos Backs Cm[l Is In F'ootc hospital, ,Jack· son, where her conclftlon is re. ported us good. ' School Plan. · Many Appeal Valu'ations Shepm·d · waived examination . On the third time around O!tc· mos school electors approved a Assessments caused-heavy traf. • wl10n he appearl!d before ~liHtice his family and under the charter doubled m· tripled, too. In a few of the Peace Roy W. Adams bond Issue for school hnpt·ovc· tic at tile city hall all day Tues· day and on Wcdncsdlly night. was ineligible to continue as a cases taxpayers expressed agree: Wednesday morning. Shepat•d ments: Tuesday's vote ori issuance member of the board of review. mcnt with the figures on theh· \Viis hounrl over to circuit court, of ·.$2,100,000 in bonds was 1,247 Seventy-two propertY owners for and· 253 aga.inst. appeared before the Mason board It wasn't unU! a special coun· own property hut. wonclet·ecJ about held on bond of $50,000. cil meeting Tuesday night that the figures of their neighbors, Two previous proposals lor of rElvJew to· contest or Inquire M t·s. RhP,)at·rl harl J>'aniled n about new property valuation Stroud was nppointcd to !lll the, Tho big·J.:'e.~t: cll•h•J.:'ution date with IIat·ry M, Smith, 32, of $3,500,0()0 and $2,6()0,000 were de· figures. -

Xerox University Microfilms 900 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 49100 Ll I!

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good (mage of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Shopkindly That Has Been Missed, Notify the Business and Give Them the Opportunity to Remedy It Rather Than Posting on Social Media

SPECIAL FEATURE: Life Less Ordinary Living in a pandemic People from around West Cork share their experiences. www.westcorkpeople.ie & www.westcorkfridayad.ie October 2 – October 30, 2020, Vol XVI, Edition 218 FREE Old Town Hall, McCurtain Hill, Clonakilty, Co. Cork. E: [email protected] P: 023 8835698 SILENCE IS GOLDEN. NEW PEUGEOT e-208 FULL ELECTRIC From Direct Provision to Cork Persons of the Month: Izzeddeen and wife Eman Alkarajeh left direct provision in Cork and, together with their four children, overcame all odds to build a new life and successful Palestinian food business in Cork. They are pictured at their Cork Persons of Month award presentation with (l-r) Manus O’Callaghan and award organiser, George Duggan, Cork Crystal. Picture: Tony O’Connell Photography. *Offer valid until the end of August. CLARKE BROS LTD Main Peugeot Dealer, Clonakilty Road, Bandon, Co. Cork. Clune calls on Government to “mind our air routes” Tel: 023-8841923CLARKE BROS Web: www.clarkebrosgroup.ie ction is needed on the Avia- Irish Aviation Sector to recover from but also to onward flights through the to Ireland’s economy and its economic (BANDON) LTD tion Recovery Taskforce Re- the impact of Covid 19. One of the international airline hubs as well as recovery. Main Peugeot Dealers port to ensure we have strong recommendations of the Aviation excellent train access across Europe. The report said that a stimulus Clonakilty Road, Aregional airports post-Covid. This Recovery Taskforce Report was to MEP Clune added: “This is a very package should be put in place con- is according to Ireland South MEP provide a subvention per passenger difficult time for our airlines and air- currently for each of Cork, Shannon, Bandon Deirdre Clune who said it should be at Cork, Shannon and other Regional ports but we must ensure that they get Ireland West, Kerry and Donegal Co. -

Research Bibliography:Resources on the Study of the Healing Cultures In

Research Bibliography SOURCES ON THE STUDY OF THE HEALING CULTURES IN IRELAND AND THE BRITISH ISLES Stephany Hoffelt | BA HAS | May 11, 2016 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 General Reference ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Prehistory ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Women and Healing .......................................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. Digital Receipt Book Collections ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Irish Reference ................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Scottish Reference ......................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Anglo Saxon Reference ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Summit I**R 8En4n$ Smmmtt for C7 Yeart

»-"*-, f" .--' % geadsfa-HeraM mmm Read fhe Herald ^ Local News For Local News Summit i**r 8en4n$ Smmmtt for C7 Yeart •t mnd Summit Record .-?'i?r , itil M 4 III MA ftAt Cfty rays of Cranes $12406 in New County Tax Pbn By Candidates for City Votes Summit will be nicked for an The Senatorial battle of the Cranes was brought before additional $12,036 In county taxes Summit voter* last Friday evening at a candidates' meet- this rear under the new "tn* i ing held at City Hall under the sponsorship of the City value" equalization program, ae* Republican Couimittee. cording to a report issued lad Despite a heavy rain the Council chamber was filled week-end by the County Tax to capacity by voters who turned out to hear the various Repub- Board. Under the new "table Sum- Jican mit will pay a tax of $458,745 as candidate* seeking the compared with $446,71* under Contests Plrty nowinatiott for county and the old system. One of the hardest hit com- Since there is no Primary con- munities under Uie new plan is Following ii a brief summary teat for nay oi the municipal of- Berkeley Heights where a f8fc> of the Primary Election that will fices, candidates for those berths #0tf increase is in prespect. '13K held next Tuesday, April 17. confined their remark»fto brief; y ; new equalization tax for that Local polling placet witt be open introduction*. ' "t" community will be , $m,m. from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. Sample The local candidates are K. -

Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960

Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 1 15/07/2013 12:33:33 Reappraisals in Irish History Editors Enda Delaney (University of Edinburgh) Maria Luddy (University of Warwick) Reappraisals in Irish History offers new insights into Irish history, society and culture from 1750. Recognising the many methodologies that make up historical research, the series presents innovative and interdisciplinary work that is conceptual and interpretative, and expands and challenges the common understandings of the Irish past. It showcases new and exciting scholarship on subjects such as the history of gender, power, class, the body, landscape, memory and social and cultural change. It also reflects the diversity of Irish historical writing, since it includes titles that are empirically sophisticated together with conceptually driven synoptic studies. 1. Jonathan Jeffrey Wright, The ‘Natural Leaders’ and their World: Politics, Culture and Society in Belfast, c.1801–1832 Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 2 15/07/2013 12:33:33 Reading the Irish Woman Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 GerArdiNE MEANEY, MARY O’Dowd AND BerNAdeTTE WHelAN liVerPool UNIVersiTY Press Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 3 15/07/2013 12:33:33 reading the irish woman First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Gerardine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan The rights of Gerardine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan to be identified as the authors of this book have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY and FOLKLORE

the encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY AND FOLKLORE Patricia Monaghan The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore Copyright © 2004 by Patricia Monaghan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Monaghan, Patricia. The encyclopedia of Celtic mythology and folklore / Patricia Monaghan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Mythology, Celtic—Encyclopedias. 2. Celts—Folklore—Encyclopedias. 3. Legends—Europe—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BL900.M66 2003 299'.16—dc21 2003044944 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION iv A TO Z ENTRIES 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 479 INDEX 486 INTRODUCTION 6 Who Were the Celts? tribal names, used by other Europeans as a The terms Celt and Celtic seem familiar today— generic term for the whole people. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Cover . i Cover Information . ii Board of Regents. iii Introduction From the Chair . iv Acknowledgements . v Table of Contents. x CURRICULUM CONTENTS What Do the Erie Canal, Union Soldiers, The Quakers, Annie Moore, and Frederick Douglass Have to do with the Great Irish Famine? . 2 How To Use the Curriculum . 3 Understanding the Curriculum Sections . 4 Recommended Books for The Great Irish Famine Curriculum. 5 Clusters of Activities. 10 Kinds of Student Writing Used in The Great Irish Famine Curriculum . 15 Literature in The Great Irish Famine Curriculum . 19 The Great Irish Famine Curriculum Bibliography. 21 Discography. 28 Famine Videos . 29 THE GREAT IRISH FAMINE CURRICULUM A curriculum for all subjects, based on the New York State learning standards, using primary sources, literature, dance and music, mathematics, history, science, art and theatre, geography, economics, government, career development, and technology Our Great Irish Famine logo is the bronze and stone sculpture by Fred Conlon called Faoin Sceach [FWEEN Skack, Under the Hawthorn]. It stands in the famine graveyard in Sligo. Conlon wrote this description of Faoin Sceach: This Bronze Tree stands as a symbol of dignity. It marks the final resting place of the unnamed dead of this area who perished in the Great Famine of 1845-1847. An Gorta Mór (The Great Hunger) was like a never-ending win ter. Its chill of desolation brought hunger, disease, and death. In Ireland the lone tree or Sceach was held in a position of high importance from early Celtic mythology to recent times. The boulder stones surrounding the base allude to ancient forms of burial.