Power, Environment, and Indigenous Peoples in a Globalizing Panama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Floating Doctors Volunteer Handbook

Volunteer Handbook 1 Last Update 2016_07_30 Table of Contents 1. Floating Doctors a. Mission Statement b. Goals 2. Scope of Work a. Mobile Clinics b. Mobile Imaging c. Public Health Research d. Health Education e. Professional Training f. Patient Chaperoning g. Ethnomedicine h. Asilo i. Community Projects 3. Pre-Arrival Information a. Bocas del Toro b. Packing List c. Traveling to Bocas del Toro d. Arrival in Bocas 4. Volunteer Policies a. Work Standards b. Crew Code of Ethics and Conduct 5. Health and Safety a. Purpose b. Staying Healthy c. Safety Considerations 6. Financial Guidelines a. Volunteer Contributions b. Floating Doctors Contributions c. Personal Expenses 7. On-Site Logistics a. Community Guidelines b. Curfew c. Keys d. Laundry e. Resources f. Recycling 8. Living in Bocas a. Floating Doctors Discounts b. Groceries c. Restaurants d. Internet e. Phone 9. Basic Weekly Schedule a. Typical Weekly Schedule b. What to Expect on a Clinic Day c. What to Expect on a Multi-Day Clinic 10. Phone List 2 Last Update 2016_07_30 I. Floating Doctors Mission Statement The Floating Doctors’ ongoing mission is to reduce the present and future burden of disease in the developing world, and to promote improvements in health care delivery worldwide. Goals Our goals include: 1. Providing free acute and preventative health care services and delivering donated medical supplies to isolated areas. 2. Reducing child and maternal mortality through food safety/prenatal education, nutritional counseling and clean water solutions. 3. Studying and documenting local systems of health care delivery and identifying what progress have been made, what challenges remain, and what solutions exist to improve health care delivery worldwide. -

Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations

Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations Mark P. Sullivan Specialist in Latin American Affairs November 27, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30981 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations Summary With five successive elected civilian governments, the Central American nation of Panama has made notable political and economic progress since the 1989 U.S. military intervention that ousted the regime of General Manuel Antonio Noriega from power. Current President Ricardo Martinelli of the center-right Democratic Change (CD) party was elected in May 2009, defeating the ruling center-left Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in a landslide. Martinelli was inaugurated to a five-year term on July 1, 2009. Martinelli’s Alliance for Change coalition with the Panameñista Party (PP) also captured a majority of seats in Panama’s National Assembly. Panama’s service-based economy has been booming in recent years – with a growth rate of 7.6% in 2010 and 10.6% in 2011 – largely because of the ongoing Panama Canal expansion project, now slated for completion in early 2015. The CD’s coalition with the PP fell apart at the end of August 2011when President Martinelli sacked PP leader Juan Carlos Varela as Foreign Minister. Varela, however, retains his position as Vice President. Tensions between the CD and the PP had been growing throughout 2011, largely related to which party would head the coalition’s ticket for the 2014 presidential election. Despite the breakup of the coalition, the strength of the CD has grown significantly since 2009 because of defections from the PP and the PRD and it now has a majority on its own in the legislature. -

Panama Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Panama This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Panama. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Panama 3 Key Indicators Population M 4.0 HDI 0.788 GDP p.c., PPP $ 23015 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.6 HDI rank of 188 60 Gini Index 51.0 Life expectancy years 77.8 UN Education Index 0.708 Poverty3 % 7.0 Urban population % 66.9 Gender inequality2 0.457 Aid per capita $ 2.2 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary The election and the beginning of the mandate of Juan Carlos Varela in July 2014 meant a return to political normality for the country, which had experienced a previous government under President Martinelli (2009-2014) characterized by a high perception of corruption and authoritarian tendencies in governance. -

Financing Plan, Which Is the Origin of This Proposal

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT FACILITY REQUEST FOR PIPELINE ENTRY AND PDF-B APPROVAL AGENCY’S PROJECT ID: RS-X1006 FINANCINGIDB PDF* PLANIndicate CO-FINANCING (US$)approval 400,000date ( estimatedof PDFA ) ** If supplemental, indicate amount and date GEFSEC PROJECT ID: GEFNational ALLOCATION Contribution 60,000 of originally approved PDF COUNTRY: Costa Rica and Panama ProjectOthers (estimated) 3,000,000 PROJECT TITLE: Integrated Ecosystem Management of ProjectSub-Total Co-financing PDF Co- 960,000 the Binational Sixaola River Basin (estimated)financing: 8,500,000 GEF AGENCY: IDB Total PDF Project 960,000 OTHER EXECUTING AGENCY(IES): Financing:PDF A* DURATION: 8 months PDF B** (estimated) 500,000 GEF FOCAL AREA: Biodiversity PDF C GEF OPERATIONAL PROGRAM: OP12 Sub-Total GEF PDF 500,000 GEF STRATEGIC PRIORITY: BD-1, BD-2, IW-1, IW-3, EM-1 ESTIMATED STARTING DATE: January 2005 ESTIMATED WP ENTRY DATE: January 2006 PIPELINE ENTRY DATE: November 2004 RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: Ricardo Ulate, GEF Operational Focal Point, 02/27/04 Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE), Costa Rica Ricardo Anguizola, General Administrator of the 01/13/04 National Environment Authority (ANAM), Panama This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for approval. IA/ExA Coordinator Henrik Franklin Janine Ferretti Project Contact Person Date: November 8, 2004 Tel. and email: 202-623-2010 1 [email protected] PART I - PROJECT CONCEPT A - SUMMARY The bi-national Sixaola river basin has an area of 2,843.3 km2, 19% of which are in Panama and 81% in Costa Rica. -

Crecimiento Económico Sin Equidad Agudiza Contradicciones Sociales

Análisis de coyuntura – marzo de 2008. Panamá: Crecimiento económico sin equidad agudiza contradicciones sociales Los ajustes económicos y la represión selectiva han hecho sentir sus efectos en Panamá a principios de 2008 recrudeciendo los movimientos reivindicativos en los sectores laborales así como en las comunidades cuyo medios de vida son amenazados por las políticas gubernamentales. Los trabajadores de la construcción así como los empleados públicos del sector social (educación y salud) y las comunidades afectadas por proyectos ajenos a plan de desarrollo alguno, como los mineros, las hidroeléctricas y turísticos han redoblado sus protestas contra el neoliberalismo. El gobierno y los inversionistas, sin embargo, se felicitan por la tasa de crecimiento anual del producto interno bruto que promedia el 10 por ciento. Este incremento, que el mismo gobierno no puede explicar, se suma al “boom” de la construcción y a las expectativas creadas por la ampliación del Canal de Panamá. El país, por su lado, sigue con el 40 por ciento de las familias por debajo de la línea de pobreza, el 46 por ciento de los trabajadores en el sector informal y con los indicadores de inequidad aumentando. Para coronar la situación, el gobierno se encuentra agobiado por acusaciones de corrupción que afectan todos los niveles públicos y privados. La Autoridad del Canal de Panamá (ACP) anunció que tanto en 2007 como 2008 los tránsitos disminuirán significativamente. La tendencia es consecuencia de la crisis económica de EEUU que disminuyó las importaciones del exterior. La desaceleración del movimiento marítimo afectará los ingresos por peajes del Canal. Elecciones de 2009 Las contradicciones se agudizan faltando poco más de un año (mayo de 2009) para celebrarse las elecciones generales. -

Political Careers, Corruption, and Impunity

Political careers, corruPtion, and imPunity Panama’s assembly, 1984 – 2009 carlos Guevara mann University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana © 2011 University of Notre Dame Introduction The scene could have hardly been more illustrative of this book’s topic. On January 16, 2002, before a crowd of cameramen and reporters, Pana - manian legislator Carlos Afú, then of Partido Revolucionario Demo - crático (PRD),1 extracted a stack of paper money from his jacket. Those six thousand dollars, he said, were the first installment of a payment for his vote in favor of a multimillion-dollar contract between the govern- ment of Panama and a private consortium, Centro Multimodal Indus- trial y de Servicios (CEMIS).2 Legislator Afú claimed to have received the money from fellow party and assembly member Mateo Castillero, chair- man of the chamber’s Budget Committee. Disbursement of the bribe’s balance—US$14,000—was still pending. That was the only kickback he had received, claimed Afú, alluding to the accusation of another fel- low party and assembly member, Balbina Herrera,3 that Afú had received “suitcases filled with money” to approve the appointment of two gov- ernment nominees to the Supreme Court. Afú’s declarations sent shock waves throughout the country and seemed to confirm the perception of Panama’s political system as one in which corruption, impunity, and clientelism prevail. As political figures exchanged accusations and added more sleaze to the story, commenta- tors, media, and civil society organizations called for a sweeping inves- tigation of the “Afúdollars” case. But the tentacles of the CEMIS affair 1 © 2011 University of Notre Dame 2 | Political Careers, Corruption, and Impunity were spread too broadly throughout Panama’s political establishment. -

Socioeconomic Characterization of Bocas Del Toro in Panama: an Application of Multivariate Techniques

Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional G&DR. V. 16, N. 3, P. 59-71, set-dez/2020. Taubaté, SP, Brasil. ISSN: 1809-239X Received: 11/14/2019 Accepted: 04/26/2020 SOCIOECONOMIC CHARACTERIZATION OF BOCAS DEL TORO IN PANAMA: AN APPLICATION OF MULTIVARIATE TECHNIQUES CARACTERIZACIÓN SOCIOECONÓMICA DE BOCAS DEL TORO EN PANAMÁ: UNA APLICACIÓN DE TÉCNICAS MULTIVARIADAS Barlin Orlando Olivares1 Jacob Pitti2 Edilberto Montenegro3 Abstract The objective of this work was to identify the main socioeconomic characteristics of the villages with an agricultural vocation in the Bocas del Toro district, Panama, through multivariate techniques. The two principal components that accounted for 84.0% of the total variation were selected using the Principal Components Analysis. This allowed a classification in three strata, discriminating the populated centers of greater agricultural activity in the district. The study identified that the factors with the greatest impact on the characteristics of the population studied were: the development of agriculture in indigenous territories, the proportion of economically inactive people and economic occupation other than agriculture; This characterization serves as the first approach to the study of sustainable land management in indigenous territories. Keywords: Applied Economy, Biodiversity, Crops, Multivariate Statistics, Sustainability. Resumen El objetivo de este trabajo fue identificar las principales características socioeconómicas de los poblados con vocación agrícola del distrito Bocas del Toro, Panamá, a través de técnicas multivariadas. Mediante el Análisis de Componentes Principales se seleccionaron los primeros dos componentes que explicaban el 84.0 % de la variación total. Esto permitió una clasificación en tres estratos, discriminando los centros poblados de mayor actividad agrícola en el distrito. -

1 Bocas Del Toro Cauchero Esc

CALENDARIO DE BECA UNIVERSAL Y PLANILLA GLOBAL TERCERA ENTREGA 2019 DIRECCIÓN PROVINCIAL DE BOCAS DEL TORO 23 DE OCTUBRE DE 2019 Nº DISTRITO CORREGIMIENTO CENTRO EDUCATIVO 1 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE DIONISIA G. DE AYARZA 2 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE LAS PIÑAS 3 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE QUEBRADA EL BAJO 4 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE QUEBRADA LIMÓN 5 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE RAMBALA RAMBALA 6 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE RAMBALA CHIRIQUICITO # 1 7 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE RAMBALA CHIRIQUICITO # 2 8 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE RAMBALA CENTRO BET-EL 9 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE RAMBALA NUEVA ESTRELLA 10 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA PEÑA I.P.T CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE 11 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA PEÑA C.E.B.G. PUNTA PEÑA 12 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA PEÑA CAÑAZAS 13 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE MIRAMAR MIRAMAR 14 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE MIRAMAR ALTO LA GLORIA 15 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE MIRAMAR LAS CAÑAS 16 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE MIRAMAR LOS MOLEJONES 17 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE MIRAMAR LOS CHIRICANOS 18 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA ROBALO PALMA REAL 19 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA ROBALO VALLE SECO 20 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA ROBALO PUNTA ROBALO 21 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE PUNTA ROBALO LA CONGA 22 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE BAJO CEDRO C.E.B.G. BAJO CEDRO 23 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE BAJO CEDRO QUEBRADA GARZA 24 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE BAJO CEDRO ALTO CEDRO 25 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE BAJO CEDRO C.E.B.G. RÍO AUYAMA 26 CHIRIQUÍ GRANDE BAJO CEDRO EL ESCOBAL 24 DE OCTUBRE DE 2019 Nº DISTRITO CORREGIMIENTO CENTRO EDUCATIVO 1 BOCAS DEL TORO CAUCHERO ESC. CAUCHERO ARRIBA 2 BOCAS DEL TORO CAUCHERO ESC. LOS HIGUERONES 3 BOCAS DEL TORO CAUCHERO ESC. LOMA AZUL 4 BOCAS DEL TORO CAUCHERO ESC. LOMA ESTRELLA 5 BOCAS DEL TORO CAUCHERO ESC. -

Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S

Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations Mark P. Sullivan Specialist in Latin American Affairs July 15, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30981 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations Summary With five successive elected civilian governments, the Central American nation of Panama has made notable political and economic progress since the 1989 U.S. military intervention that ousted the regime of General Manuel Noriega from power. The current President, Ricardo Martinelli of the centrist Democratic Change (CD) party was elected in May 2009, defeating the ruling Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in a landslide. Martinelli was inaugurated to a five- year term on July 1, 2009. His Alliance for Change coalition also captured a majority of seats in Panama’s National Assembly that will increase the chances that the new President will be able to secure enough votes to enact his legislative agenda. One of the most significant challenges facing the Martinelli government is dealing with the economic fallout stemming from the global economic recession. Panama’s service-based economy had been booming in recent years, largely because of the Panama Canal expansion project, but the global financial crisis and the related decline in U.S. import demand stemming from the U.S. recession has begun to slow Panama’s economic growth. During the presidential campaign, Martinelli pledged to simplify the tax system by the introduction of a flat tax in order to discourage tax evasion. He also has called for a number of large public infrastructure projects, including a subway system for Panama City, a light rail system on the outskirts of Panama City, regional airports and roads, and a third bridge over the Canal. -

Bocas Del Toro Mission

Image not found or type unknown Bocas Del Toro Mission DOMINGO RAMOS SANJUR Domingo Ramos Sanjur, B.A. in Theology (Adventist University of Central America, Alajuela, Costa Rica), is the president of Bocas del Toro Mission. Previously, he was a pastor and area coordinator in Bocas del Toro. He is married to Ruth Luciano and has three children. Bocas del Toro Mission is an administrative unit of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Panama. It is a part of Panama Union Mission in the Inter-American Division of Seventh-day Adventists. Territory and Statistics Bocas del Toro is a province of Panama with Bocas del Toro as its capital city. As of 2018, it had an area of 45,843.90 km2 and a population of 170,320 inhabitants.1 It shares borders with the Caribbean Sea to the north, the province of Chiriquí to the south, the indigenous region of Ngöbe Buglé to the east and southeast, the province of Limón in Costa Rica to the west and northwest, and the province of Puntarenas in Costa Rica to the southwest. Bocas del Toro Mission has 30 churches, 4,272 members, and a population of 127,414. Its offices are on Avenida 17 de Abril in El Empalme, Changuinola, Bocas del Toro, Panama. Its territory includes the Bocas del Toro province and the Nio Cribo region, which itself includes Kankintú and Kusapín. It is a part of Panama Union Mission of the Inter- American Division.2 Bocas del Toro Mission also has 28 groups, two schools, one high school, three ordained ministers, and six licensed ministers as of 2018. -

Cacao, the Guaymi and Reforestation in Western Panama

NGÖBE CULTURAL VALUES OF CACAO AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN WESTERN PANAMA by JEFFREY JAMES STOIKE (Under the Direction of Carl F. Jordan) ABSTRACT This thesis examines questions of conservation and development pertaining to the Ngöbe, an indigenous group in western Panama, with a focus on cacao (Theobroma cacao Linn.) agroforestry. A political ecology framework is applied to cacao agroforestry as sustainable development amongst the Ngöbe in a historical context. Through research based on both academic and grey literature, as well as an unpublished thesis, I discuss Ngöbe symbolic values of cacao in the context of conservation and development trends in the region. I make specific reference to the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC), a transnational conservation program which promotes cacao agroforestry in Ngöbe communities. I conclude that future conservation efforts should be directed towards the development of policies that enhance broader Ngöbe values for cacao and should not rely overwhelmingly on market-based criteria. INDEX WORDS: cacao, agroforestry, sustainable development, Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, Bocas del Toro, Panama, Ngöbe. NGÖBE CULTURAL VALUES OF CACAO AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN WESTERN PANAMA by JEFFREY JAMES STOIKE BA, University of California Berkeley, 1999 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Jeffrey James Stoike All Rights Reserved NGÖBE CULTURAL VALUES OF CACAO AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN WESTERN PANAMA by JEFFREY JAMES STOIKE Major Professor: Carl F. Jordan Committee: Julie Velásquez Runk Paul Sutter Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have assisted in the production of this thesis, an unconventional process from start to finish. -

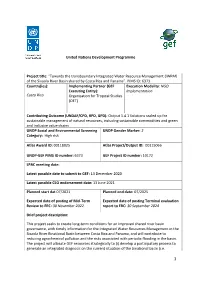

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e.