Native Studies Audio-Visuals and Other Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

July 22, 196543 Toronto

Volume 24, Number 14 July 22, 196543 Toronto British American Oil Company's Musical Showcase, a half-hour weekly television quiz - and -music program, goes national August 1. Twenty-two Western -Canadian stations are being added to the 31 -strong eastern roster. Other switches, to more elaborate production and all -live prize displays instead of graph- ics, will follow. So will a change to a paid quiz panel. (B-A wants more money fed into customer prizes - less to the on -air panel participants). The oil company's April dealer letter is reported to credit Showcase with pulling close to a million mail entries and in- creasing the rate of B -A credit card applica- tions by 300 per cent since first airing March 28. In the photo (1. to r.) are: Phil Lauson, Foster Advertising (Montreal); Jack Neuss, retail programs director for B -A (and creator of Showcase); George LaFlêche, emcee and singing star; Denny Vaughn, musical director; Peter Lussier, director -producer, and Bob McNicol, Foster Advertising (Toronto). This is baseball? That's what CFCB Radio in Cornerbrook, Newfoundland, and the local CBC Radio employees seem to think. At least they recently played a three -inning grudge match in their outlandish outfits and called it softball - even agreed on a 2-2 tie score once the shenanigans were over. It was all in a good cause - for the local Royal Canadian Legion. Price of admission to the game was set at one forget-me-not (the flower of remem- brance) per customer. Evidently the Legion's `lower sales were helped considerably. -

Chapters in Canadian Popular Music

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Ilona Šoukalová Chapters in Canadian Popular Music Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Chapters in Canadian Popular Music (Diplomová práce) Autor: Ilona Šoukalová Studijní obor: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Počet stran: 72 Počet znaků: 138 919 Olomouc 2015 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma "Chapters in Canadian Popular Music" vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 3.5.2015 Ilona Šoukalová Děkuji vedoucímu mé diplomové práce panu Mgr. Jiřímu Flajšarovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Poděkování patří také pracovníkům Ústřední knihovny Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci za pomoc při obstarávání pramenů a literatury nezbytné k vypracování diplomové práce. Děkuji také své rodině a kamarádům za veškerou podporu v době mého studia. Abstract The diploma thesis deals with the emergence of Canadian popular music and the development of music genres that enjoyed the greatest popularity in Canada. A significant part of the thesis is devoted to an investigation of conditions connected to the relation of Canadian music and Canadian sense of identity and uniqueness. Further, an account of Canadian radio broadcasting and induction of regulating acts which influenced music production in Canada in the second half of the twentieth century are given. Moreover, the effectiveness and contributions of these regulating acts are summarized and evaluated. Last but not least, the main characteristics of the music style of a female singer songwriter Joni Mitchell are examined. -

First Nations Popular Music in Canada: Identity, Politics

FIRST NATIONS POPULAR MUSIC IN CANADA: IDENTITY, POLITICS AND MUSICAL MEANING by CHRISTOPHER ALTON SCALES B.A., University of Guelph, 1990 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Music We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1996 * © Christopher Alton Scales In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of M0S \ C The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date flffoL 3.6 Rqfe DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT In this thesis, First Nations popular music is examined as a polysemic sign (or symbolic form) whose meaning is mediated both socially and politically. Native popular music is a locus for the action of different social forces which interact in negotiating the nature and the meaning of the music. Music is socially meaningful in that it provides a means by which people construct and recognize social and cultural identities. As such, First Nations popular music functions as an emblem of symbolic differentiation between Canadian natives and non-natives. Native pop music plays host to a number of political meanings embedded in this syncretic musical form. -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

Backgroundfile-83687.Pdf

Attachment TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Grants Impact Analysis ........................................................................................... 1 Overview Strategic Funding .................................................................................................................. 3 Arts Discipline Funding ......................................................................................................... 3 Assessment and Allocations Process ................................................................................... 4 Loan Fund ............................................................................................................................. 4 Operations ............................................................................................................................. 4 Preliminary Results of Increased Grants Funding ............................................................................. 6 2014 Allocations Summary ................................................................................................................ 7 Income Statement & Program Balances for the quarter ended December 31, 2014 ........................ 8 Strategic Funding 2014 Partnership Programs .......................................................................................................... 9 Strategic Partnerships ........................................................................................................... 10 Strategic Allocations ............................................................................................................. -

1951 Year Book Canadian Motion Picture Industry

YEAR BOOK CANADIAN MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY Edited by HYE BOSSIN That's high tribute from the men "behind the show." That's what projectionists everywhere are saying about the . The Projectionist's PROJECTOR Sold By GENERAL THEATRE SUPPLY Co. Limited SAINT JOHN MONTREAL TORONTO WINNIPEG VANCOUVER Coast to Coast Theatre Television, Sound & Projection Service LX* 7 everybody's Book Sho>, / I 317 W. 6th - L. A, 900)« 6t :■ fi MA. 3-1032 1921 1951 s4&&ocicitecl Seneca IfecM limited Montreal — Toronto A COMPLETE LABORATORY SERVICE 35 MM — 16 MM CONTACT AND REDUCTION PRINTING COLOUR — BLACK <5, WHITE Producers of • The famous CANADIAN CAMEO Series of theatrical shorts Released in Canadian theatres and throughout the World. • Commercial & non-theatrical Motion Pictures tor Industrial Sales-Training and Consumer use. • Theatre trailers of every description Made to your order or from Stock. • Tailored sound tracks Recorded and synchronized to silent films—16MM or 35 MM. Distributors of Q motion picture cameras, projectors, screens and all types of photographic accessories and supplies through BENOGRAPH, REG'D, a division of ASSOCIATED SCREEN NEWS. "JtatuHuzl Service 'Pkmi (fatet fo (?<KUt i CANADA'S FINEST THEATRE SEATING Kroehler Push Back Chairs, and Chair No, 301 Manufactured and Distributed by CANADIAN THEATRE CHAIR CO. LTD. 40-42 ST. PATRICK ST. TORONTO, CANADA 2 1951 YEAR BOOK CANADIAN MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY FILM PUBLICATIONS of Canada, Ltd, 175 BLOOR ST. EAST TORONTO 5, ONT. CANADA Editor: HYE BOSSIN Assistants: Miss E. Silver and Ben Halter LARGEST INDEPENDENT CONCESSIONAIRES IN CANADA POPCORN, POPCORN EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES, CANDY MACHINES, DRINK MACHINES, CANDY SUPPLIES ★ We Will Build and Operate a Complete Candy Bar Setup CANADIAN AUTOMATIC CONFECTIONS LIMITED 119 SHERBOURNE ST. -

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ______

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ A Knowledge and Literature Review Prepared for the Research and Evaluaon Sec@on Canada Council for the Arts _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE TRÉPANIER & CHRIS CREIGHTON-KELLY December 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For more information, please contact: Research and Evaluation Section Strategic Initiatives 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566‐4414 / (800) 263‐5588 ext. 4261 [email protected] Fax (613) 566‐4430 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e Cette publication est aussi offerte en français Cover image: Hanna Claus, Skystrip(detail), 2006. Photographer: David Barbour Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review ISBN 978‐0‐88837‐201‐7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS! 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY! 4 Why a Literature Review?! 4 Steps Taken! 8 Two Comments on Terminology! 9 Parlez-vous français?! 10 The Limits of this Document! 11 INTRODUCTION! 13 Describing Aboriginal Arts! 15 Aboriginal Art Practices are Unique in Canada! 16 Aboriginal Arts Process! 17 Aboriginal Art Making As a Survival Strategy! 18 Experiencing Aboriginal Arts! 19 ABORIGINAL WORLDVIEW! 20 What is Aboriginal Worldview?! 20 The Land! 22 Connectedness! -

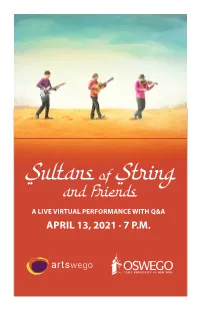

Virtual Program Is Brought to You by the Streaming Services of Entertainment Engineering Collective

a A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE WITH Q&A APRIL 13, 2021 · 7 P.M. Supporting the Arts at Oswego Made possible by the Student Arts Fee, administered by ARTSwego SUNY Oswego — Livestream interactive Zoom concert! Featured on the New York Times hits list and the Billboard World Music Charts! Sultans of String band members Chris McKhool, Kevin Laliberté and Drew Birston perform the Best of the Sultans, beamed right into your living room! Special guests include Ojibway Elder Duke Redbird, flamenco dancer and singer Tamar Ilana, JUNO Award-winning Hungarian pianist Robi Botos, Madagascar’s Donné Roberts and Yukiko Tsutsui from Japan! This is over Zoom, which is awesome because it is interactive, and we will be able to see and hear you, and you can see and hear us, and you can all see each other as well! It is a real show! So pour yourself a quarantini, and get ready to enjoy the music! The link becomes live at 6:40 p.m. to get settled and chat with our friends. And make sure you have speakers plugged in if you have them! The show will last about an hour, and then will feature a talkback portion, so bring your burning questions, as we will be opening up the floor for anyone who has always wanted to ask any of the artists about their inspiration, or music, or whatever strikes your fancy. Special guest performance by the SUNY Oswego’s Small Group Jazz The Girl from Ipanema Antônio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994) Ryan Zampella, Tenor Saxophone Brandon Schmitt, Guitar Benjamin Coddington, Piano Zachary Robison, Bass Robert Ackerman, Drum Set The State University of New York at Oswego would like to recognize with respect the Onondaga Nation, the “people of the hills,” or central firekeepers of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Indigenous peoples on whose ancestral lands SUNY Oswego now stands. -

ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor: 4.164 Refereed Journal ISSN -2395-1877

IJMDRR Research Paper E- ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor: 4.164 Refereed Journal ISSN -2395-1877 A STUDY OF SYMBOLS AND IMAGERY IN DUKE REDBIRD’S POEM I AM THE REDMAN WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO NORTHROP FRYE’S ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Rajalahshmi T Assistant Professor of English, PG & Research Department of English, Vellalar College for Women, Thindal. Abstract The study of the vast and rich body of the literature of the native people of Canada has been too long neglected and ignored. Very few literary scholars are familiar with the oral literature that transcends the European concepts of genre, or the written literature that spans a wide range of genres-speeches, letters, sermons, reports, petitions, diary entries, essays, history, journals, autobiography, poetry, short stories, and novels. Native poetry of Canada lagged behind prose in the 1970s. Among the poets who managed to get published their poems were Sarain Stump, Duke Redbird, George Kenny, Rita Joe, Ben Abel, Chief Dan George, and Daniel David Moses. Sarain Stump in his poem There is My People Sleeping laments at the loss of the traditional way of life while Duke Redbird in his poem, ‘I Am the Redman’ lashes out against an insensitive white society which reflects the political turmoil of the period when he was a militant social activist. Penne Petrone in her work Native Literature in Canada from the Oral Tradition to the Present has criticized, “In ‘I Am the Redman’ Redbird’s ironic tone and symbolism, derived from an urban and industrialized society, bristle with contempt and pride” (130). The paper aims to compare the symbols occur in ‘I Am the Redman’ with the archetypal symbols found in mythology and literature with special reference to the Canadian critic Northrop Frye’s, Anatomy of Criticism. -

CBC Times 490410.PDF

Miss Verna g. Weber, SE:RGE!I. Al tao PRAIRIE REGION SCHEDULE April 10 • 16, 1949 Issued ~ach Week by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation VOLUME n No. IS ISSUED AT WINNIPEG. APRIL I 5c PER COPY-$I.OQ PER YEAR This Week: Holy Week Meditations (Pages 1-3) * St. Matthew Passion (Page 5) * Rossini's Stabat Mater (Page 7) * Cuckoo Clock House ~ THIS IS Mathilda, the obliging bird ot the Cuckoo Clock House. testing her voice for the special Easter edition of the program on April 16. With her are Beth Robinson and Kenny Graham, the two young Torontonian~ who have boon on the popular children's pro gram since it started more than three years ago. Mathilda's cheerful song is heard each week, heralding the program and marking the transi lion from onc "room" of the 'nouse" to another. Cuckoo Clock House is heard on the CBC Dominion network Saturdays at 5:00 p.m. CST, 5:30 p.m. MST. * * * Easter Easter is a time of special delight to young people. Indeed all the symbols associated with it-hot-cross buns. Easter eggs, rabbits, Bowers and new bonnets-suggest new life and reflect the atmosphere of youth and spring. For chil dren and others interested in the folk customs of the festival, Charles Wasserman of Montreal will trace their origin and explain how some of them came to Canada. He will speak on April 16 in the program Thi.l Week. Holy Week Meditations Winnipeg Concert Many other programs during the week will Each day during Holy Week, special quarter The Winnipeg Concert this week (Sunday, have Easter themes. -

Learning from the Experiences of Indigenous Children in Care Who Have Multiple School Changes As a Result of Placement Disruption

LEARNING FROM THE EXPERIENCES OF INDIGENOUS CHILDREN IN CARE WHO HAVE MULTIPLE SCHOOL CHANGES AS A RESULT OF PLACEMENT DISRUPTION LANDY ANDERSON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATION YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MARCH 2019 © LANDY ANDERSON, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Crown Wards in Ontario change placements 2.6 to 8.6 times (on average) with the provincial average being four times (Contenta, Monsebraaten, Rankin, Bailey & Ng, 2015, p. 20). This means children in care often change schools. The aim of this study is to learn, directly from Indigenous children in care, their experiences of multiple school changes through exploring the rewards and challenges of starting a new school; ways children prepare for a new school; strategies they use to adjust to a new school; and ways the child welfare and education systems can alleviate the impact of multiple school changes. The methods used for this study include focus groups and participant journals. Four overarching themes were identified within the data: Vulnerability, Relationships, Adaptation, and Excitement. This study adds important new knowledge about Indigenous children in care, specifically about their experiences of disruptive school placements. iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the 15 Indigenous youth in care who had the courage to share their private stories of the rewards and challenges of going to a new school. Their commitment to attend the focus groups (for some, travelling up to three hours) to participate in this study is a testament to their strength and dedication to improve the child welfare system in an effort to help other Indigenous children in care who may face similar struggles.