Development and Dispersal Process of Ancient Japanese Clan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real-Life Kantei-Of Swords , Part 10: a Real Challenge : Kantei Wakimono Swords

Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho 1) Introduction Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others. Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school. Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. There is also a theory that the school was founded around the Oei era as two branches, one following a smith named Fuji from the Kyushu area and other following a smith named Yasuyoshi from the Kyoto area (who is also said to be the son of Taro Ujiyoshi). -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi No Kumi (Confraria De Misericórdia)

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi no Kumi (Confraria de Misericórdia) Takashi GONOI Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo Introduction During the 80-year period starting when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier and his party arrived in Kagoshima in August of 1549 and propagated their Christian teachings until the early 1630s, it is estimated that a total of 760,000 Japanese converted to Chris- tianity. Followers of Christianity were called “kirishitan” in Japanese from the Portu- guese christão. As of January 1614, when the Tokugawa shogunate enacted its prohibi- tion of the religion, kirishitan are estimated to have been 370,000. This corresponds to 2.2% of the estimated population of 17 million of the time (the number of Christians in Japan today is estimated at around 1.1 million with Roman Catholics and Protestants combined, amounting to 0.9% of total population of 127 million). In November 1614, 99 missionaries were expelled from Japan. This was about two-thirds of the total number in the country. The 45 missionaries who stayed behind in hiding engaged in religious in- struction of the remaining kirishitan. The small number of missionaries was assisted by brotherhoods and sodalities, which acted in the missionaries’ place to provide care and guidance to the various kirishitan communities in different parts of Japan. During the two and a half centuries of harsh prohibition of Christianity, the confraria (“brother- hood”, translated as “kumi” in Japanese) played a major role in maintaining the faith of the hidden kirishitan. An overview of the state of the kirishitan faith in premodern Japan will be given in terms of the process of formation of that faith, its actual condition, and the activities of the confraria. -

The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection

NEWS RELEASE November, 2009 The Lineage of Culture – The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection The Tokyo National Museum is pleased to present the special exhibition “The Lineage of Culture—The Hosokawa Family Eisei Bunko Collection” from Tuesday, April 20, to Sunday, June 6, 2010. The Eisei Bunko Foundation was established in 1950 by 16th-generation family head Hosokawa Moritatsu with the objective of preserving for future generations the legacy of the cultural treasures of the Hosokawa family, lords of the former Kumamoto domain. It takes its name from the “Ei” of Eigen’an—the subtemple of Kenninji in Kyoto, which served as the family temple for eight generations from the time of the original patriarch Hosokawa Yoriari, of the governing family of Izumi province in the medieval period— and the “Sei” of Seiryūji Castle, which was home to Hosokawa Fujitaka (better known as Yūsai), the founder of the modern Hosokawa line. Totaling over 80,000 objects, it is one of the leading collections of cultural properties in Japan and includes archival documents, Yūsai’s treatises on waka poetry, tea utensils connected to the great tea master Sen no Rikyū from the personal collection of 2nd-generation head Tadaoki (Sansai), various objects associated with Hosokawa Gracia, and paintings by Miyamoto Musashi. The current exhibition will present the history of the Hosokawa family and highlight its role in the transmission of traditional Japanese culture—in particular the secrets to understanding the Kokinshū poetry collection, and the cultural arts of Noh theater and the Way of Tea—by means of numerous treasured art objects and historical documents that have been safeguarded through the family’s tumultuous history. -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

Real-Life Kantei of Swords Part 10

Japanese Swords Society of the United States - Volume 48 No. 4 _______________________________________________________________________________ Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho 1) Introduction Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others. Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school. Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages by Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University)

Vegetables and the Diet of the Edo Period, Part 2 Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages By Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University) Introduction compiled by Tomita Iyahiko and completed in 1873, describes the geography and culture of Hida During the Edo period (1603–1868), the number of province. It contains records from 415 villages in villages in Japan remained fairly constant with three Hida counties, including information on land roughly 63,200 villages in 1697 and 63,500 140 years value, number of households, population and prod- later in 1834. According to one source, the land ucts, which give us an idea of the lifestyle of these value of an average 18th and 19th century village, with villagers at the end of the Edo period. The first print- a population of around 400, was as much as 400 to ed edition of Hidago Fudoki was published in 1930 500 koku1, though the scale and character of each vil- (by Yuzankaku, Inc.), and was based primarily on the lage varied with some showing marked individuality. twenty-volume manuscript held by the National In one book, the author raised objections to the gen- Archives of Japan. This edition exhibits some minor eral belief that farmers accounted for nearly eighty discrepancies from the manuscript, but is generally percent of the Japanese population before and during identical. This article refers primarily to the printed the Edo period. Taking this into consideration, a gen- edition, with the manuscript used as supplementary eral or brief discussion of the diet in rural mountain reference. -

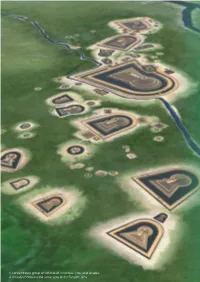

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

What Is Dewa Sanzan? the Spiritual Awe-Inspiring Mountains in the Tohoku Area, Embracing Peopleʼs Prayers… from the Heian Period, Mt.Gassan, Mt.Yudono and Mt

The ancient road of Dewa Rokujurigoegoe Kaido Visit the 1200 year old ancient route! Sea of Japan Yamagata Prefecture Tsuruoka City Rokujurigoe Kaido Nishikawa Town Asahi Tourism Bureau 60-ri Goe Kaido Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture The Ancient Road “Rokujuri-goe Kaido” Over 1200 years, this road has preserved traces of historical events “Rokujuri-goe Kaido,” an ancient road connecting the Shonai plain and the inland area is said to have opened about 1200 years ago. This road was the only road between Shonai and the inland area. It was a precipitous mountain road from Tsuruoka city to Yamagata city passing over Matsune, Juo-toge, Oami, Sainokami-toge, Tamugimata and Oguki-toge, then going through Shizu, Hondoji and Sagae. It is said to have existed already in ancient times, but it is not clear when this road was opened. The oldest theory says that this road was opened as a governmental road connecting the Dewa Kokufu government which was located in Fujishima town (now Tsuruoka city) and the county offices of the Mogami and Okitama areas. But there are many other theories as well. In the Muromachi and Edo periods, which were a time of prosperity for mountain worship, it became a lively road with pilgrims not only from the local area,but also from the Tohoku Part of a list of famous places in Shonai second district during the latter half of the Edo period. and Kanto areas heading to Mt. Yudono as “Oyama mairi” (mountain pilgrimage) custom was (Stored at the Native district museum of Tsuruoka city) booming. -

Island Narratives in the Making of Japan: the Kojiki in Geocultural Context

Island Studies Journal, Ahead of print Island narratives in the making of Japan: The Kojiki in geocultural context Henry Johnson University of Otago [email protected] Abstract: Shintō, the national religion of Japan, is grounded in the mythological narratives that are found in the 8th-Century chronicle, Kojiki 古事記 (712). Within this early source book of Japanese history, myth, and national origins, there are many accounts of islands (terrestrial and imaginary), which provide a foundation for comprehending the geographical cosmology (i.e., sacred space) of Japan’s territorial boundaries and the nearby region in the 8th Century, as well as the ritualistic significance of some of the country’s islands to this day. Within a complex geocultural genealogy of gods that links geography to mythology and the Japanese imperial line, land and life were created along with a number of small and large islands. Drawing on theoretical work and case studies that explore the geopolitics of border islands, this article offers a critical study of this ancient work of Japanese history with specific reference to islands and their significance in mapping Japan. Arguing that a characteristic of islandness in Japan has an inherent connection with Shintō religious myth, the article shows how mythological islanding permeates geographic, social, and cultural terrains. The discussion maps the island narratives found in the Kojiki within a framework that identifies and discusses toponymy, geography, and meaning in this island nation’s mythology. Keywords: ancient Japan, border islands, geopolitics, Kojiki, mapping, mythology https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.164 • Received July 2020, accepted April 2021 © Island Studies Journal, 2021 Introduction This study interprets the significance of islands in Japanese mythological history.