Multiculturalism and Resurgence at a Metis Cultural Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

Chapters in Canadian Popular Music

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Ilona Šoukalová Chapters in Canadian Popular Music Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Chapters in Canadian Popular Music (Diplomová práce) Autor: Ilona Šoukalová Studijní obor: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Počet stran: 72 Počet znaků: 138 919 Olomouc 2015 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma "Chapters in Canadian Popular Music" vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 3.5.2015 Ilona Šoukalová Děkuji vedoucímu mé diplomové práce panu Mgr. Jiřímu Flajšarovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Poděkování patří také pracovníkům Ústřední knihovny Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci za pomoc při obstarávání pramenů a literatury nezbytné k vypracování diplomové práce. Děkuji také své rodině a kamarádům za veškerou podporu v době mého studia. Abstract The diploma thesis deals with the emergence of Canadian popular music and the development of music genres that enjoyed the greatest popularity in Canada. A significant part of the thesis is devoted to an investigation of conditions connected to the relation of Canadian music and Canadian sense of identity and uniqueness. Further, an account of Canadian radio broadcasting and induction of regulating acts which influenced music production in Canada in the second half of the twentieth century are given. Moreover, the effectiveness and contributions of these regulating acts are summarized and evaluated. Last but not least, the main characteristics of the music style of a female singer songwriter Joni Mitchell are examined. -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

Backgroundfile-83687.Pdf

Attachment TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Grants Impact Analysis ........................................................................................... 1 Overview Strategic Funding .................................................................................................................. 3 Arts Discipline Funding ......................................................................................................... 3 Assessment and Allocations Process ................................................................................... 4 Loan Fund ............................................................................................................................. 4 Operations ............................................................................................................................. 4 Preliminary Results of Increased Grants Funding ............................................................................. 6 2014 Allocations Summary ................................................................................................................ 7 Income Statement & Program Balances for the quarter ended December 31, 2014 ........................ 8 Strategic Funding 2014 Partnership Programs .......................................................................................................... 9 Strategic Partnerships ........................................................................................................... 10 Strategic Allocations ............................................................................................................. -

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ______

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ A Knowledge and Literature Review Prepared for the Research and Evaluaon Sec@on Canada Council for the Arts _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE TRÉPANIER & CHRIS CREIGHTON-KELLY December 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For more information, please contact: Research and Evaluation Section Strategic Initiatives 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566‐4414 / (800) 263‐5588 ext. 4261 [email protected] Fax (613) 566‐4430 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e Cette publication est aussi offerte en français Cover image: Hanna Claus, Skystrip(detail), 2006. Photographer: David Barbour Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review ISBN 978‐0‐88837‐201‐7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS! 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY! 4 Why a Literature Review?! 4 Steps Taken! 8 Two Comments on Terminology! 9 Parlez-vous français?! 10 The Limits of this Document! 11 INTRODUCTION! 13 Describing Aboriginal Arts! 15 Aboriginal Art Practices are Unique in Canada! 16 Aboriginal Arts Process! 17 Aboriginal Art Making As a Survival Strategy! 18 Experiencing Aboriginal Arts! 19 ABORIGINAL WORLDVIEW! 20 What is Aboriginal Worldview?! 20 The Land! 22 Connectedness! -

Virtual Program Is Brought to You by the Streaming Services of Entertainment Engineering Collective

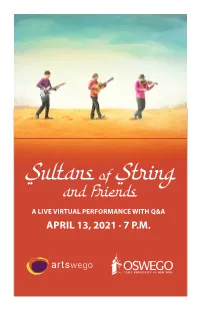

a A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE WITH Q&A APRIL 13, 2021 · 7 P.M. Supporting the Arts at Oswego Made possible by the Student Arts Fee, administered by ARTSwego SUNY Oswego — Livestream interactive Zoom concert! Featured on the New York Times hits list and the Billboard World Music Charts! Sultans of String band members Chris McKhool, Kevin Laliberté and Drew Birston perform the Best of the Sultans, beamed right into your living room! Special guests include Ojibway Elder Duke Redbird, flamenco dancer and singer Tamar Ilana, JUNO Award-winning Hungarian pianist Robi Botos, Madagascar’s Donné Roberts and Yukiko Tsutsui from Japan! This is over Zoom, which is awesome because it is interactive, and we will be able to see and hear you, and you can see and hear us, and you can all see each other as well! It is a real show! So pour yourself a quarantini, and get ready to enjoy the music! The link becomes live at 6:40 p.m. to get settled and chat with our friends. And make sure you have speakers plugged in if you have them! The show will last about an hour, and then will feature a talkback portion, so bring your burning questions, as we will be opening up the floor for anyone who has always wanted to ask any of the artists about their inspiration, or music, or whatever strikes your fancy. Special guest performance by the SUNY Oswego’s Small Group Jazz The Girl from Ipanema Antônio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994) Ryan Zampella, Tenor Saxophone Brandon Schmitt, Guitar Benjamin Coddington, Piano Zachary Robison, Bass Robert Ackerman, Drum Set The State University of New York at Oswego would like to recognize with respect the Onondaga Nation, the “people of the hills,” or central firekeepers of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Indigenous peoples on whose ancestral lands SUNY Oswego now stands. -

ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor: 4.164 Refereed Journal ISSN -2395-1877

IJMDRR Research Paper E- ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor: 4.164 Refereed Journal ISSN -2395-1877 A STUDY OF SYMBOLS AND IMAGERY IN DUKE REDBIRD’S POEM I AM THE REDMAN WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO NORTHROP FRYE’S ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Rajalahshmi T Assistant Professor of English, PG & Research Department of English, Vellalar College for Women, Thindal. Abstract The study of the vast and rich body of the literature of the native people of Canada has been too long neglected and ignored. Very few literary scholars are familiar with the oral literature that transcends the European concepts of genre, or the written literature that spans a wide range of genres-speeches, letters, sermons, reports, petitions, diary entries, essays, history, journals, autobiography, poetry, short stories, and novels. Native poetry of Canada lagged behind prose in the 1970s. Among the poets who managed to get published their poems were Sarain Stump, Duke Redbird, George Kenny, Rita Joe, Ben Abel, Chief Dan George, and Daniel David Moses. Sarain Stump in his poem There is My People Sleeping laments at the loss of the traditional way of life while Duke Redbird in his poem, ‘I Am the Redman’ lashes out against an insensitive white society which reflects the political turmoil of the period when he was a militant social activist. Penne Petrone in her work Native Literature in Canada from the Oral Tradition to the Present has criticized, “In ‘I Am the Redman’ Redbird’s ironic tone and symbolism, derived from an urban and industrialized society, bristle with contempt and pride” (130). The paper aims to compare the symbols occur in ‘I Am the Redman’ with the archetypal symbols found in mythology and literature with special reference to the Canadian critic Northrop Frye’s, Anatomy of Criticism. -

Learning from the Experiences of Indigenous Children in Care Who Have Multiple School Changes As a Result of Placement Disruption

LEARNING FROM THE EXPERIENCES OF INDIGENOUS CHILDREN IN CARE WHO HAVE MULTIPLE SCHOOL CHANGES AS A RESULT OF PLACEMENT DISRUPTION LANDY ANDERSON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATION YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MARCH 2019 © LANDY ANDERSON, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Crown Wards in Ontario change placements 2.6 to 8.6 times (on average) with the provincial average being four times (Contenta, Monsebraaten, Rankin, Bailey & Ng, 2015, p. 20). This means children in care often change schools. The aim of this study is to learn, directly from Indigenous children in care, their experiences of multiple school changes through exploring the rewards and challenges of starting a new school; ways children prepare for a new school; strategies they use to adjust to a new school; and ways the child welfare and education systems can alleviate the impact of multiple school changes. The methods used for this study include focus groups and participant journals. Four overarching themes were identified within the data: Vulnerability, Relationships, Adaptation, and Excitement. This study adds important new knowledge about Indigenous children in care, specifically about their experiences of disruptive school placements. iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the 15 Indigenous youth in care who had the courage to share their private stories of the rewards and challenges of going to a new school. Their commitment to attend the focus groups (for some, travelling up to three hours) to participate in this study is a testament to their strength and dedication to improve the child welfare system in an effort to help other Indigenous children in care who may face similar struggles. -

Alanis Obomsawin 2020 Glenn Gould Prize Laureate

PRICELESS Vol 26 No 3 Alanis Obomsawin 2020 Glenn Gould Prize Laureate NOVEMBER 2020 Concerts, live & livestreamed Record reviews & Listening Room Stories and interviews 2603_Features_new.indd 1 2020-10-28 6:17 PM FOR WHAT IT’S WORTH • CIRC – keep up with reopenings, welcome new partners • SUBS CAMPAIGN – give (someone/yourself) the gift! • BACK ISSUES (ESP. LAST 4) – ask and ye shall receive • STILL IN PRINT!!!! – pass the word, PLEASE. • BUT MORE THAN PRINT – flip-through, HalfTones, blog, web, tweet, like, share • WEEKLY LISTINGS UPDATES – so keep sending them in!! • WE’RE WholeNote media 2603_Features_new.indd 2 2020-10-28 7:17 PM Volume 26 No 3 | November 2020 This picture of Alanis Obomsawin was taken in her office, at ON OUR COVER the National Film Board’s Montreal headquarters on Le Chemin PRICELESS de la Côte-de Liesse, just before they moved to Îlot Balmoral last Vol 26 No 3 summer. Having had the opportunity of working on a three-year project at the National Film Board of Canada, I had the chance to witness Alanis Obomsawin’s presence on an almost daily basis. If you would be passing by her office door you would witness a monumental intellect tirelessly rewriting our history for a better future for all. Unwavering from sunrise till sunset, she humbled ACD2 2736 us all. She is a true architect of change, winning her battles through the mind and heart, with more than fifty films in fifty years. — Stéphan Ballard Alanis Obomsawin “My office holds 50 years of archives, images, and text. I’m 2020 Glenn Gould Prize Laureate now finishing my 53rd film, so you can just imagine the number NOVEMBER 2020 Concerts, live & livestreamed Record reviews & Listening Room Stories and interviews of documents. -

Food, Land and Power: the Emergence of Indigenous Chefs

Dublin Gastronomy Symposium 2018 – Food and Power Food, Land, and Power: The Emergence of Indigenous Chefs and Restaurants in Canada L. Sasha Gora Abstract: Toronto has over 8000 restaurants, and until A year before, the Globe and Mail published an opinion October 2016 only one offered Indigenous cuisine. Now piece by the Toronto Games’ chairman and former Premier there are three more. Why have there been so few of Ontario, David Peterson. The article had the tone and Indigenous restaurants in the past, and what does this volume of a pep rally. Peterson wanted Toronto to get really reveal about the relationship between food, land, and excited because, as Peterson wrote, ‘Never before has Canada political power in a settler country like Canada? This paper hosted a multi-sport event of this size’ (Peterson 2014). His addresses food as both a tool of Canadian colonialism and promises were as large as the games themselves: ‘These of Indigenous resistance. It focuses on political power games will change lives for the better. They will inspire relations behind the representation of Indigenous cuisines. young people, who may not otherwise consider sports, to Although four is still a tiny number for Canada’s largest get in the game, embrace fitness and build confidence’ city, it does show how Indigenous chefs and restaurateurs (Peterson). As Peterson claimed, the stakes were high: ‘[...] are reclaiming foodways and their representations in urban the world will be watching as we showcase this region and centres. Chefs — such as Rich Francis’ ‘Cooking for its incredible diversity and talents’ (Peterson). The article Reconciliation’, who was the first Indigenous contestant on mentioned spectators, from the United States to Brazil, Top Chef Canada and David Wolfman’s 2015 You are Welcome and the excitement Peterson was confident ‘all Canadians’ Food Truck — are using food to take back cultural power. -

OCAD University to Confer Honorary Degrees on Douglas Coupland and Duke Redbird

OCAD University to confer honorary degrees on Douglas Coupland and Duke Redbird (Toronto—May 30, 2013) OCAD University (OCAD U) will present honorary doctorate degrees to artist and author Douglas Coupland and First Nations poet and educator Duke Redbird at the university’s convocation ceremony at Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto on Thursday, June 6. “Our honorary doctorate recipients are reflective of the qualities we want to impart to this year’s graduating class as they seek to make their own impressions in the world,” said Dr. Sara Diamond, OCAD University President and Vice-Chancellor. “Douglas Coupland’s unparalleled creative musings on contemporary society are demonstrative of the creative practice we hope to inspire in our students. As our first Advisor/Mentor in our Indigenous Visual Culture Program, Duke Redbird has helped guide Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, faculty and staff in Indigenous knowledge and artistic practice. We congratulate our 680 graduates, alongside Douglas and Duke, for everything they bring to the world!” Biographies With the publication of his remarkable and prescient 1991 novel Generation X, artist Douglas Coupland became hailed as the voice of his age. Since that important moment in literary and cultural history, the artist and critic has turned his sharp and insightful attention to design, social commentary, journalism, art theory and criticism as well having managed a broad, active and acclaimed studio practice. Indeed, Coupland’s intellectual engagement effortlessly crosses disciplines and categories of cultural production. The author of 14 works of fiction and four works of non-fiction, a designer of clothing and furniture, an artist of immense range and an internationally known cultural figure respected for his powers of observation and analysis, Coupland’s longstanding, indefatigable interest in the minutiae of everyday life is simultaneously a centrally rich critical vein in his work and an extension of his own way of being in the world. -

Indigenous-Voice-Winter2018 4.Pdf

VOLUME 2, Issue 1 contents on the cover Special Reports HOME AWAY FROM HOME 06 Canadian universities providing students with a Frazer Whiteduck dancing and sharing his story with the "Home away from Home". youth of Kashetchewan. RECLAIMING AND CREATING 09 The story of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples early support of Indigenous music. WALKING IN HER MOCCASINS 12 Engaging Indigenous men Features and boys in the prevention of NEW YEARS MESSAGE violence toward women. 05 National Chief Robert Bertrand welcomes the FOR THE RECORD New Year on behalf of the 17 Why archive management Congress of Aboriginal is vital to the Congress of Peoples. Aboriginal Peoples and its constituents. 11 YOUNG LEADERS THE RIGHT START Youth entrepenuer Malcolm 21 Creating healthy and Simon inspiring youth to successful indigenous children create change. through early learning and childcare engagement. THE DANIELS DECISION 19 What is it and what does it CAP PRIORITIES AND mean for you? 23 RESOLUTIONS What's ahead for the Congress of Aborignal Peoples in 2018. THE INDIGENOUS VOICE WINTER 2018 3 remember the faces of those who have Daniels c. Canada. Ils ont discuté des left us or that we have lost. This past méthodes qui doivent définir les relations year, the 150th anniversary of Canada, de travail et entre le Canada et le CPA. significantly raised the national En rapport direct avec le jugement awareness on just how far this country Daniels, le conseil d’administration du needs to go in order to rectify and prevent further violence and tragedy CPA a consacré énormément de temps against our Indigenous women and girls.