Prisma Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

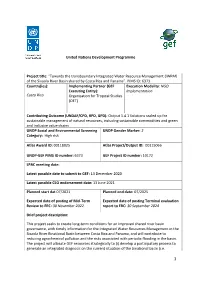

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e. -

1407234* A/HRC/27/52/Add.1

United Nations A/HRC/27/52/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 July 2014 English Original: Spanish Human Rights Council Twenty-seventh session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya Addendum The status of indigenous peoples’ rights in Panama* Summary This report examines the human rights situation of indigenous peoples in Panama on the basis of information gathered by the Special Rapporteur during his visit to the country from 19 to 26 July 2013 and independent research. Panama has an advanced legal framework for the promotion of the rights of indigenous peoples. In particular, the system of indigenous regions (comarcas) provides considerable protection for indigenous rights, especially in terms of land and territory, participation and self-governance, and health and education. National laws and programmes on indigenous affairs provide a vital foundation on which to continue building upon and strengthening the rights of indigenous peoples in Panama. However, the Special Rapporteur notes that this foundation is fragile and unstable in many regards. As discussed in this report, there are a number of problems with regard to the enforcement and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples in Panama, particularly with regard to their right to their lands and natural resources, the implementation of large- scale investment projects, self-governance, participation and their economic and social rights, including the rights to economic development, education and health. In the light of the findings set out in this report, the Special Rapporteur makes specific recommendations to the Government of Panama. -

Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples

Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Forest governance by indigenous and tribal peoples An opportunity for climate action in Latin America and the Caribbean Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Santiago, 2021 FAO and FILAC. 2021. Forest governance by indigenous and or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. tribal peoples. An opportunity for climate action in Latin If the work is adapted, then it must be licensed under America and the Caribbean. Santiago. FAO. the same or equivalent Creative Commons license. If a https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2953en translation of this work is created, it must include the following disclaimer along with the required citation: The designations employed and the presentation of “This translation was not created by the Food and material in this information product do not imply the Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United this translation. The original English edition shall be the Nations (FAO) or Fund for the Development of the authoritative edition.” Indigenous Peoples of Latina America and the Caribbean (FILAC) concerning the legal or development status of Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or licence shall be conducted in accordance with the concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on The mention of specific companies or products of International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) as at present in force. -

Panama: Land Administration Project (Loan No

Report No. 56565-PA Investigation Report Panama: Land Administration Project (Loan No. 7045-PAN) September 16, 2010 About the Panel The Inspection Panel was created in September 1993 by the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank to serve as an independent mechanism to ensure accountability in Bank operations with respect to its policies and procedures. The Inspection Panel is an instrument for groups of two or more private citizens who believe that they or their interests have been or could be harmed by Bank-financed activities to present their concerns through a Request for Inspection. In short, the Panel provides a link between the Bank and the people who are likely to be affected by the projects it finances. Members of the Panel are selected “on the basis of their ability to deal thoroughly and fairly with the request brought to them, their integrity and their independence from the Bank’s Management, and their exposure to developmental issues and to living conditions in developing countries.”1 The three-member Panel is empowered, subject to Board approval, to investigate problems that are alleged to have arisen as a result of the Bank having failed to comply with its own operating policies and procedures. Processing Requests After the Panel receives a Request for Inspection it is processed as follows: • The Panel decides whether the Request is prima facie not barred from Panel consideration. • The Panel registers the Request—a purely administrative procedure. • The Panel sends the Request to Bank Management, which has 21 working days to respond to the allegations of the Requesters. -

Fish Community Assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers Within the Naso-Teribe Territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible Implications of Bonyic Dam

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2017 Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam. Shaylyn Austin SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Austin, Shaylyn, "Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam." (2017). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2560. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2560 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fish community assessment of the Bonyic and Teribe Rivers within the Naso-Teribe territory Bocas Del Toro, Panama: Possible implications of Bonyic Dam. Shaylyn Austin University of Michigan School for International Training: Panama, Spring 2017 1 I. Abstract In the Changuinola/Teribe watershed of Bocas Del Toro, Panama, changes to the fluvial system due to the recently constructed Bonyic Dam have implications connected to the biodiversity of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and the livelihoods of thousands of people of the Naso-Teribe indigenous group. This study investigated the composition of fish communities in 6 study sites in 3 different areas in relation to the Bonyic Dam. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

INDIGENOUS MOBILIZATION, INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND RESISTANCE: THE NGOBE MOVEMENT FOR POLITICAL AUTONOMY IN WESTERN PANAMA By OSVALDO JORDAN-RAMOS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Osvaldo Jordan Ramos 2 A mi madre Cristina por todos sus sacrificios y su dedicacion para que yo pudiera terminar este doctorado A todos los abuelos y abuelas del pueblo de La Chorrera, Que me perdonen por todo el tiempo que no pude pasar con ustedes. Quiero que sepan que siempre los tuve muy presentes en mi corazón, Y que fueron sus enseñanzas las que me llevaron a viajar a tierras tan lejanas, Teniendo la dignidad y el coraje para luchar por los más necesitados. Y por eso siempre seguiré cantando con ustedes, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama a la gente, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama a la gente, Aje Vicente, toca la caja y llama la gente. Toca el tambor, llama a la gente, Toca la caja, llama a la gente, Toca el acordeón, llama a la gente... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to recognize the great dedication and guidance of my advisor, Philip Williams, since the first moment that I communicated to him my decision to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Florida. Without his encouragement, I would have never been able to complete this dissertation. I also want to recognize the four members of my dissertation committee: Ido Oren, Margareth Kohn, Katrina Schwartz, and Anthony Oliver-Smith. -

Ethnicity at Work Divided Labor on a Central American Banana Plantation

Ethnicity at Work Divided Labor on a Central American Banana Plantation Philippe I. Bourgois The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore and London Johns Hopkins Studies in Atlantic History and Culture Richard Price, Series Editor r e c e n t a n d r e l a t e d t it l e s in t h e s e r ie s Main Currents in Caribbean Thought: The Historical Evolution of Caribbean Society in Its Ideological Aspects, 1492-1900 Gordon K. Lewis The Man-of-Words in the West Indies: Performance and the Emergence of Creole Culture Roger D. Abrahams First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People Richard Price Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807-1834 B. W. Higman Between Slavery and Free Labor: The Spanish-Speaking Caribbean in the Nineteenth Century edited by Manuel Moreno Fraginals, Frank Moya Pons, and Stanley Engerman Caribbean Contours edited by Sidney W. Mintz and Sally Price Bondmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua, with Implications for Colonial British America David Barry Gaspar The Ambiguities of Dependence in South Africa: Class, Nationalism, and the State in Twentieth-Century Natal Shula Marks Peasants and Capital: Dominica in the World Economy Michel-Rolph Trouillot Kingdom and Colony: Ireland in the Atlantic World, /560-/S00 Nicolas Canny This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation ©1989 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The Johns Hopkins University Press, 701 West 40th Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21211 The Johns Hopkins Press Ltd., London The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, a n s i Z39.48-1984. -

The Indigenous World 2018

THE INDIGENOUS WORLD THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2018 Copenhagen THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2018 Compilation and editing: Pamela Jacquelin-Andersen Regional editors: Arctic and North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Mexico, Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Diana Vinding Asia: Signe Leth The Middle East: Diana Vinding Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen and Geneviève Rose International Processes: Lola García-Alix and Kathrin Wessendorf Cover and typesetting: Spine Studio Maps and layout: Neus Casanova Vico English translation: Elaine Bolton, Rebecca Knight and Madeline Newman Ríos Proofreading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark Cover photographies: Pablo Toranzo/Andhes, Christian Erni, Delphine Blast, Nelly Tokmagasheva and Thomas Skielboe HURIDOCS CIP DATA © The authors and The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs Title: The Indigenous World 2018 (IWGIA), 2018 All Rights Reserved Edited by: Pamela Jacquelin-Andersen Pages: 640 ISSN: 1024-0217 The reproduction and distribution of information con- ISBN: 978-87-92786-85-2 tained in The Indigenous World is welcome as long as the source is cited. However, the translation of articles Language: English into other languages and the of the whole BOOK is not Index: 1. Indigenous Peoples – 2. Yearbook – 3. allowed without the consent of IWGIA. The articles in The Indigenous World are pro- International Processes duced on a voluntary basis. It is IWGIA’s intention that BISAC codes: LAW110000 Indigenous Peoples The Indigenous World should provide a comprehensive update on the situation of indigenous peoples world- REF027000 Yearbooks & Annuals POL035010 wide but, unfortunately, it is not always possible to find Political Freedom & Security / Human Rights authors to cover all relevant countries. -

Issues Related to the Naso People 30

Report No. 56565-PA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Investigation Report Panama: Land Administration Project Public Disclosure Authorized (Loan No. 7045-PAN) September 16, 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized About the Panel The Inspection Panel was created in September 1993 by the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank to serve as an independent mechanism to ensure accountability in Bank operations with respect to its policies and procedures. The Inspection Panel is an instrument for groups of two or more private citizens who believe that they or their interests have been or could be harmed by Bank-financed activities to present their concerns through a Request for Inspection. In short, the Panel provides a link between the Bank and the people who are likely to be affected by the projects it finances. Members of the Panel are selected “on the basis of their ability to deal thoroughly and fairly with the request brought to them, their integrity and their independence from the Bank’s Management, and their exposure to developmental issues and to living conditions in developing countries.”1 The three-member Panel is empowered, subject to Board approval, to investigate problems that are alleged to have arisen as a result of the Bank having failed to comply with its own operating policies and procedures. Processing Requests After the Panel receives a Request for Inspection it is processed as follows: • The Panel decides whether the Request is prima facie not barred from Panel consideration. • The Panel registers the Request—a purely administrative procedure. • The Panel sends the Request to Bank Management, which has 21 working days to respond to the allegations of the Requesters. -

The Protection of Forest Biodiversity Can Conflict with Food Access for Indigenous People

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, September 27, 2016, IP: 129.79.203.191] Conservation and Society 14(3): 279-290, 2016 Article The Protection of Forest Biodiversity can Conflict with Food Access for Indigenous People Olivia Sylvestera,b,#, Alí García Segurac, and Iain J. Davidson-Hunta aDepartment of Environment, Development, and Peace, Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada bUniversity for Peace, Ciudad, Colón, San José, Costa Rica cEscuela de Filología, Lingüística y Literatura, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica #Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract International protected area (PA) management policies recognise the importance of respecting Indigenous rights. However, little research has been conducted to evaluate how these policies are being enforced. We evaluated whether Indigenous rights to access traditional food were being respected in La Amistad Biosphere Reserve, Costa Rica. By examining land management documents, we found that PA regulations have the potential to restrict traditional food access because these regulations ban shifting agriculture and heavily restrict hunting; these regulations do not address the harvest of edible plants. By working with Bribri people, we found multiple negative impacts that PAs had on: health, nutrition, passing on cultural teachings to youth, quality of life, cultural identity, social cohesion and bonding, as well as on the land and non-human beings. We propose three steps to better support food access in PAs in Costa Rica and elsewhere. First, a right to food framework should inform PA management regarding traditional food harvesting. Second, people require opportunities to define what harvesting activities are traditional and sustainable and these activities should be respected in PA management. -

Rough Draft for Southern Mesoamerica Assessment

Assessing Five Years of CEPF Investment in the Mesoamerica Biodiversity Hotspot Southern Mesoamerica A Special Report April 2007 CONTENTS Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 3 CEPF 5-Year Logical Framework Reporting................................................................................ 21 Appendices .................................................................................................................................... 29 2 OVERVIEW The Mesoamerica Hotspot encompasses some of the most biologically diverse habitat in the world. While it consistently ranks among the top five hotspots for animal diversity and endemism, it also ranks among the most threatened. To address these threats, the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) invested $5.5 million from 2002 to 2006 in the three biologically richest corridors in the southern half of the hotspot: • Cerro Silva – La Selva Corridor in Costa Rica and Nicaragua; • Osa Corridor in Costa Rica; and • Talamanca – Bocas del Toro Corridor in Costa Rica and Panama. CEPF is a joint initiative of Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the government of Japan, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and Cerro Silva – the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to La Selva engage nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), community groups, and other sectors of civil society in biodiversity conservation. Within the Mesoamerica Hotspot, the three Talamanca -

THE INDIGENOUS WORLD-2006.Indd

THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2006 Copenhagen 2006 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2006 Compilation and editing: Sille Stidsen Regional editors: The Circumpolar North & North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacifi c: Sille Stidsen and Jens Dahl Asia: Christian Erni and Sille Stidsen Middle East: Diana Vinding and Sille Stidsen Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen International Processes: Lola García-Alix Cover, typesetting and maps: Jorge Monrás English translation and proof reading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISSN 1024-0217 - ISBN 87-91563-18-6 © The authors and IWGIA (The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs), 2006 - All Rights Reserved The reproduction and distribution of information contained in The Indigenous World is welcome as long as the source is cited. However, the reproduction of the whole BOOK should not occur without the consent of IWGIA. The opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily refl ect those of the International Work Group. The Indigenous World is published annually in English and Spanish by The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. Director: Jens Dahl Deputy Director: Lola García Alix Administrator: Anni Hammerlund Distribution in North America: Transaction Publishers 390 Campus Drive / Somerset, New Jersey 08873 www.transactionpub.com This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, NORAD, Sida and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax: (45) 35 27 05 07 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.iwgia.org CONTENTS Editorial ....................................................................................................