Universal Dependencies for Manx Gaelic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

Why Study Bilingualism? Bilingualism Is Popular Bilingualism Is HOT! Bilingualism Is HOT! • Policy! – How to “Integrate” Non-English-Speaking Children

Why study bilingualism? Bilingualism is popular Bilingualism is HOT! Bilingualism is HOT! • Policy! – How to “integrate” non-English-speaking children. – How to teach languages more efficiently. • Understanding the mind – Language and cognition – Different languages -> ? Bilingualism: Hotter than phlogiston Examples of multilingual regions (from wikipedia) Many countries, such as Belgium, which are officially multilingual, may have many monolinguals in their population. Offically monolingual countries, on the other hand, such as France, can have sizable multilingual populations. Bilingualism: it doesn’t make Myths ! a majority of the population in sub-Saharan Africa is multilingual. Under its 1996 Constitution, South Africa has 11 official languages including Zulu, Xhosa, Afrikaans and English. ! In Kenya, educated people will typically speak a minimum of three languages: a tribal language (such as Bukusu), the national language " Swahili, and English, which is the medium used in teaching all over the country.! Brussels, the bilingual capital of Belgium (15% Dutch-speaking) Bilingualism is HOT! ! Canada is officially bilingual under the Official Languages Act and the Constitution of Canada that require the federal government to deliver services in both official languages. As well, minority • Learning more than one language confuses a language rights are guaranteed where numbers warrant. Approximately 25% of Canadians speak French. See Bilingualism in Canada you dumber ! the Canadian province of Quebec, (10% English-speaking) Note: Although there is a relatively sizable English-speaking population in Quebec, French is the only official language. ! the province of New Brunswick, Canada (35% French-speaking) New Brunswick is the only province in Canada with two official languages. child. ! there are also significant French language minorities in the provinces of Ontario and Manitoba. -

A Major Wordnet for a Minority Language: Scottish Gaelic

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 2812–2818 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC A Major Wordnet for a Minority Language: Scottish Gaelic Gabor´ Bella1, Fiona McNeill2, Rody Gorman3, Caoimh´ın O´ Donna´ıle3, Kirsty MacDonald, Yamini Chandrashekar1, Abed Alhakim Freihat1, and Fausto Giunchiglia1 1University of Trento, via Sommarive, 5, 38123 Trento, Italy 2Heriot–Watt University, Edinburgh, EH14 4AS, Scotland 3Sabhal Mor` Ostaig, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sleat, Isle of Skye, IV44 8RQ, Scotland [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We present a new wordnet resource for Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic minority language spoken by about 60,000 speakers, most of whom live in Northwestern Scotland. The wordnet contains over 15 thousand word senses and was constructed by merging ten thousand new, high-quality translations, provided and validated by language experts, with an existing wordnet derived from Wiktionary. This new, considerably extended wordnet—currently among the 30 largest in the world—targets multiple communities: language speakers and learners; linguists; computer scientists solving problems related to natural language processing. By publishing it as a freely down- loadable resource, we hope to contribute to the long-term preservation of Scottish Gaelic as a living language, both offline and on the Web. Keywords: wordnet, Scottish Gaelic, under-resourced language, minority language, lexical semantics, translation, lexical gap, language diversity 1. -

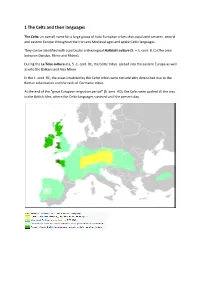

1 the Celts and Their Languages

1 The Celts and their languages The Celts: an overall name for a large group of Indo-European tribes that populated western, central and eastern Europe throughout the Iron and Medieval ages and spoke Celtic languages. They can be identified with a particular archeological Hallstatt culture (8. – 5. cent. B. C) (The area between Danube, Rhine and Rhône). During the La Tène culture era, 5.-1. cent. BC, the Celtic tribes spread into the eastern Europe as well as into the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 1. cent. BC, the areas inhabited by the Celtic tribes were considerably diminished due to the Roman colonization and the raids of Germanic tribes. At the end of the “great European migration period” (6. cent. AD), the Celts were pushed all the way to the British Isles, where the Celtic languages survived until the present day. The oldest roots of the Celtic languages can be traced back into the first half of the 2. millennium BC. This rich ethnic group was probably created by a few pre-existing cultures merging together. The Celts shared a common language, culture and beliefs, but they never created a unified state. The first time the Celts were mentioned in the classical Greek text was in the 6th cent. BC, in the text called Ora maritima written by Hecateo of Mileto (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC). He placed the main Celtic settlements into the area of the spring of the river Danube and further west. The ethnic name Kelto… (Herodotus), Kšltai (Strabo), Celtae (Caesar), KeltŇj (Callimachus), is usually etymologically explainedwith the ie. -

A Comparative Analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham Pillar Stones Clare Jeanne Connelly University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2015 A Partial Reading of the Stones: a Comparative Analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham Pillar Stones Clare Jeanne Connelly University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Communication Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Connelly, Clare Jeanne, "A Partial Reading of the Stones: a Comparative Analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham Pillar Stones" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 799. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/799 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PARTIAL READING OF THE STONES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH OGHAM PILLAR STONES by Clare Connelly A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2015 ABSTRACT A PARTIAL READING OF THE STONES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH OGHAM PILLAR STONES by Clare Connelly The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold Ogham is a script that originated in Ireland and later spread to other areas of the British Isles. This script has preserved best on large pillar stones. Other artefacts with ogham inscriptions, such as bone-handled knives and chalk spindle-whorls, are also known. While ogham has fascinated scholars for centuries, especially the antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries, it has mostly been studied as a script and a language and the nature of its association with particular artefact types has been largely overlooked. -

Gaelic in Contemporary Scotland: Contradictions, Challenges and Strategies

Gaelic in contemporary Scotland: contradictions, challenges and strategies Wilson McLeod University of Edinburgh Since the mid-1970s, efforts to sustain and revitalise Gaelic in Scotland have gained new momentum and prominence, even as the language has continued to decline in demographic terms. Public and institutional provision for Gaelic, most notably in the fields of education and broadcasting, have grown substantially in recent years, and Gaelic has increasingly been perceived as an essential aspect of Scottish cultural distinctiveness, and as such connected (indirectly rather than directly) to the movement for Scottish self-government. This new recognition of Gaelic has now been enshrined in legislation, the Gaelic Language Act (Scotland) 2005, that grants official status to the language for the first time. The Act also establishes a Gaelic language board, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, with powers to undertake strategic language planning for Gaelic at a national level. The continuing decline in speaker numbers and language use suggests that the policies put in place up to now to sustain and promote Gaelic have been inadequate; better integrated and more forceful strategies are urgently needed if the language shift in favour of English is to be reversed. Historical and demographic background Scottish Gaelic ( Gàidhlig ), a member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages that is closely related to Irish and Manx, is generally believed to have been brought to southwest Scotland by settlers from Ireland in the early centuries of the common era, although a minority view questions the Irish origin and suggests that Gaelic may have reached Scotland many centuries earlier (McLeod 2004a: 15). -

Celtic Initial Consonant Mutations - Nghath and Bhfuil?

Celtic initial consonant mutations - nghath and bhfuil? Author: Kevin M Conroy Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/530 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Undergraduate Honors Program Linguistics Celtic initial consonant mutations – nghath and bhfuil ? by Kevin M. Conroy submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of B.A. © copyright by Kevin M. Conroy 2008 Celtic initial consonant mutations – nghath and bhfuil ? Abstract The Insular Celtic languages, such as Irish and Welsh, distinctively feature a morphophonemic process known as initial consonant mutation. Essentially the initial sound of a word changes due to certain grammatical contexts. Thus the word for ‘car’ may appear as carr, charr and gcarr in Irish and as car, gar, char and nghar in Welsh. Originally these mutations result from assimilatory phonological processes which have become grammaticalized and can convey morphological, semantic and syntactic information. This paper looks at the primary mutations in Irish and Welsh, showing the phonological changes involved and exemplifying their basic triggers with forms from the modern languages. Then it explores various topics related to initial consonant mutations including their historical development and impact on the grammatical structure of the Celtic languages. This examination helps to clarify the existence and operations of the initial mutations and displays how small sound changes can have a profound impact upon a language over time. Boston College Undergraduate Honors Program Linguistics Celtic initial consonant mutations – nghath and bhfuil ? by Kevin M. -

APPLICATION of the CHARTER in the UNITED KINGDOM A. Report

Strasbourg, 24 March 2004 ECRML (2004) 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES APPLICATION OF THE CHARTER IN THE UNITED KINGDOM A. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Charter B. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the application of the Charter by the United Kingdom The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provides for a control mechanism to evaluate how the Charter is applied in a State Party with a view to, where necessary, making Recommendations for improving its legislation, policy and practices. The central element of this procedure is the Committee of Experts, set up under Article 17 of the Charter. Its principal purpose is to report to the Committee of Ministers on its evaluation of compliance by a Party with its undertakings, to examine the real situation of regional or minority languages in the State and, where appropriate, to encourage the Party to gradually reach a higher level of commitment. To facilitate this task, the Committee of Ministers adopted, in accordance with Article 15.1, an outline for subsequent periodical reports that a Party is required to submit to the Secretary General. The report should be made public by the State. This outline requires the State to give an account of the concrete application of the Charter, the general policy for the languages protected under Part II and, in more precise terms, all measures that have been taken in application of the provisions chosen for each language protected under Part III of the Charter. The Committee of Experts’ first task is therefore to examine the information contained in the periodical report for all the relevant regional or minority languages on the territory of the State concerned. -

Keltic Researches; Studies in the History and Distribution of the Ancient Goidelic Language and Peoples

KeZcic ReseocRches * STUDIES IN THE HISTORY AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ANCIENT GOIDELIC LANGUAGE AND PEOPLES BY EDWARD WILLIAMS BYRON NICHOLSON, M.A. bodley's librarian in the- university of oxford FELLOW OF THE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION HONORARY MEMBER OF THE CALEDONIAN MEDICAL SOCIETY LONDON: HENRY FROWDE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AMEN CORNER, E.C. NEW YORK: 91 & 93 Fifth Avenue 1904 REESE To THE MEMORY OF HENRY BrADSHAW late Librarian of the University of Cambridge whose discovery of the book of deer and whose palaeographical and critical genius have permanently enriched keltic studies OXFORD : HORACE HART PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The history of ancient and early mediaeval times requires to a far greater extent than more recent history the aid of various other sciences, not the least of which is the science of language. And, although the first object of these Studies was to demonstrate to specialists various unrecognized or imperfectly recognized linguistic facts, the importance of those facts in themselves is much less than that of their historical consequences. The main historical result of this book is the settlement of 1 or of the Pictish the Pictish question ', rather two questions. ' The first of these is What kind of language did the Picts speak?*. The second is 'Were the Picts conquered by the Scots?'. The first has been settled by linguistic and palaeographical methods only : it has been shown that Pictish was a language virtually identical with Irish, differing from that far less than the dialects of some English counties differ from each other. The second has been settled, with very little help from language, by historical and textual methods : it has been made abundantly clear, I think, to any person of impartial and critical mind that the supposed conquest of the Picts by the Scots is an absurd myth. -

Approaching the Pictish Language: Historiography, Early Evidence and the Question of Pritenic

Rhys, Guto (2015) Approaching the Pictish language: historiography, early evidence and the question of Pritenic. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/6285/ . Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Approaching the Pictish Language: Historiography, Early Evidence and the Question of Pritenic Guto Rhys BA, MLitt. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow April, 2015 © Guto Rhys, 2015 2 Abstract The question of ‘the Pictish language’ has been discussed for over four hundred years, and for well over two centuries it has been the subject of ceaseless and often heated debate. The main disagreement focusing on its linguistic categorisation – whether it was Celtic, Germanic (using modern terminology) or whether it belonged to some more exotic language group such as Basque. If it was Celtic then was it Brittonic or Goidelic? The answer to such questions was of some importance in ascertaining to whom the Scottish past belonged. -

The Syntax of the Celtic Languages: a Comparative Perspective Edited by Robert D

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-48160-1 - The Syntax of the Celtic Languages: A Comparative Perspective Edited by Robert D. Borsley and Ian Roberts Excerpt More information Introduction Robert D. Borsley and Ian Roberts 1 Preliminary remarks This book grew out of a conference on Comparative Celtic Syntax held at the University of Wales, Bangor, on 25-7 June 1992.1 Earlier versions of seven of the ten chapters collected here were given at that conference. The idea behind the conference was to bring together researchers working on the syntax of the Celtic languages from a 'principles-and-parameters' perspective (the assumptions behind this perspective are outlined below in section 2.1), and, in particular, to provide a forum where comparative work on Celtic syntax could be presented. The comparative work was intended to be both internal and external to the Celtic family. Hence, one goal of the conference was to encourage those working on Celtic to make comparisons with non-Celtic languages, and to bring relevant phenomena and analyses of Celtic languages to the attention of those working on non-Celtic languages. Although the precise contents differ from the confer- ence, and this volume should not be taken as a conference proceedings, we have compiled this collection with the same general goals in mind. This introduction is intended to provide the background to the chapters that follow, both for those who are unfamiliar with the principles-and-parameters framework and for those who are unfamiliar with the Celtic languages. In this section, we briefly sketch the historical, geographical and social situation of the languages.