The Syntax of the Celtic Languages: a Comparative Perspective Edited by Robert D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting the Insular Celtic Hypothesis Through Working Towards an Original Phonetic Reconstruction of Insular Celtic

Mind Your P's and Q's: Revisiting the Insular Celtic hypothesis through working towards an original phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic Rachel N. Carpenter Bryn Mawr and Swarthmore Colleges 0.0 Abstract: Mac, mac, mac, mab, mab, mab- all mean 'son', inis, innis, hinjey, enez, ynys, enys - all mean 'island.' Anyone can see the similarities within these two cognate sets· from orthographic similarity alone. This is because Irish, Scottish, Manx, Breton, Welsh, and Cornish2 are related. As the six remaining Celtic languages, they unsurprisingly share similarities in their phonetics, phonology, semantics, morphology, and syntax. However, the exact relationship between these languages and their predecessors has long been disputed in Celtic linguistics. Even today, the battle continues between two firmly-entrenched camps of scholars- those who favor the traditional P-Celtic and Q-Celtic divisions of the Celtic family tree, and those who support the unification of the Brythonic and Goidelic branches of the tree under Insular Celtic, with this latter idea being the Insular Celtic hypothesis. While much reconstructive work has been done, and much evidence has been brought forth, both for and against the existence of Insular Celtic, no one scholar has attempted a phonetic reconstruction of this hypothesized proto-language from its six modem descendents. In the pages that follow, I will introduce you to the Celtic languages; explore the controversy surrounding the structure of the Celtic family tree; and present a partial phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic through the application of the comparative method as outlined by Lyle Campbell (2006) to self-collected data from the summers of2009 and 2010 in my efforts to offer you a novel perspective on an on-going debate in the field of historical Celtic linguistics. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Universal Dependencies for Manx Gaelic

Universal Dependencies for Manx Gaelic Kevin P. Scannell Department of Computer Science Saint Louis University St. Louis, Missouri, USA [email protected] Abstract Manx Gaelic is one of the three Q-Celtic languages, along with Irish and Scottish Gaelic. We present a new dependency treebank for Manx consisting of 291 sentences and about 6000 tokens, annotated according to the Universal Dependency (UD) guidelines. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first annotated corpus of any kind for Manx. Our annotations generally follow the conventions established by the existing UD treebanks for Irish and Scottish Gaelic, although we highlight some areas where the grammar of Manx diverges, requiring new analyses. We use 10- fold cross validation to evaluate the accuracy of dependency parsers trained on the corpus, and compare these results with delexicalized models transferred from Irish and Scottish Gaelic. 1 Introduction Manx Gaelic, spoken primarily on the Isle of Man, is one of the three Q-Celtic (or Goidelic) languages, along with Irish and Scottish Gaelic. Although the language fell out of widespread use during the 19th and 20th centuries, it has seen a vibrant revitalization movement in recent years. The number of speakers is now growing, thanks in part to a Manx-language primary school on the island. The language also has a strong online presence relative to the size of the community. Several Manx dictionaries were published in the 19th and 20th centuries, and a number of these have been digitized in recent years and published online.1 The full text of the Bible, originally published in the 18th century, is also available and provides an easily-accessible source of parallel text.2 In terms of spoken language, the Irish Folklore Commission recorded fluent speakers on the Isle of Man in 1948, and those recordings are now available digitally as well.3 Outside of these corpus resources, very little advanced language technology exists for Manx. -

K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

By Bernard Wailes TOP: Seventh century A.D., peoples of Ireland and Britain, with places and areas that are mentioned in the text. BOTTOM: The Ogham stone now in St. Declan’s Cathedral at Ardmore, County Waterford, Ireland. Ogham, or Ogam, was a form of cipher writing based on the Latin alphabet and preserving the earliest-known form of the Irish language. Most Ogham inscriptions are commemorative (e.g., de•fin•ing X son of Y) and occur on stone pillars (as here) or on boulders. They date probably from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. who arrived in the fifth century, occupied the southeast. The British (p-Celtic speakers; see “Celtic Languages”) formed a (kel´tik) series of kingdoms down the western side of Britain and over- seas in Brittany. The q-Celtic speaking Irish were established not only in Ireland but also in northwest Britain, a fifth- THE CASE OF THE INSULAR CELTS century settlement that eventually expanded to become the kingdom of Scotland. (The term Scot was used interchange- ably with Irish for centuries, but was eventually used to describe only the Irish in northern Britain.) North and east of the Scots, the Picts occupied the rest of northern Britain. We know from written evidence that the Picts interacted extensively with their neighbors, but we know little of their n decades past, archaeologists several are spoken to this day. language, for they left no texts. After their incorporation into in search of clues to the ori- Moreover, since the seventh cen- the kingdom of Scotland in the ninth century, they appear to i gin of ethnic groups like the tury A.D. -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

The Relationship Between Official National Languages and Regional and Minority Languages: Ireland

Pádraig Ó Riagáin The relationship between official national languages and regional and minority languages: Ireland Achoimre I gcaitheamh an naoú haois déag agus thús an fhichiú haois is i measc na n-aicmí feirmeoireachta ba bhoichte a d’fhaightí lucht labhartha na Gaeilge, go príomha, agus iad sna limistéir ab iargúlta laistigh den aicme sin. Ainneoin dinimic an mheatha, ó thaobh líon na gcainteoirí Gaeilge de, a bheith seanbhunaithe, sheol an stát nua neamhspleách straitéis leathan teanga sa bhliain 1922 atá mar fhráma polasaí go dtí an lá inniu. Bhain an stát nua Éireannach leas as a chuid údaráis d’fhonn cur leis an luach siombalach, cultúrtha agus eacnamaíoch a bhain le líofacht sa Ghaeilge. In ainneoin an polasaí sin, is mó ná riamh na brúnna agus na deacrachtaí atá roimh líonraí scaipthe lucht labhartha na Gaeilge. Níl líonraí na Gaeilge sách mór ná sách cobhsaí, mar sin, le deimhniú go labhrófaí an Ghaeilge ar bhonn leathan go leor chun an chéad glúin dhátheangach eile a dheimhniú. Teacht slán is ea athbheochan. Ba mhar sin riamh é in Éirinn ó 1922 ar aghaidh. 1. Introduction Together with the related languages of Scottish Gaelic and Manx, Irish comprises the Goidelic group of insular Celtic languages. While it is clear that the language was brought to Ireland by sections of the Celtic peoples who migrated from mid-continen- tal Europe, a precise date for its introduction into Ireland cannot be established. How- ever, evidence from written records suggests that Irish was spoken on the island from at least the early centuries of the Christian era. -

Why Study Bilingualism? Bilingualism Is Popular Bilingualism Is HOT! Bilingualism Is HOT! • Policy! – How to “Integrate” Non-English-Speaking Children

Why study bilingualism? Bilingualism is popular Bilingualism is HOT! Bilingualism is HOT! • Policy! – How to “integrate” non-English-speaking children. – How to teach languages more efficiently. • Understanding the mind – Language and cognition – Different languages -> ? Bilingualism: Hotter than phlogiston Examples of multilingual regions (from wikipedia) Many countries, such as Belgium, which are officially multilingual, may have many monolinguals in their population. Offically monolingual countries, on the other hand, such as France, can have sizable multilingual populations. Bilingualism: it doesn’t make Myths ! a majority of the population in sub-Saharan Africa is multilingual. Under its 1996 Constitution, South Africa has 11 official languages including Zulu, Xhosa, Afrikaans and English. ! In Kenya, educated people will typically speak a minimum of three languages: a tribal language (such as Bukusu), the national language " Swahili, and English, which is the medium used in teaching all over the country.! Brussels, the bilingual capital of Belgium (15% Dutch-speaking) Bilingualism is HOT! ! Canada is officially bilingual under the Official Languages Act and the Constitution of Canada that require the federal government to deliver services in both official languages. As well, minority • Learning more than one language confuses a language rights are guaranteed where numbers warrant. Approximately 25% of Canadians speak French. See Bilingualism in Canada you dumber ! the Canadian province of Quebec, (10% English-speaking) Note: Although there is a relatively sizable English-speaking population in Quebec, French is the only official language. ! the province of New Brunswick, Canada (35% French-speaking) New Brunswick is the only province in Canada with two official languages. child. ! there are also significant French language minorities in the provinces of Ontario and Manitoba. -

A Major Wordnet for a Minority Language: Scottish Gaelic

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 2812–2818 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC A Major Wordnet for a Minority Language: Scottish Gaelic Gabor´ Bella1, Fiona McNeill2, Rody Gorman3, Caoimh´ın O´ Donna´ıle3, Kirsty MacDonald, Yamini Chandrashekar1, Abed Alhakim Freihat1, and Fausto Giunchiglia1 1University of Trento, via Sommarive, 5, 38123 Trento, Italy 2Heriot–Watt University, Edinburgh, EH14 4AS, Scotland 3Sabhal Mor` Ostaig, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sleat, Isle of Skye, IV44 8RQ, Scotland [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We present a new wordnet resource for Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic minority language spoken by about 60,000 speakers, most of whom live in Northwestern Scotland. The wordnet contains over 15 thousand word senses and was constructed by merging ten thousand new, high-quality translations, provided and validated by language experts, with an existing wordnet derived from Wiktionary. This new, considerably extended wordnet—currently among the 30 largest in the world—targets multiple communities: language speakers and learners; linguists; computer scientists solving problems related to natural language processing. By publishing it as a freely down- loadable resource, we hope to contribute to the long-term preservation of Scottish Gaelic as a living language, both offline and on the Web. Keywords: wordnet, Scottish Gaelic, under-resourced language, minority language, lexical semantics, translation, lexical gap, language diversity 1. -

On the Debate Over the Classification of the Language of the South-Western (SW) Inscriptions, Also Known As Tartessian

On the Debate over the Classification of the Language of the South-Western (SW) Inscriptions, also known as Tartessian John T. Koch University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies I. Three and a half theories §1. Many linguists will be interested in Eric Hamp’s 2012 revision of his 1989 Indo-European family tree (both in Hamp 2013). For the present subject, the node called Northwest Indo-European1 is most relevant. The older and newer versions of this branch are redrawn below.2 1 Hamp’s names and descriptive terms for languages are indicated here with bold type rather than quotation marks, as quotation marks are used meaningfully on his trees. 2 Outside of the Italo-Celtic node I have simplified some of the details and omitted some of the bracketed annotations. [ 1 ] §2. The biggest change in this section of the tree is that what had been Northwest Indo-European in 1989 has become two sibling branches in 2012: (I) Northwest Indo-European and (II) Northern Indo-European (“mixture with non-Indo-European”). The latter branch (not included above) comprises: (1) “GERMANO-PREHELLENIC” (whence the siblings Germanic and Prehellenic (substrate geography)3); (2) Thracian, Dacian (as a single node); (3) Cimmerian; (4) Tocharian; and (5) “ADRIATIC- BALTO-SLAVIC” (whence the siblings (a) Balto-Slavic and (b) “ADRIATIC INDO-EUROPEAN” (the latter being the parent of (i) Albanian and (ii) “MESSAPO-ILLYRIAN”).4 Thus, one way in which the 2012 tree is different is that Phrygian alone is now seen as forming a subgroup with Italo-Celtic, whereas the 1989 tree had Italo-Celtic, Tocharian, Phrygian, Messapic, “Illyrian”, and Germanic, all as first-generation descendants of Northwest Indo-European, together with an “EASTERN NODE” (as a sibling in the same generation as Italo-Celtic and so on). -

1 the Celts and Their Languages

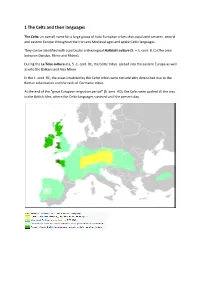

1 The Celts and their languages The Celts: an overall name for a large group of Indo-European tribes that populated western, central and eastern Europe throughout the Iron and Medieval ages and spoke Celtic languages. They can be identified with a particular archeological Hallstatt culture (8. – 5. cent. B. C) (The area between Danube, Rhine and Rhône). During the La Tène culture era, 5.-1. cent. BC, the Celtic tribes spread into the eastern Europe as well as into the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 1. cent. BC, the areas inhabited by the Celtic tribes were considerably diminished due to the Roman colonization and the raids of Germanic tribes. At the end of the “great European migration period” (6. cent. AD), the Celts were pushed all the way to the British Isles, where the Celtic languages survived until the present day. The oldest roots of the Celtic languages can be traced back into the first half of the 2. millennium BC. This rich ethnic group was probably created by a few pre-existing cultures merging together. The Celts shared a common language, culture and beliefs, but they never created a unified state. The first time the Celts were mentioned in the classical Greek text was in the 6th cent. BC, in the text called Ora maritima written by Hecateo of Mileto (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC). He placed the main Celtic settlements into the area of the spring of the river Danube and further west. The ethnic name Kelto… (Herodotus), Kšltai (Strabo), Celtae (Caesar), KeltŇj (Callimachus), is usually etymologically explainedwith the ie. -

First European Symposium in Celtic Studies Erstes Europäisches Keltologie-Symposium Premier Symposium Européen De Celtologie

First European Symposium in Celtic Studies Erstes Europäisches Keltologie-Symposium Premier Symposium Européen de Celtologie 5.–9. August 2013 Universität Trier hp://celtic-symposium.uni-trier.de © Authors, 2013 All rights reserved including for translation, printing, reproduction by copying or other technical means (also in extracts) 2 Abstracts / Zusammenfassungen / Resumés Albrecht, Belinda (Humboldt-Universität, Berlin, DE) Cultural and Linguistic Aspects of Breton Sound Recordings from the Sound Archive of Humboldt-University Berlin. As in 2014 the 100th anniversary of the First World War will be commemorated it is high time to spot light on Breton sound recordings made in German POW camps during World War I. Re - specting the sensibilities concerned with the circumstances as well as the scientific-historical background this communication is an interdisciplinary work by Belinda Albrecht explaining methods of sound recording at that time from the perspective of a scholar of cultural theory and cultural history and Loïc Cheveau looking at implications from a linguist’s point of view. Speech was investigated from the perspective of wrien language. The recordings had to exactly follow a wrien text. In case the speaker could not read there was found an absurd solution: the linguist who assisted the recordings had to prompt the text to the speaker who repeated it into the phonograph. The Breton sound recordings were noted, transcribed and translated from Breton to French and German by Rudolf Thurneysen of whom the original documents can be found in the sound archive. This communication deals with one of the Breton recordings where Thurneysen prompted himself. In this recording, we can hear a soldier from Guidel (near Lorient). -

A Comparative Analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham Pillar Stones Clare Jeanne Connelly University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2015 A Partial Reading of the Stones: a Comparative Analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham Pillar Stones Clare Jeanne Connelly University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Communication Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Connelly, Clare Jeanne, "A Partial Reading of the Stones: a Comparative Analysis of Irish and Scottish Ogham Pillar Stones" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 799. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/799 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PARTIAL READING OF THE STONES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH OGHAM PILLAR STONES by Clare Connelly A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2015 ABSTRACT A PARTIAL READING OF THE STONES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH OGHAM PILLAR STONES by Clare Connelly The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold Ogham is a script that originated in Ireland and later spread to other areas of the British Isles. This script has preserved best on large pillar stones. Other artefacts with ogham inscriptions, such as bone-handled knives and chalk spindle-whorls, are also known. While ogham has fascinated scholars for centuries, especially the antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries, it has mostly been studied as a script and a language and the nature of its association with particular artefact types has been largely overlooked.