K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 7 1-29-2010 Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6. Emily McEwan-Fujita University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation McEwan-Fujita, Emily (2010) "Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/7 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN: 978-83- 7171-849-6. $36.00. Emily McEwan-Fujita, University of Pittsburgh This book's central theme, as the author notes in the preface, is "dimensions of Celtic linguistic presence" as manifested in diverse sociolinguistic contexts. However, the concept of "linguistic presence" gives -

Revisiting the Insular Celtic Hypothesis Through Working Towards an Original Phonetic Reconstruction of Insular Celtic

Mind Your P's and Q's: Revisiting the Insular Celtic hypothesis through working towards an original phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic Rachel N. Carpenter Bryn Mawr and Swarthmore Colleges 0.0 Abstract: Mac, mac, mac, mab, mab, mab- all mean 'son', inis, innis, hinjey, enez, ynys, enys - all mean 'island.' Anyone can see the similarities within these two cognate sets· from orthographic similarity alone. This is because Irish, Scottish, Manx, Breton, Welsh, and Cornish2 are related. As the six remaining Celtic languages, they unsurprisingly share similarities in their phonetics, phonology, semantics, morphology, and syntax. However, the exact relationship between these languages and their predecessors has long been disputed in Celtic linguistics. Even today, the battle continues between two firmly-entrenched camps of scholars- those who favor the traditional P-Celtic and Q-Celtic divisions of the Celtic family tree, and those who support the unification of the Brythonic and Goidelic branches of the tree under Insular Celtic, with this latter idea being the Insular Celtic hypothesis. While much reconstructive work has been done, and much evidence has been brought forth, both for and against the existence of Insular Celtic, no one scholar has attempted a phonetic reconstruction of this hypothesized proto-language from its six modem descendents. In the pages that follow, I will introduce you to the Celtic languages; explore the controversy surrounding the structure of the Celtic family tree; and present a partial phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic through the application of the comparative method as outlined by Lyle Campbell (2006) to self-collected data from the summers of2009 and 2010 in my efforts to offer you a novel perspective on an on-going debate in the field of historical Celtic linguistics. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

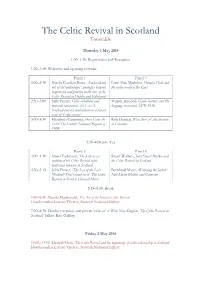

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable Thursday 1 May 2014 1:00–1:30: Registration and Reception 1:30–1:50: Welcome and opening remarks Panel 1 Panel 2 2:00–2:30 Nicola Gordon Bowe, ‘Embroideries Liam Mac Mathúna, Douglas Hyde and out of old mythologies’: analogies between the wider world of the Gael inspiration and practice in the arts of the Celtic Revival in Dublin and Edinburgh 2:30–3:00 Sally Foster, Celtic collections and Wilson McLeod, Gaelic learners and the imperial connections: the V&A, language movement, 1870-1930 Scotland and the multiplication of plaster casts of ‘Celtic crosses’ 3:00–3:30 Elizabeth Cumming, Here Come the Rob Dunbar, Was there a Celtic Revival Celts! The Scottish National Pageant of in Canada? 1908 3:30–4:00 pm: Tea Panel 3 Panel 4 4:00–4:30 Stuart Eydmann, The harp as an Stuart Wallace, John Stuart Blackie and emblem of the Celtic Revival, with the Celtic Revival in Scotland particular reference to Scotland 4:30–5.15 John Purser, ‘The Lay of the Last Bernhard Maier, ‘Widening the Jacket’: Minstrel? Don’t count on it’: The Celtic John Stuart Blackie and Germany Revival in Scottish Classical Music 5:15–5:30: Break 5:30–6:30: Murdo Macdonald, The Art of the Scottish Celtic Revival Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery 7:00–8:30: Drinks reception and private view of A Wide New Kingdom: The Celtic Revival in Scotland, Talbot Rice Gallery. Friday 2 May 2014 10:00–11:00: Donald Meek, The Celtic Revival and the beginnings of Celtic scholarship in Scotland Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D. Joseph, The Ohio State University 0. Introduction A stunning result of linguistic research in the 19th century was the recognition that some languages show correspondences of form that cannot be due to chance convergences, to borrowing among the languages involved, or to universal characteristics of human language, and that such correspondences therefore can only be the result of the languages in question having sprung from a common source language in the past. Such languages are said to be “related” (more specifically, “genetically related”, though “genetic” here does not have any connection to the term referring to a biological genetic relationship) and to belong to a “language family”. It can therefore be convenient to model such linguistic genetic relationships via a “family tree”, showing the genealogy of the languages claimed to be related. For example, in the model below, all the languages B through I in the tree are related as members of the same family; if they were not related, they would not all descend from the same original language A. In such a schema, A is the “proto-language”, the starting point for the family, and B, C, and D are “offspring” (often referred to as “daughter languages”); B, C, and D are thus “siblings” (often referred to as “sister languages”), and each represents a separate “branch” of the family tree. B and C, in turn, are starting points for other offspring languages, E, F, and G, and H and I, respectively. Thus B stands in the same relationship to E, F, and G as A does to B, C, and D. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Václav Blažek (Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic) On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey The purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo-European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non-Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian 0.3. Vladimir Georgiev (1981, 363) included in his Indo-European classification some of the relic languages, plus the languages with a doubtful IE affiliation at all: Tocharian Northern Balto-Slavic Germanic Celtic Ligurian Italic & Venetic Western Illyrian Messapic Siculian Greek & Macedonian Indo-European Central Phrygian Armenian Daco-Mysian & Albanian Eastern Indo-Iranian Thracian Southern = Aegean Pelasgian Palaic Southeast = Hittite; Lydian; Etruscan-Rhaetic; Elymian = Anatolian Luwian; Lycian; Carian; Eteocretan 0.4. -

Thomas Newbolt: Drama Painting – a Modern Baroque

NAE MAGAZINE i NAE MAGAZINE ii CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 EDITORIAL Off Grid - Daniel Nanavati talks about artists who are working outside the established art market and doing well. 6 DEREK GUTHRIE'S FACEBOOK DISCUSSIONS A selection of the challenging discussions on www.facebook.com/derekguthrie 7 THE WIDENING CHASM BETWEEN ARTISTS AND CONTEMPORARY ART David Houston, curator and academic, looks at why so may contemporary artists dislike contemporary art. 9 THE OSCARS MFA John Steppling, who wrote the script for 52nd Highway and worked in Hollywood for eight years, takes a look at the manipulation of the moving image makers. 16 PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT WITH PLYMOUTH COLLEGE OF ART Our special announcement this month is a partnering agreement between the NAE and Plymouth College of Art 18 SPEAKEASY Tricia Van Eck tells us that artists participating with audiences is what makes her gallery in Chicago important. 19 INTERNET CAFÉ Tom Nakashima, artist and writer, talks about how unlike café society, Internet cafés have become. Quote: Jane Addams Allen writing on the show: British Treasures, From the Manors Born 1984 One might almost say that this show is the apotheosis of the British country house " filtered through a prism of French rationality." 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS 21 MONSTER ROSTER INTERVIEW Tom Mullaney talks to Jessica Moss and John Corbett about the Monster Roster. 25 THOUGHTS ON 'CAST' GRANT OF £500,000 Two Associates talk about one of the largest grants given to a Cornwall based arts charity. 26 MILWAUKEE MUSEUM'S NEW DESIGN With the new refurbishment completed Tom Mullaney, the US Editor, wanders around the inaugural exhibition. -

Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm

4 (2017) Book Review 1: 1-4 Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015. 181 pages, £95.00, ISBN (hardcover) 978-1-78316-792-0 REVIEW BY: PHILIP FREEMAN License: This contribution to Entangled Religions is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International). The license can be accessed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or is available from Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbot Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. © 2017 Philip Freeman Entangled Religions 4 (2017) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v4.2017.1-4 Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015. 181 pages, £95.00, ISBN (hardcover) 978-1-78316-792-0 REVIEW BY: PHILIP FREEMAN The modern scholarly and popular fascination with the myths and religion of the early Celts shows no signs of abating—and with good reason. The stories of druids, gods, and heroes from ancient Gaul to medieval Ireland and Wales are among the best European culture has to offer. But what can we really know about the religion and mythology of the Celts? How do we discover genuine pre-Christian beliefs when almost all of our evidence comes from medieval Christian authors? Is the concept of “Celtic” even a valid one? These and other questions are addressed ably in this short collection of papers by some of the leading scholars in the field of Celtic studies. -

A Guide to Ten of the Best Pictish Symbol Stones in Aberdeenshire

Pictish Symbol Stones The Pictish Period 300 AD – 900 AD MAIDEN STONE ST PETER’S CHURCH, FYVIE As one of the heartlands of the Pictish community, Aberdeenshire is home to a large The origin of the Picts can be found in the tribal society of the Iron Age. Their society was number of the elaborately decorated Symbol Stones for which the Picts are famed – around hierarchical, with a warrior elite and a lower farming class. They lived in Scotland, North of PICARDY STONE 20% of all Pictish stones recorded in Scotland can be found in Aberdeenshire. the Forth and Clyde rivers, between the 4th and 9th Centuries AD, with a particularly strong presence in what is now Aberdeenshire. This can be seen in the frequent occurrence of place The stones, incised or carved in relief, are decorated with a variety of symbols, ranging from names beginning “Pit”, thought to indicate the site of a Pictish settlement, as well as the BRANDSBUTT geometric shapes and patterns, to animals (real and mythical), human figures, objects, evidence from the archaeological record such as Symbol Stones and fortifications. and Christian motifs. Some earlier Pictish stones are also incised with a script known as Ogham, which comprises a pattern of short linear strokes crossing a vertical line. Said to They acquired the name Pict, or Picti, meaning “Painted People”, from the Romans – indeed, have originated around the 4th Century AD, it is an early form of the Irish language. Most much of what is known of the Picts is derived from historical writers from outside of examples of Ogham inscriptions are thought to represent personal names.