NORVAL MORRISSEAU Life & Work by Carmen Robertson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

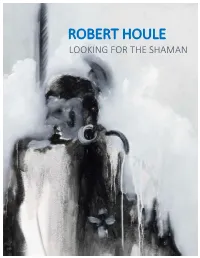

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

CV Photo/Ciel Variable, Montreal, No

A N G E L A G R A U E R H O L Z Recognition and Awards (Visual Arts) 2018 Honorary Doctorate Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver 2017 150 Years of Photography / Canada 150 Commemorative Collection, 2017 Canada Post, Ottawa 2015 Recipient of the Scotiabank Photography Award, Toronto 2014 Recipient of the Governor General Award in Visual and Media Arts, Canada Council for the Arts, Ottawa 2013 Shortlisted for the Scotiabank Photography Award, Toronto 2006 Awarded the Prix Paul-Émile Borduas, Government of Quebec, Quebec Solo exhibitions 2019 The Empty S(h)elf – First iteration, Artexte, Montreal The Book is the Book, installation at the Madras Literary Society (library), 2019 Chennai Photo Biennale, Chennai Angela Grauerholz: Écrins, écrans, McIntosh Gallery, Western University, London, ON 2018 Scotiabank Contact Festival / Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto Art 45, Montréal 2016 Angela Grauerholz (Scotiabank Photography Award), Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto Angela Grauerholz/Écrins, écrans, Canadian Cultural Centre/Centre culturel canadien, Paris 2014 Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto 2012 Art 45, Montreal 2011 Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto Angela Grauerholz: The inexhaustible image…épuiser l’image, University of Toronto Art Centre (UTAC), Toronto 2010 Angela Grauerholz: The inexhaustible image…épuiser l’image, National Gallery of Canada/Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography/Musée canadien de la photographie contemporaine (CMCP), Ottawa (book/catalogue) McMaster Museum of Art, McMaster University, -

Portraits of Aboriginal People by Europeans and by Native Americans

OTHERS AND OURSELVES: PORTRAITS OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE BY EUROPEANS AND BY NATIVE AMERICANS Eliana Stratica Mihail and Zofia Krivdova This exhibition explores portraits of Aboriginal peoples in Canada, from the 18th to the 21st centuries. It is divided thematically into four sections: Early Portraits by European Settlers, Commercially-produced Postcards, Photographic Portraits of Aboriginal Artists, and Portraits of and by Aboriginal people. The first section deals with portraits of Aboriginal people from the 18th to the 19th century made by Europeans. They demonstrate an interest in the “other,” but also, with a few exceptions, a lack of knowledge—or disinterest in depicting their distinct physical features or real life experiences. The second section of the exhibition explores commercially produced portraits of First Nations peoples of British Columbia, which were sold as postcards. These postcards date from the 1920s, which represents a period of commercialization of Native culture, when European-Canadians were coming to British Columbia to visit Aboriginal villages and see totem poles. The third section presents photographic portraits of Aboriginal artists from the 20th century, showing their recognition and artistic realizations in Canada. This section is divided into two parts, according to the groups of Aboriginal peoples the artists belong to, Inuit and First Nations. The fourth section of the exhibition explores portraits of and by Aboriginals. The first section sharply contrasts with the last, showing the huge gap in mentality and vision between European settlers, who were just discovering this exotic and savage “other,” and Native artists, whose artistic expression is more spiritual and figurative. This exhibition also explores chronologically the change in the status of Aboriginal peoples, from the “primitive other” to 1 well-defined individuals, recognized for their achievements and contributions to Canadian society. -

Analyse D'œuvres Du Style Artistique Woodland

TRACES DE PEINTURE ARTIDAVI_VF1_Fiche1 Analyse d’œuvres du style artistique Woodland Norval Morrisseau est considéré comme le père du style artistique Woodland. Au cours des années 1970, il s’est affilié à une coopérative d’artistes, desquels certains ont adopté des aspects de ce langage artistique du style Woodland. Par la suite, il y a eu une relève formée d’une nouvelle génération de peintres qui ont trouvé leur inspiration dans ce style, et ce courant se poursuit encore aujourd’hui. Dans cet exercice, tu exploreras des œuvres de ces deux groupes d’artistes : ceux qui étaient à l’origine, et ceux de la relève. Citation de Daphne Odjig : « Nous sommes un peuple vivant et une culture vivante. Je suis convaincue que notre destin est de progresser, d’expérimenter et de développer de nouveaux modes d’expression, comme le font tous les peuples. Je n’ai pas l’intention de rester figée dans le passé. Je n’suis pas une pièce de musée. » Source : Les dessins et peintures de Daphne Odjig : Une exposition rétrospective, Bonnie Devine, Robert Houle et Duke Redbird, 2007. Consigne Tu analyseras deux œuvres, une de chaque groupe. Les œuvres du premier groupe sont celles d’artistes qui ont côtoyé Norval Morrisseau et comme lui, ont adopté un langage artistique similaire. Leurs couleurs plutôt ternes avec l’ocre très présent rappellent celles des pictogrammes et peintures rupestres sur les rochers dans la région des Grands Lacs où ce style est né. Bien que ces œuvres présentent des ressemblances, le style de plusieurs de ces artistes se transformera dans une forme personnelle, surtout à partir des années 1980, quand on verra émerger l’usage de couleurs éclatantes. -

Knowledge Organiser: How Do Artists Represent Their Environment

Knowledge Organiser: How do Artists represent their environment through painting? Timeline of key events 1972 – Three First Nations artists did a joint exhibition in Winnipeg 1973 – Following the success of the exhibition, three artists plus four more, created Indian Group Of Seven to represent Indian art and give it value and recognition. 1975 – Group disbanded Key Information Artists choose to work in a particular medium and style. They represent the world as they see it. Key Places Winnipeg, Manitoba, Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta Key Figures Daphne Odjig 1919 – 2016 Woodland style, Ontario; moved to British Columbia Alex Janvier 1935 – present Abstract, represent hide-painting, quill work and bead work; Alberta Jackson Beardy 1944 - 1984, Scenes from Ojibwe and Cree oral traditions, focusing on relationships between humans and nature. Manitoba. Eddy Cobiness 1933 – 1996 Life outdoors and nature; born USA moved to winnipeg Norval Morrisseau 1931 – 2007 Woodland stlye; Ontario, also known as Copper Thunderbird Carl Ray 1943 – 1978 Woodland style, electrifying colour (founder member); Ontario Joseph Sanchez 1948 – present Spritual Surrealist; Born USA moved to Manitoba Christi Belcourt 1966 – present Metis visual artist, often paints with dots in the style of Indian beading – Natural World; Ontario Key Skills Drawing and designing: Research First Nations artists. Identify which provinces of Canada they come from. Compare and contrast the works of the different artists. Take inspiration from the seven artists to plan an independent piece of art based on the relevant artist: • Give details (including own sketches) about the style of some notable artists, artisans and designers. • type of paint, brush strokes, tools Symbolic representation • Create original pieces that show a range of influences and styles based on the Indian Group of Seven and their work. -

Chronology of Daphne Odjig's Life: Attachment #1

Chronology of Daphne Odjig’s life: Attachment #1 Excerpt p.p. 137 – 141 The Drawings and Paintings of Daphne Odjig: A Retrospective Exhibition by Bonnie Devine Published by the National Gallery of Canada in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Sudbury, 2007 1919 Born 11 September at Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve, Manitoulin Island, Ontario, the first of four children, to Dominic Odjig and his English war bride Joyce Peachy. Odjig’s widowed grandfather, Jonas Odjig, lives with the family in the house he had built a generation earlier and which still stands in Wikwemikong today. The family is industrious and relatively prosperous by reserve standards. Jonas Odjig is a carver of monuments and tombstones; Dominic is the village constable. The family also farms their land, raises cows, pigs, and chickens and owns a team of horses. 1925 Begins school at Jesuit Mission in Wikwemikong. An avid student, she turns the family’s pig house into a play school where she teaches local children to read and count. When they tire of her instruction she converts the play school into a play church and hears their confessions. The family is musical. Daphne plays the guitar; Dominic the violin. They all enjoy sing-a-longs and music nights listening to a hand-cranked phonograph. She develops a life-long love of opera singing. She is athletic and participates in the annual fall fairs at Manitowaning, the nearest off-reserve town, eight miles away, taking prizes in running and public speaking. Art is her favourite subject and she develops the habit of sketching with her grandfather and father, both of whom are artistic. -

Joker • City Again Battling Province • Impeachment

GREATER HAMILTON’S INDEPENDENT VOICE OCTOBER 10 — 23, 2019 VOL. 25 NO. 39 Preordained JOKER • CITY AGAIN BATTLING PROVINCE • IMPEACHMENT • MORTGAGE RATES • 2 WEEKS OF FREE WILL ASTROLOGY 2 OCTOBER 10 — 23, 2019 VIEW VIEW OCTOBER 10 — 23, 2019 3 READERS’ CHOICE 15 LIAISON COLLEGE GOLD BEST CULINARY COLLEGE SILVER BEST TRADE SCHOOL INSIDE THIS ISSUE OCTOBER 10 — 23, 2019 12 COVER GHOST FORUM THEATRE 05 PERSPECTIVE Impeach Trump 08 REVIEW Love All 05 CATCH 08 REVIEW Much Ado... 15 READERS’ CHOICE 09 REVIEW TDTKTP MOVIES FOOD 28 REVIEW Joker 30 Dining Guide 36 Movie Reviews ETC. MUSIC 37 General Classifieds 12 Hamilton Music Notes 38-39 Free Will Astrology 31 Live Music Listing 39 Adult Classifieds 370 MAIN STREET WEST, HAMILTON, ONTARIO L8P 1K2 HAMILTON 905.527.3343 FAX 905.527.3721 VIEW FOR ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: 905.527.3343 X102 EDITOR IN CHIEF Ron Kilpatrick x109 [email protected] OPERATIONS DIRECTOR CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING ACCOUNTING PUBLISHER Marcus Rosen x101 Liz Kay x100 Roxanne Green x103 Sean Rosen x102 [email protected] 1.866.527.3343 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ADVERTISING DEPT DISTRIBUTION CONTRIBUTORS LISTINGS EDITOR RandA distribution Rob Breszny • Gregory SENIOR CORPORATE Alison Kilpatrick x100 Owner:Alissa Ann latour Cruikshank • Sara Cymbalisty • REPRESENTATIVE [email protected] Manager:Luc Hetu Maxie Dara • Albert DeSantis • Ian Wallace x107 905-531-5564 Darrin DeRoches • Daniel [email protected] HAMILTON MUSIC NOTES [email protected] Gariépy • Allison M. Jones • Tamara Kamermans • Michael Ric Taylor Klimowicz • Don McLean ADVERTISING [email protected] PRINTING • Brian Morton • Ric Taylor • REPRESENTATIVE MasterWeb Printing Michael Terry Al Corbeil x105 PRODUCTION [email protected] [email protected] PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT NO. -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

Chapters in Canadian Popular Music

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Ilona Šoukalová Chapters in Canadian Popular Music Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Chapters in Canadian Popular Music (Diplomová práce) Autor: Ilona Šoukalová Studijní obor: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Počet stran: 72 Počet znaků: 138 919 Olomouc 2015 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma "Chapters in Canadian Popular Music" vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 3.5.2015 Ilona Šoukalová Děkuji vedoucímu mé diplomové práce panu Mgr. Jiřímu Flajšarovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Poděkování patří také pracovníkům Ústřední knihovny Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci za pomoc při obstarávání pramenů a literatury nezbytné k vypracování diplomové práce. Děkuji také své rodině a kamarádům za veškerou podporu v době mého studia. Abstract The diploma thesis deals with the emergence of Canadian popular music and the development of music genres that enjoyed the greatest popularity in Canada. A significant part of the thesis is devoted to an investigation of conditions connected to the relation of Canadian music and Canadian sense of identity and uniqueness. Further, an account of Canadian radio broadcasting and induction of regulating acts which influenced music production in Canada in the second half of the twentieth century are given. Moreover, the effectiveness and contributions of these regulating acts are summarized and evaluated. Last but not least, the main characteristics of the music style of a female singer songwriter Joni Mitchell are examined. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

Overlapping Violent Histories: a Curatorial Investigation Into Difficult Knowledge Curated by Noor Bhangu

Overlapping Violent Histories: A Curatorial Investigation into Difficult Knowledge Curated By Noor Bhangu February 9 - March 9, 2018 Kitchen-Table Discussion: March 8, 12:30-1:30 PM Winnipeg is no stranger to violence or violent histo- heels of such projects, Overlapping Violent Histories: general audience that happens to encounter the work ries. Its geographical position at the heart of Canada A Curatorial Investigation into Difficult Knowledge in the oft-decontextualized setting of the art gallery. and its cultural position as a meeting ground be- brings together the work of Jackson Beardy, Caroline Of course, as a curator of this exhibition I, too, plead tween diverse communities have pushed it to play Dukes, Takao Tanabe, and KC Adams to consider the guilty on counts of decontextualisation by favouring host to the darkest of local, national, and international place of historical trauma in each artist’s practice. In specific elements of a work and leaving out others. currents, including the ongoing colonization of Indig- deliberately drawing on the cross-cultural intersection I take refuge in Luis Camnitzer’s theorization of the enous people, Japanese internment, the settlement between the artists, I aim to build on the potential for curatorial order: “The discourse or thesis of the curator of Icelandic immigrants in Gimli, the influx of Russian visual art and exhibition spaces to function as sites for may contradict the discourse of the artist, because Mennonites and Jewish holocaust survivors in the social-engaged dialogues. the curator extrapolates from the presentation of twentieth century, and the marginalization of Euro- artworks in a way that is not necessarily determined pean immigrants and immigrants of colour.