Society and Natural Resources in Southeastern Central America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

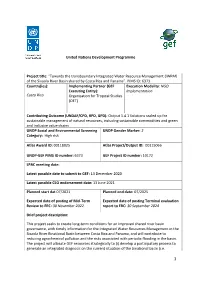

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e. -

1407234* A/HRC/27/52/Add.1

United Nations A/HRC/27/52/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 July 2014 English Original: Spanish Human Rights Council Twenty-seventh session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya Addendum The status of indigenous peoples’ rights in Panama* Summary This report examines the human rights situation of indigenous peoples in Panama on the basis of information gathered by the Special Rapporteur during his visit to the country from 19 to 26 July 2013 and independent research. Panama has an advanced legal framework for the promotion of the rights of indigenous peoples. In particular, the system of indigenous regions (comarcas) provides considerable protection for indigenous rights, especially in terms of land and territory, participation and self-governance, and health and education. National laws and programmes on indigenous affairs provide a vital foundation on which to continue building upon and strengthening the rights of indigenous peoples in Panama. However, the Special Rapporteur notes that this foundation is fragile and unstable in many regards. As discussed in this report, there are a number of problems with regard to the enforcement and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples in Panama, particularly with regard to their right to their lands and natural resources, the implementation of large- scale investment projects, self-governance, participation and their economic and social rights, including the rights to economic development, education and health. In the light of the findings set out in this report, the Special Rapporteur makes specific recommendations to the Government of Panama. -

Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples

Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Santiago, 2021 FAO and FILAC. 2021. Forest governance by indigenous and or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. tribal peoples. An opportunity for climate action in Latin If the work is adapted, then it must be licensed under America and the Caribbean. Santiago. FAO. the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. If a https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953en translation of this work is created, it must include the following disclaimer along with the required citation: The designations employed and the presentation of “This translation was not created by the Food and material in this information product do not imply the Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United this translation. The original English edition shall be the Nations (FAO) or Fund for the Development of the authoritative edition.” Indigenous Peoples of Latina America and the Caribbean (FILAC) concerning the legal or development status of Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or licence shall be conducted in accordance with the concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on The mention of specific companies or products of International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) as at present in force. -

Panama: Land Administration Project (Loan No

Report No. 56565-PA Investigation Report Panama: Land Administration Project (Loan No. 7045-PAN) September 16, 2010 About the Panel The Inspection Panel was created in September 1993 by the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank to serve as an independent mechanism to ensure accountability in Bank operations with respect to its policies and procedures. The Inspection Panel is an instrument for groups of two or more private citizens who believe that they or their interests have been or could be harmed by Bank-financed activities to present their concerns through a Request for Inspection. In short, the Panel provides a link between the Bank and the people who are likely to be affected by the projects it finances. Members of the Panel are selected “on the basis of their ability to deal thoroughly and fairly with the request brought to them, their integrity and their independence from the Bank’s Management, and their exposure to developmental issues and to living conditions in developing countries.”1 The three-member Panel is empowered, subject to Board approval, to investigate problems that are alleged to have arisen as a result of the Bank having failed to comply with its own operating policies and procedures. Processing Requests After the Panel receives a Request for Inspection it is processed as follows: • The Panel decides whether the Request is prima facie not barred from Panel consideration. • The Panel registers the Request—a purely administrative procedure. • The Panel sends the Request to Bank Management, which has 21 working days to respond to the allegations of the Requesters. -

Fish Community Assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers Within the Naso-Teribe Territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible Implications of Bonyic Dam

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2017 Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam. Shaylyn Austin SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Austin, Shaylyn, "Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam." (2017). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2560. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2560 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam. Shaylyn Austin University of Michigan School for International Training: Panama, Spring 2017 1 I. Abstract In the Changuinola/Teribe watershed of Bocas Del Toro, Panama, changes to the fluvial system due to the recently constructed Bonyic Dam have implications connected to the biodiversity of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and the livelihoods of thousands of people of the Naso-Teribe indigenous group. This study investigated the composition of fish communities in 6 study sites in 3 different areas in relation to the Bonyic Dam. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

INDIGENOUS MOBILIZATION, INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND RESISTANCE: THE NGOBE MOVEMENT FOR POLITICAL AUTONOMY IN WESTERN PANAMA By OSVALDO JORDAN-RAMOS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Osvaldo Jordan Ramos 2 A mi madre Cristina por todos sus sacrificios y su dedicacion para que yo pudiera terminar este doctorado A todos los abuelos y abuelas del pueblo de La Chorrera, Que me perdonen por todo el tiempo que no pude pasar con ustedes. Quiero que sepan que siempre los tuve muy presentes en mi corazón, Y que fueron sus enseñanzas las que me llevaron a viajar a tierras tan lejanas, Teniendo la dignidad y el coraje para luchar por los más necesitados. Y por eso siempre seguiré cantando con ustedes, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama a la gente, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama a la gente, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama la gente. Toca el tambor, llama a la gente, Toca la caja, llama a la gente, Toca el acordeón, llama a la gente... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to recognize the great dedication and guidance of my advisor, Philip Williams, since the first moment that I communicated to him my decision to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Florida. Without his encouragement, I would have never been able to complete this dissertation. I also want to recognize the four members of my dissertation committee: Ido Oren, Margareth Kohn, Katrina Schwartz, and Anthony Oliver-Smith. -

Issues Related to the Naso People 30

Report No. 56565-PA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Investigation Report Panama: Land Administration Project Public Disclosure Authorized (Loan No. 7045-PAN) September 16, 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized About the Panel The Inspection Panel was created in September 1993 by the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank to serve as an independent mechanism to ensure accountability in Bank operations with respect to its policies and procedures. The Inspection Panel is an instrument for groups of two or more private citizens who believe that they or their interests have been or could be harmed by Bank-financed activities to present their concerns through a Request for Inspection. In short, the Panel provides a link between the Bank and the people who are likely to be affected by the projects it finances. Members of the Panel are selected “on the basis of their ability to deal thoroughly and fairly with the request brought to them, their integrity and their independence from the Bank’s Management, and their exposure to developmental issues and to living conditions in developing countries.”1 The three-member Panel is empowered, subject to Board approval, to investigate problems that are alleged to have arisen as a result of the Bank having failed to comply with its own operating policies and procedures. Processing Requests After the Panel receives a Request for Inspection it is processed as follows: • The Panel decides whether the Request is prima facie not barred from Panel consideration. • The Panel registers the Request—a purely administrative procedure. • The Panel sends the Request to Bank Management, which has 21 working days to respond to the allegations of the Requesters. -

Rough Draft for Southern Mesoamerica Assessment

Assessing Five Years of CEPF Investment in the Mesoamerica Biodiversity Hotspot Southern Mesoamerica A Special Report April 2007 CONTENTS Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 3 CEPF 5-Year Logical Framework Reporting................................................................................ 21 Appendices .................................................................................................................................... 29 2 OVERVIEW The Mesoamerica Hotspot encompasses some of the most biologically diverse habitat in the world. While it consistently ranks among the top five hotspots for animal diversity and endemism, it also ranks among the most threatened. To address these threats, the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) invested $5.5 million from 2002 to 2006 in the three biologically richest corridors in the southern half of the hotspot: • Cerro Silva – La Selva Corridor in Costa Rica and Nicaragua; • Osa Corridor in Costa Rica; and • Talamanca – Bocas del Toro Corridor in Costa Rica and Panama. CEPF is a joint initiative of Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the government of Japan, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and Cerro Silva – the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to La Selva engage nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), community groups, and other sectors of civil society in biodiversity conservation. Within the Mesoamerica Hotspot, the three Talamanca -

The Indigenous World-2003

1 • • • • • • • • • • 2 • • • • • • • • 3 • • 2003 Copenhagen • • IWGIA • • • • • WORLD 2002-2003 WORLD THE INDIGENOUS THE THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2002-2003 Compilation and editing: Diana Vinding Regional editors: The Circumpolar North & North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Mexico, Central America & the Circumcaribbean: Diana Vinding South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Diana Vinding Asia: Christian Erni and Sille Stidsen Middle East: Diana Vinding Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen Indigenous Rights: Lola García-Alix Cover, typesetting and maps: Jorge Monrás English translation: Elaine Bolton English proofreading: Elaine Bolton & Birgit Stephenson Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISSN 0105-4503 ISBN 87-90730-74-7 © The authors and IWGIA (International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs), 2003 - All Rights Reserved. The reproduction and distribution of information contained in The Indigenous World is welcome as long as the source is cited. However, the reproduction of the whole BOOK should not occur without the consent of IWGIA. The opinions expressed in this publica- tion do not necessarily reflect those of the International Work Group. The Indigenous World is published annually in English and Spanish by IWGIA Director: Jens Dahl Deputy Director: Lola García-Alix Administrator: Karen Bundgaard Andersen This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS -

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Domestic Arrangements for Recording Reports, and Prohibited Acts and Expressions

United Nations CERD/C/SR.1994 International Convention on Distr.: General 7 September 2010 the Elimination of All Forms English of Racial Discrimination Original: French Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Seventy-sixth session Summary record of the 1994th meeting Held at the Palais Wilson, Geneva, on Tuesday, 2 March 2010, at 10 a.m. Chairperson: Mr. Kemal Contents Consideration of reports, comments and information submitted by States parties under article 9 of the Convention (continued) Fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth periodic reports of Panama (continued) This record is subject to correction. Corrections should be submitted in one of the working languages. They should be set forth in a memorandum and also incorporated in a copy of the record. They should be sent within one week of the date of this document to the Editing Unit, room E.4108, Palais des Nations, Geneva. Any corrections to the records of the public meetings of the Committee at this session will be consolidated in a single corrigendum, to be issued shortly after the end of the session. GE.10-40960 (E) 030810 070910 CERD/C/SR.1994 The meeting was called to order at 10.10 a.m. Consideration of reports, comments and information submitted by States parties under article 9 of the Convention (continued) Fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth periodic reports of Panama (continued) (CERD/C/PAN/15-20; CERD/C/PAN/Q/15-20 and Add.1; HRI/CORE/1/Add.14/Rev.1) 1. At the invitation of the Chairperson, the members of the delegation of Panama took places at the Committee table. -

The Indigenous World2013

IWGIA THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2013 This yearbook contains a comprehensive update on the current situation of indigenous peoples and their human THE INDIGENOUS WORLD rights, and provides an overview of the most important developments in international and regional processes during 2012. THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2013 In 67 articles, indigenous and non-indigenous scholars and activists provide their insight and knowledge to the book with country reports covering most of the indig- enous world, and updated information on international and regional processes relating to indigenous peoples. The Indigenous World 2013 is an essential source of information and indispensable tool for those who need to be informed about the most recent issues and de- velopments that have impacted on indigenous peoples worldwide. 2013 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS 3 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2013 Copenhagen 2013 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2013 Compilation and editing: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Regional editors: Arctic & North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Mexico, Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Diana Vinding and Cæcilie Mikkelsen Asia: Christian Erni and Christina Nilsson The Middle East: Diana Vinding Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen and Geneviève Rose International Processes: Lola García-Alix and Kathrin Wessendorf Cover and typesetting: Jorge Monrás Maps: Jorge Monrás English translation: Elaine Bolton and Lindsay Green-Barber Proof reading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark © The authors and The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), 2013 - All Rights Reserved HURRIDOCS CIP DATA The reproduction and distribution of information contained Title: The Indigenous World 2013 in The Indigenous World is welcome as long as the source Edited by: Cæcilie Mikkelsen is cited. -

53-Management Response

MANAGEMENT RESPONSE TO REQUESTS FOR INSPECTION PANEL REVIEW OF THE PANAMA LAND ADMINISTRATION PROJECT (Loan No. 7045-PAN) Management has reviewed the two Requests for Inspection of the Panama Land Administration Project (Loan No. 7045-PAN), the first received by the Inspection Panel on February 25, 2009 and registered on March 11, 2009 (RQ 09/01), and the second received on March 17, 2009 and registered on March 20, 2009 (RQ 09/04). Management has prepared the following response. Panama CONTENTS Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Terms ............................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. v I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 II. THE REQUESTS ..................................................................................................... 2 The First Request .................................................................................................... 2 The Second Request ................................................................................................ 2 III. CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 3 Management’s Broader Engagement with Panama ................................................ 3 Panama’s Efforts in Land Administration .............................................................. 4 Origins of Conflict .................................................................................................