Indian Art in the 1990S Ryan Rice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

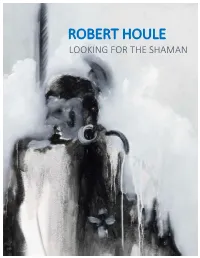

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Chronology of Daphne Odjig's Life: Attachment #1

Chronology of Daphne Odjig’s life: Attachment #1 Excerpt p.p. 137 – 141 The Drawings and Paintings of Daphne Odjig: A Retrospective Exhibition by Bonnie Devine Published by the National Gallery of Canada in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Sudbury, 2007 1919 Born 11 September at Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve, Manitoulin Island, Ontario, the first of four children, to Dominic Odjig and his English war bride Joyce Peachy. Odjig’s widowed grandfather, Jonas Odjig, lives with the family in the house he had built a generation earlier and which still stands in Wikwemikong today. The family is industrious and relatively prosperous by reserve standards. Jonas Odjig is a carver of monuments and tombstones; Dominic is the village constable. The family also farms their land, raises cows, pigs, and chickens and owns a team of horses. 1925 Begins school at Jesuit Mission in Wikwemikong. An avid student, she turns the family’s pig house into a play school where she teaches local children to read and count. When they tire of her instruction she converts the play school into a play church and hears their confessions. The family is musical. Daphne plays the guitar; Dominic the violin. They all enjoy sing-a-longs and music nights listening to a hand-cranked phonograph. She develops a life-long love of opera singing. She is athletic and participates in the annual fall fairs at Manitowaning, the nearest off-reserve town, eight miles away, taking prizes in running and public speaking. Art is her favourite subject and she develops the habit of sketching with her grandfather and father, both of whom are artistic. -

Discursividade E Historicidade Nos Documentários De Alanis Obomsawin

DISCURSIVIDADE E HISTORICIDADE NOS DOCUMENTÁRIOS DE ALANIS OBOMSAWIN. ∗ Luiz Alexandre Pinheiro Kosteczka Introdução. Este texto é fruto das reflexões iniciais do desenvolvimento da dissertação de mestrado intitulada Imagem e a Escrita Da História: Os filmes do Conflito de Oka de Alanis Obomsawin , pesquisa que analisa quatro documentários da extensa produção de Alanis Obomsawin, que, em dias atuais, supera o número de trinta documentos audiovisuais. Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance , My Name is Kahentiiosta , Spudwrench: Kahnawake Man e Rocks at Whiskey Trench integram um grupo de filmes conhecido como “Oka Series”. Essa coleção de documentários originou-se de um conflito entre indígenas e o Estado canadense ocorrido no verão de 1990, no qual as populações dos territórios de Kanehsatake e Kahnawake enfrentaram as autoridades estatais para barrar um projeto de construção civil que adentraria nas reservas das Primeiras-Nações. O primeiro embate iniciou-se quando os indígenas fecharam o acesso ao local designado para o empreendimento imobiliário e turístico. A situação recrudesceu e tornou-se violenta: um tiroteio entre a Sûreté du Québec (Polícia Provincial) e os habitantes de Kanehsatake vitimou fatalmente o agente Marcel Lemay. Em seguida, membros do território vizinho de Kahnawake fecharam a Mercier Bridge. Foi nesse momento que os confrontos ganharam projeção nacional, principalmente pela intervenção militar do exército canadense e pelo início da cobertura jornalística. Nesses desdobramentos, Obomsawin ultrapassou o cerco militar e começou a documentar do lado indígena do conflito, lá permanecendo durante os 78 dias de duração do impasse. As filmagens da realizadora e da sua equipe da L’office National du Film/National Film Board (ONF/NFB), agência canadense de fomento e produção ∗ Mestrando no Programa História e Sociedade da Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP – Campus Assis, orientado pela Prof. -

Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories: Oppositional Looking in Shelley Niro's "This Land is Mime Land" Jennifer Danielle Mccall University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Mccall, Jennifer Danielle, "Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories: Oppositional Looking in Shelley Niro's "This Land is Mime Land"" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4149 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renegotiating Identities, Cultures and Histories: Oppositional Looking in Shelley Niro’s This Land is Mime Land By Jennifer McCall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Art and Art History College of the Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Riccardo Marchi, Ph.D. Elisabeth Fraser, Ph.D. Sara Crawley, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 28, 2012 Keywords: Contemporary art, Canada, photography, feminist, Native American Copyright © 2012, Jennifer McCall ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Riccardo Marchi, Dr. Elisabeth Fraser and Dr. Sara Crawley for all of their support and guidance over the past few years. Their knowledge inspired this project and their encouragement enabled me to carry it out. -

KANATA Vol. 3 Winter 2010

KANATA VOLUME 3 UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF THE INDIGENOUS STUDIES COMMUNITY OF MCGILL KANATA KANATA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF THE INDIGENOUS STUDIES COMMUNITY OF MCGILL VOLUME 3 WINTER 2010 McGILL UNIVERSITY MONTREAL, QUEBEC Acknowledgements Faculty, Administrative & Scholarly: Support and Advisors Kathryn Muller, Donna-Lee Smith, Michael Loft, Michael Doxtater, Like Moreau, Marianne Stenbaeck, Luke Moreau, Waneek Horn-Miller, Lynn Fletcher, Niigenwedom J. Sinclair, Karis Shearer, Keavy Martin, Lisa E. Stevenson, Morning Star, Rob Innes, Deanna Reder, Dean Jane Everett, Dean Christopher Manfredi, Jana Luker, Ronald Niezen Organisational Support McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC); First Peoples House (FPH); Borderless Worlds Volunteers (BWV); McGill University Joint Senate Board Subcommittee on First peoples’ Equity (JSBC-FPE); Anthropology Students Association(ASA); Student Society of McGill University (SSMU); Arts Undergraduate Society (AUS); Quebec Public Interest Research Group McGill (QPIRG) KANATA EXECUTIVE PRESIDENT, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PAMELA FILLION EXECUTIVE BOARD, EDITORIAL BOARD JAMES ROSS Paumalū CASSIDAY CHARLOTTE BURNS ALANNA BOCKUS SARA MARANDA-GAUVIN KRISTIN FILIATRAULT NICOLAS VAN BEEK SCOTT BAKER ROSALIE DION-PICARD CASSANDRA PORTER SOPHIA RASHID KAHN JOHN AYMES HOSSAI MAJID KEVIN WYLLIE DESIGN EDITORS JOHN AYMES PAUL COL For more information visit our website at: http://kanata.qpirgmcgill.org Submit content to KANATA, contact [email protected] Table of Contents Foreword- Editor’s Note 6 Pamela Fillion -

Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice by Jonathan A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OCAD University Open Research Repository Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice By Jonathan A. Lockyer A thesis presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts, 2014 Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University Toronto, Ontario Canada, April 2014 ©Jonathan A. Lockyer, April 2014 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature __________________________________________________ ii Abstract Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice Masters of Fine Arts, 2014 Jonathan A. Lockyer Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University This thesis establishes a critical genealogy of the history of curating Indigenous art in Canada from an Ontario-centric perspective. Since the pivotal intervention by Indigenous artists, curators, and political activists in the staging of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Quebec, the curation of Indigenous art in Canada has moved from a practice of necessity, largely unrecognized by mainstream arts institutions, to a professionalized practice that exists both within and on the margins of public galleries. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

Descarga Custodiada De Las Obras Hasta La Inauguración, En Lo Que Las Transformaciones Que El Turismo Provoca En Un País Que Está De Las Tierras Del Mundo

Madrinazgo de Honor / Honorary Patroness S.A.R. la Princesa de Asturias / H.R.H. the Princess of Asturias En un tiempo tan complejo y cambiante como el que vivimos, el documental se ha El festival también dedicará una retrospectiva a Hanns Eisler, uno de los convertido en un instrumento esencial para descubrir y analizar las múltiples aristas compositores más importantes de la Alemania de entreguerras. Con la llegada del y los insalvables obstáculos a los que nos enfrenta, con toda crudeza, una realidad nazismo dio el salto a Nueva York, donde puso música a películas de directores tan caprichosa e incierta. afamados como Joris Ivens, Joseph Losey, Alain Resnais. El director catalán Gonzalo Enterarse, estar al tanto, de cuanto sucede, cerca y lejos; sopesar necesidades Herralde y el realizador italiano Tommaso Cotronei recibirán especial atención en e inconvenientes; apoyar o rechazar desde logros espléndidos a abusos intolerables. Documenta Madrid 2010, además de Joseph Strick y Ben Russell, quienes sorprenderán 8 Todas estas acciones resumen la labor de un documentalista. Pero, al mismo tiempo, por su temática y modernidad. 9 estos también nos entretienen, nos hacen sonreír, o quizá llorar, con la belleza de También se abordará el trabajo del estadounidense Peter Hutton, deudor de historias ferozmente humanas. Porque el cine documental nos reta a observar la un documentalismo experimental, que filma en blanco y negro. Esta retrospectiva es realidad, imponiéndose como única meta la sinceridad del propio relato. Por ello, la más amplia dedicada a su obra en Europa. Por ello contaremos con la presencia del despierta adhesiones, siembra solidaridades y, en definitiva, ayuda a construir nuestro propio autor, que desgranará en una clase magistral las claves de su trabajo. -

ROSALIE FAVELL | Www

ROSALIE FAVELL www.rosaliefavell.com | www.wrappedinculture.ca EDUCATION PhD (ABD) Cultural Mediations, Institute for Comparative Studies in Art, Literature and Culture, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (2005 to 2009) Master of Fine Arts, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States (1998) Bachelor of Applied Arts in Photographic Arts, Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1984) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Rosalie Favell: Shifting Focus, Latcham Art Centre, Stoufville, Ontario, Canada. (October 20 – December 8) 2018 Facing the Camera, Station Art Centre, Whitby, Ontario, Canada. (June 2 – July 8) 2017 Wish You Were Here, Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, M’Chigeeng, Ontario, Canada. (May 25 – August 7) 2016 from an early age revisited (1994, 2016), Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Regina, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. (July – September) 2015 Rosalie Favell: (Re)Facing the Camera, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. (August 29 – November 22) 2014 Rosalie Favell: Relations, All My Relations, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. (December 12 – February 20, 2015) 2013 Muse as Memory: the Art of Rosalie Favell, Gallery of the College of Staten Island, New York City, New York, United States. (November 14 – December 19) 2013 Facing the Camera: Santa Fe Suite, Museum of Contemporary Native Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States. (May 25 – July 31) 2013 Rosalie Favell, Cube Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (April 2 – May 5) 2013 Wish You Were Here, Art Gallery of Algoma, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. (February 28 – May 26) 2012 Rosalie Favell Karsh Award Exhibition, Karsh Masson Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (September 7 – October 28) 2011 Rosalie Favell: Living Evidence, Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. -

Tutti Maria Lucia Martins

Dionne Brand and Alanis Obomsawin... 151 DIONNE BRAND AND ALANIS OBOMSAWIN: POLYPHONY IN THE POETICS OF RESISTANCE Maria Lúcia Milléo Martins Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Abstract Activist artists Dionne Brand and Alanis Obomsawin have much in common in their poetics of resistance. Brand’s writings and documentaries explore issues of displacement, race, gender, and colonialism, revealing a constant determination in giving voice to what was silenced or marginalized by the dominant culture. Similarly, Obomsawin’s documentaries show a long commitment to the history of aboriginal people, reclaiming their sovereignty of voice. Making use of polyphony, these two artists contest hegemonic discourses and a nationalist aesthetic that either ignores or appropriates difference. This study discusses the implications of polyphony in Brand’s poetry and two documentaries, Sisters in the Struggle and Long Time Comin’, and in Obomsawin’s documentaries, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance and Rocks at Whiskey Trench. All evidences demonstrate fine specimens of applied poetics, faithful to their ethics of resistance. KeywordsKeywords: Dionne Brand, Alanis Obomsawin, poetics of resistance, polyphony. Dionne Brand, Caribbean-Canadian writer and film-maker, and Alanis Obomsawin, Aboriginal-Canadian filmmaker and musician, Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 56 p. 151-164 jan./jun. 2009 152 Maria Lúcia Milléo Martins have a long repertoire in the poetics of resistance. Since the beginning of her career, Brand has been an activist in various fronts against discriminations of race, gender, and alien cultures of immigrants and aboriginals. She resists the myth of origin of Canada and all other forms of perpetuating colonialism and hegemony in the present.