Encoding “The Capital” in Edo Encoder « La Capitale» À Edo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: the Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya Jqzaburô (1751-97)

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya JQzaburô (1751-97) Yu Chang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 0 Copyright by Yu Chang 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtm Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OnawaOFJ KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence diowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Publishing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Pubüsher Tsutaya Jûzaburô (1750-97) Master of Arts, March 1997 Yu Chang Department of East Asian Studies During the ideologicai program of the Senior Councillor Mitsudaira Sadanobu of the Tokugawa bah@[ governrnent, Tsutaya JÛzaburÔ's aggressive publishing venture found itseif on a collision course with Sadanobu's book censorship policy. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

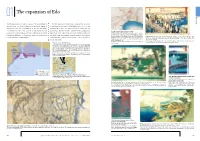

01 the Expansion Of

The expansion of Edo I ntroduction With Tokugawa Ieyasu’s entry to Edo in 1590, development of In 1601, construction of the roads connecting Edo to regions the castle town was advanced. Among city construction projects around Japan began, and in 1604, Nihombashi was set as the undertaken since the establishment of the Edo Shogunate starting point of the roads. This was how the traffic network government in 1603 is the creation of urban land through between Edo and other regions, centering on the Gokaido (five The five major roads and post towns reclamation of the Toshimasusaki swale (currently the area from major roads of the Edo period), were built. Daimyo feudal lords Post towns were born along the five major roads of the Edo period, with post stations which provided lodgings and ex- Nihombashi Hamacho to Shimbashi) using soil generated by and middle- and lower-ranking samurai, hatamoto and gokenin, press messengers who transported goods. Naito-Shinjuku, Nihombashi Shinsen Edo meisho Nihon-bashi yukibare no zu (Famous Places in Edo, leveling the hillside of Kandayama. gathered in Edo, which grew as Japan’s center of politics, Shinagawa-shuku, Senju-shuku, and Itabashi-shuku were Newly Selected: Clear Weather after Snow at Nihombashi Bridge) From the collection of the the closest post towns to Edo, forming the general periphery National Diet Library. society, and culture. of Edo’s built-up area. Nihombashi, which was set as the origin of the five major roads (Tokaido, Koshu-kaido, Os- Prepared from Ino daizu saishikizu (Large Colored Map by hu-kaido, Nikko-kaido, Nakasendo), was bustling with people. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Art Spotlight: Hokusai's Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fiji

Art Spotlight: Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji This document has all 36 prints from Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji. The following links will help you discuss these works with your children. • Art Spotlight: Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji: The original blog post about these works with commentary, discussion questions, and learning activities • Woodblock Printing with Kids tutorial • Free Art Appreciation Printable Worksheet Bundle • How to Look at Art with Children • All art posts on the Art Curator for Kids The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ Conventions of Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints • peaceful, harmonious scenes • asymmetrical composition • limited color palette of about 4 colors plus black • unclear space or perspective • diagonal or curved lines that guide your eye through the composition • outlined shapes filled with solid, flat color The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ Questions to Ask • What is going on in this artwork? What do you see that makes you say that? • What emotions do you feel when looking at this artwork? What emotions do you think the artist was feeling? • Describe the lines and colors in this artwork. How do the colors and lines contribute to the emotion? • Describe the ways Hokusai included Mount Fuji in the artworks. • What can you tell about the Japanese way of life in the Edo Period by looking at these artworks? What types of things are the people doing? • What do these artworks have in common? How could you tell that these were created by Hokusai during this time period? The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ Learning Activities 1. -

The Basic Structure of Tanka Prose

The Elements of Tanka Prose by Jeffrey Woodward Introduction: Basic Definition The marriage of prose and waka, the forerunner of modern tanka, occurred early in the history of Japanese literature, from the 8th to 11th centuries, with rudimentary beginnings in the Man’yōshū and later elaboration as an art in the Tales of Ise and Tale of Genji. One aspect of the proliferation of prose with waka forms is that practice moved far in advance of theory. Japanese criticism to this day lacks consensus on a name for this hybrid genre. The student, instead, is met with a plethora of terms that aspire to be form-specific, e.g., preface or headnote (kotobagaki), poem tale (uta monogatari), literary diary (nikki bungaku), travel account (kikō), poetic collection (kashū), private poetry collection (shikashū) and many more [Konishi, II, 256-258; Miner, 14-16] The first problem one must address, therefore, in any discussion of tanka plus prose is terminology. While Japanese waka practice and criticism afford no precedent, the analogy of tanka with prose to the latter development of haibun does. The term haibun, when applied to a species of literary composition, commonly signifies haiku plus prose written in the ―haikai spirit.‖ It would not be mere license to replace haibun with haiku prose or haikai prose as proper nomenclature. Upon the same grounds, tanka prose becomes a reasonable term to apply to literary specimens that incorporate tanka plus prose – a circumstance which may lead one to inquire, not unreasonably, whether tanka prose also indicates prose composed in the ―tanka spirit.‖ Fundamental Structure of Tanka Prose Tanka prose, like haibun, combines the two modes of writing: verse and prose. -

Learning from SHOGUN

Learning from Shǀgun Japanese History and Western Fantasy Edited by Henry Smith Program in Asian Studies University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California 93106 Contents Designed by Marc Treib Contributors vi Copyright © 1980 by Henry D. Smith II Maps viii for the authors Preface xi Distributed by the Japan Society, 333 East 47th Street, New York, Part I: The Fantasy N.Y. 10017 1 James Clavell and the Legend of the British Samurai 1 Henry Smith 2 Japan, Jawpen, and the Attractions of an Opposite 20 Illustrations of samurai armor are David Plath from Murai Masahiro, Tanki yǀryaku 3 Shǀgun as an Introduction to Cross-Cultural Learning 27 (A compendium for the mounted Elgin Heinz warrior), rev. ed., 1837, woodblock edition in the Metropolitan Museum Part II: The History of Art, New York 4 Blackthorne’s England 35 Sandra Piercy 5 Trade and Diplomacy in the Era of Shǀgun 43 Ronald Toby 6 The Struggle for the Shogunate 52 Henry Smith 7 Hosokawa Gracia: A Model for Mariko 62 Chieko Mulhern This publication has been supported by Part III: The Meeting of Cultures grants from: 8 Death and Karma in the World of Shǀgun 71 Consulate General of Japan, Los William LaFleur Angeles 9 Learning Japanese with Blackthorne 79 Japan-United States Susan Matisoff Friendship Commission 10 The Paradoxes of the Japanese Samurai 86 Northeast Asia Council, Henry Smith Association for Asian Studies 11 Consorts and Courtesans: The Women of Shǀgun 99 USC-UCLA Joint East Asia Henry Smith Studies Center 12 Raw Fish and a Hot Bath: Dilemmas of Daily Life 113 Southern California Conference on Henry Smith International Studies Who’s Who in Shǀgun 127 Glossary 135 For Further Reading 150 Postscript: The TV Transformation 161 vi Contributors vii Sandra Piercy is a graduate student in English history of the Tudor- Stuart period at the University of California, Santa Barbara. -

Biblio:Basho-27S-Haiku.Pdf

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Matsuo Basho¯, 1644–1694. [Poems. English. Selections] Basho¯’s haiku : selected poems by Matsuo Basho¯ / translated by David Landis Barnhill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6165-3 — 0-7914-6166-1 1. Haiku—Translations into English. 2. Japanese poetry—Edo period, 1600–1868—Translations into English. I. Barnhill, David Landis. II. Title. PL794.4.A227 2004 891.6’132—dc22 2004005954 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Basho¯’s Haiku Selected Poems by Matsuo Basho¯ Matsuo Basho¯ Translated by, annotated, and with an Introduction by David Landis Barnhill STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS for Phyllis Jean Schuit spruce fir trail up through endless mist into White Pass sky Contents Preface ix Selected Chronology of the Life of Matsuo Basho¯ xi Introduction: The Haiku Poetry of Matsuo Basho¯ 1 Translation of the Hokku 19 Notes 155 Major Nature Images in Basho¯’s Hokku 269 Glossary 279 Bibliography 283 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Translation 287 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Japanese 311 Index of Names 329 vii Preface “You know, Basho¯ is almost too appealing.” I remember this remark, made quietly, offhand, during a graduate seminar on haiku poetry. -

The History of Law in Japan, Through Historical Sources Murakami Kazuhiro & Nishimura Yasuhiro Eds. Translated and Interpret

The History of Law in Japan, Through Historical Sources Murakami Kazuhiro & Nishimura Yasuhiro eds. Translated and Interpreted by Dan Sherer Lecture 3: The Judicial Formulary of 1232 and Medieval Law Traditionally, schoolchildren in Japan have been taught that the Kamakura shogunate began in 1192, when Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-99) was appointed Barbarian-subduing Generalissimo (seii taishōgun, hereafter “shogun”) by the monarch’s court. Lately, however, the trend has been to teach 1185, the year when Yoritomo defeated the Ise Taira, defeated and killed his brother Minamoto no Yoshitsune, and appointed the first military governors and land stewards. Other possibilities have also been put forward as well, including the year Yoritomo raised troops against the Taira in Izu and entered Kamakura (1180), the year that the Taira escaped westward and Go-Shirakawa gave his official imprimatur to Yoritomo’s rule in the east (1183), and the year of Yoritomo’s appointment as Captain of His Majesty’s Inner Palace Guards of the Right (1190). The beginning of the “Kamakura shogunate” is ambiguous. In Japanese schools the focus is on military governance, which began with Yoritomo as the shogun in Kamakura and the initiator of 1 warrior government—the shogunate—that endured until the modern period (the third shogunate, that of the Tokugawa shoguns, was disestablished in 1868). Setting its beginning in 1192, in contrast, emphasizes longer term shogunate-court relations that are vital to understanding medieval Japanese history. According to this narrative, military organization allowed Yoritomo to succeed in the Gempei Wars (1180-85). The houseman (gokenin) and land steward (jitô) systems, as the foundations of the shogunal lord-and-retainer relationship, were subsequently enabled by the relationship between the Kyoto court and the Kamakura shogunal government. -

![Tokugawa Bakufu Political System [Encyclopedia Entry] Michael Wert Marquette University, Michael.Wert@Marquette.Edu](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9660/tokugawa-bakufu-political-system-encyclopedia-entry-michael-wert-marquette-university-michael-wert-marquette-edu-2589660.webp)

Tokugawa Bakufu Political System [Encyclopedia Entry] Michael Wert Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-2013 Tokugawa Bakufu Political System [Encyclopedia Entry] Michael Wert Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Tokugawa Bakufu Political System," in Japan at War: An Encyclopedia by Louis G. Perez, Editor. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO/Greenwood, 2013: 433-434. Publisher link. © 2013 by ABC-Clio, LLC. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC, Santa Barbara, CA. Tokugawa Bakufu Political System I 433 States for a possible end to its trade embargo Further Reading with Japan while simultaneously preparing Browne, Courtney. Tojo: The Last Banzai. New the nation for war. "If Japan's hundred mil York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1967. lions merge and go forward," he declared, Butow, Robert J. C. Tojo and the Coming of "wars can be won with ease." When it the War. Stanford, CA: Stanford University became apparent that U.S. President Franklin Press, 1969. D. Roosevelt would not rescind his demand Coox, Alvin D. Tojo. New York: Ballantine for a Japanese evacuation of China, Tojo Books, 1975. authorized the navy to ,attack U.S. military Hoyt, Edwin Palmer. Warlord: TojO against installations in Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, the World. Lanham, MD: Scarborough and elsewhere in December 1941. House, 1993. The initial phase of World War II in the Pacific was characterized by a lightning Tokugawa Bakufu Political series of Japanese victories over British and System U.S. forces. These successes boosted Tojo's prestige at home and led to greater accep The Tokugawa bakufu political system tance of his views on the legitimacy of represented a mixture of pre-Tokugawa sho force. -

Encyclopedia of Japanese History

An Encyclopedia of Japanese History compiled by Chris Spackman Copyright Notice Copyright © 2002-2004 Chris Spackman and contributors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License.” Table of Contents Frontmatter........................................................... ......................................5 Abe Family (Mikawa) – Azukizaka, Battle of (1564)..................................11 Baba Family – Buzen Province............................................... ..................37 Chang Tso-lin – Currency............................................... ..........................45 Daido Masashige – Dutch Learning..........................................................75 Echigo Province – Etō Shinpei................................................................ ..78 Feminism – Fuwa Mitsuharu................................................... ..................83 Gamō Hideyuki – Gyoki................................................. ...........................88 Habu Yoshiharu – Hyūga Province............................................... ............99 Ibaraki Castle – Izu Province..................................................................118 Japan Communist Party – Jurakutei Castle............................................135 -

Development and Dispersal Process of Ancient Japanese Clan

Development and Dispersal Process of Ancient Japanese Clan Development and Dispersal Process of Ancient Japanese Clan Masanobu SUZUKI Abstract In ancient Japan, how did the Yamato Kingdom (大和政権) form? In order to research this question, I studied the Ōmiwa clan (大神氏). This clan served the Yamato Kingdom and took charge of religious services in ancient times. The clan was one of the most powerful ancient Japanese clans. Therefore, knowledge of how the imperial family and the Ōmiwa clan are related is indispensable for understanding the nature of the politics of the Yamato Kingdom. Furthermore, it is indispensable for understanding the process of forming the Japanese nation in ancient times. In this paper, I extracted place names, Shinto shrine names, and clan names related to the “Miwa” (神, 三輪) or “Ōmiwa” (大神, 大三輪) from ancient historical documents. I found that they were distributed throughout almost all of the islands in ancient Japan, and some of the clans overlapped geographically. If we now find a related place name or Shinto shrine name, it is likely that related people who the Ōmiwa clan controlled lived there in ancient times. The Yamato Kingdom sent troops to or advanced into western and eastern Japan or foreign countries, so ancient people learned about the Ōmiwa god (大三輪神). They then established shrines for worship- ing that god as a war god, and the Miwa clan (神氏), the Miwahito clan (神人氏), the Miwahitobe clan (神人部 氏), and the Miwabe clan (神部氏) were established in various places in Japan to worship the god according to the local ruling systems of the Yamato Kingdom, including the Hito system (人制), the Bemin system (部民制), and the Kokuzō system (国造制).