Art, Artist, and Witness(Ing) in Canada's Truth and Reconciliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As of Aug 20, 2013

As of Aug 20, 2013 EXHIBIT SCHEDULE University of Alberta Telus Atrium Edmonton, AB October 2 – October 14, 2013 Organizers: Andrea Menard, Tanya Kappo, Tara Kappo First Nations University Gallery Regina, SK November 4 – December 20, 2013 Organizers: Judy Anderson & Katherine Boyer G’zaagin Art Gallery Parry Sound, ON Jan. 1 – 31, 2014 Organizing artist: Tracey Pawis Partners Hall/Town Hall Huntsville, ON Feb 10 – 14, 2014 Organizers: Teri Souter and Beth Ward Urban Shaman Gallery Winnipeg, MB March 7 – April 12, 2014 Organizing artists: Daina Warren & Marcel Balfour Aurora Cultural Centre Aurora, ON May 5 – June 26, 2014 Organizing artist: Nathalie Bertin c/o Christi Belcourt, P.O. Box 5191, Espanola, ON, P5E 1A0 / [email protected] / Facebook: Walking With Our Sisters 1 As of Aug 20, 2013 The NorVa Centre Flin Flon, MB July 14 to August 4, 2014 Contacts: Mike Spencer & Doreen Leigh Roman Metis Hall The Pas, MB August 11 – 18, 2014 Organizer: Suzanne Barbeau Bracegirdle Thunder Bay Art Gallery Thunder Bay, ON September 6 – October 18, 2014 Organizing Artist: Jean Marshall Saskatoon/Wanuskewin Saskatoon/Wanuskewin, SK November 1 - 30, 2014 Organizing Artist: Felicia Diedre Open Sky Creative Society Gallery Jan/Feb 2015 Fort Simpson, NT Organizer: Lynn Canney, Program Coordinator Yukon Arts Centre March 12 – May 15, 2015 Whitehorse, Yukon Organizing artist: Lena White The Jasper Habitat for the Arts Jasper National Park, Alberta June 26 - July 12, 2015 Organizer: Marianne Garrah Museum of Contemporary Native Arts Santa Fe, NM August 2015 Organizing Curator: Ryan Rice Gallery 101 Ottawa, ON September/October 2015 Organizing artists: Heather Wiggs & Laura Margita c/o Christi Belcourt, P.O. -

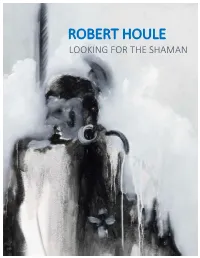

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

SETL for Internet Data Processing

SETL for Internet Data Processing by David Bacon A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Computer Science New York University January, 2000 Jacob T. Schwartz (Dissertation Advisor) c David Bacon, 1999 Permission to reproduce this work in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes is hereby granted, provided that this notice and the reference http://www.cs.nyu.edu/bacon/phd-thesis/ remain prominently attached to the copied text. Excerpts less than one PostScript page long may be quoted without the requirement to include this notice, but must attach a bibliographic citation that mentions the author’s name, the title and year of this disser- tation, and New York University. For my children ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Jack Schwartz, for his support and encour- agement. I am also grateful to Ed Schonberg and Robert Dewar for many interesting and helpful discussions, particularly during my early days at NYU. Terry Boult (of Lehigh University) and Richard Wallace have contributed materially to my later work on SETL through grants from the NSF and from ARPA. Finally, I am indebted to my parents, who gave me the strength and will to bring this labor of love to what I hope will be a propitious beginning. iii Preface Colin Broughton, a colleague in Edmonton, Canada, first made me aware of SETL in 1980, when he saw the heavy use I was making of associative tables in SPITBOL for data processing in a protein X-ray crystallography laboratory. -

Modern Programming Languages CS508 Virtual University of Pakistan

Modern Programming Languages (CS508) VU Modern Programming Languages CS508 Virtual University of Pakistan Leaders in Education Technology 1 © Copyright Virtual University of Pakistan Modern Programming Languages (CS508) VU TABLE of CONTENTS Course Objectives...........................................................................................................................4 Introduction and Historical Background (Lecture 1-8)..............................................................5 Language Evaluation Criterion.....................................................................................................6 Language Evaluation Criterion...................................................................................................15 An Introduction to SNOBOL (Lecture 9-12).............................................................................32 Ada Programming Language: An Introduction (Lecture 13-17).............................................45 LISP Programming Language: An Introduction (Lecture 18-21)...........................................63 PROLOG - Programming in Logic (Lecture 22-26) .................................................................77 Java Programming Language (Lecture 27-30)..........................................................................92 C# Programming Language (Lecture 31-34) ...........................................................................111 PHP – Personal Home Page PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor (Lecture 35-37)........................129 Modern Programming Languages-JavaScript -

Green Tech Exchange Forum

Green Tech Exchange Forum May 25, 2016 SFU Harbor Centre Presentation Chief Patrick Michell Kanaka Bar Indian Band “What we do to the lands, we do to ourselves.” The Indigenous People of Canada All diverse with distinct languages, culture and history. Canada • Celebrating 150 Years on July 1 2017 • 630 Bands • Metis and Inuit too British Columbia • Joined Canada in 1871 • 203 Bands The Nlaka’pamux Nation Archeology indicates an indigenous population living on the land for 7,000 years +. 1808: First Contact with French NWC with arrival of Simon Fraser. • First named Couteau Tribe. • Later renamed the Thompson Indian. 1857-58: Fought Americans to standstill in the Fraser Canyon War 1876: 69 villages amalgamated into 15 Indian Bands under the Indian Act 1878: Reserve Land allocations Kanaka Bar Indian Band • One of the original Nlaka’pamux communities. • Webpage: www.kanakabarband.ca • 66 members on reserve, 150 off • Codified: Election, Membership and Governance Codes in 2013. • Leadership: an indefinite term but face recall every 3rd Thursday. Land Use Plan (March 2015). Community Economic Development Plan (March 2016). Bi-annual implementation plans. Holistic: what one does affects another Kanaka Bar Indian Band Organization Chart As at May 2, 2016 Kanaka Bar & British Columbia Clean Energy Sectors Large Hydro Geothermal Tidal Wave N/A Applicable some day? N/A N/A Biomass Solar Run of River Wind Considered: not yet? 1.5 Projects 1.5 Projects Concept Stage How are we doing this? BC Hydro (the buyer of electrons) Self-sufficiency (off grid) Net Metering: projects under 100Kw Generating electrons for office, can connect to grid. -

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

L-G-0014502457-0046728341.Pdf

Keetsahnak / Our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Sisters KIM ANDERSON, MARIA CAMPBELL & CHRISTI BELCOURT, Editors Keetsahnak Our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Sisters 1 The University of Alberta Press Published by First edition, first printing, 2018. First electronic edition, 2018. The University of Alberta Press Copyediting and proofreading by Ring House 2 Joanne Muzak. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada t6g 2e1 Indexing by Judy Dunlop. www.uap.ualberta.ca Book design by Alan Brownoff. Copyright © 2018 The University of Cover image: Sherry Farrell Racette, She Alberta Press Grew Her Garden on Rough Ground, 2016, beadwork on moosehide. Used by permission library and archives canada cataloguing in publication All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored Keetsahnak / Our missing and in a retrieval system, or transmitted in murdered Indigenous sisters / any form or by any means (electronic, Kim Anderson, Maria Campbell & mechanical, photocopying, recording, Christi Belcourt, editors. or otherwise) without prior written consent. Contact the University of Alberta Includes bibliographical references Press for further details. and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. The University of Alberta Press supports isbn 978–1–77212–367–8 (softcover).— copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, isbn 978–1–77212–391–3 (epub).— encourages diverse voices, promotes free isbn 978–1–77212–392–0 (Kindle).— speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank isbn 978–1–77212–390–6 (pdf) you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with the copyright 1. Native women—Crimes against— laws by not reproducing, scanning, or Canada. 2. Native women—Crimes distributing any part of it in any form against—Canada—Prevention. -

Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese's Indian

Document generated on 09/29/2021 4:36 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse Jack Robinson Volume 38, Number 2, 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl38_2art05 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Robinson, J. (2013). Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 38(2), 88–105. All rights reserved, ©2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse Jack Robinson he Anishinaubae creation story, as related by Anishinaubae scholar Basil Johnston, tells that Kitchi- Manitou, the Great Mystery, made the earth from a vision, Tbut that all was devastated by a flood. Then a pregnant Manitou, Geezigho-quae, or Sky Woman, fell to this water world, and, from the back of a turtle, got the water animals to dive for Earth. From a small clump retrieved by Muskrat, using the power of thought or dream, she created Turtle Island, or North America. -

To Read an Excerpt from Claiming the Land

CONTENTS S List of Illustrations / ix Preface / xi INTRODUCTION Fraser River Fever on the Pacific Slope of North America / 1 CHAPTER 1 Prophetic Patterns: The Search for a New El Dorado / 13 CHAPTER 2 The Fur Trade World / 36 CHAPTER 3 The Californian World / 62 CHAPTER 4 The British World / 107 CHAPTER 5 Fortunes Foretold: The Fraser River War / 144 CHAPTER 6 Mapping the New El Dorado / 187 CHAPTER 7 Inventing Canada from West to East / 213 CONCLUSION “The River Bears South” / 238 Acknowledgements / 247 Appendices / 249 Notes / 267 Bibliography / 351 About the Author / 393 Index / 395 PREFACE S As a fifth-generation British Columbian, I have always been fascinated by the stories of my ancestors who chased “the golden butterfly” to California in 1849. Then in 1858 — with news of rich gold discoveries on the Fraser River — they scrambled to be among the first arrivals in British Columbia, the New El Dorado of the north. To our family this was “British California,” part of a natural north-south world found west of the Rocky Mountains, with Vancouver Island the Gibraltar-like fortress of the North Pacific. Today, the descendants of our gold rush ancestors can be found throughout this larger Pacific Slope region of which this history is such a part. My early curiosity was significantly moved by these family tales of adventure, my great-great-great Uncle William having acted as fore- man on many of the well-known roadways of the colonial period: the Dewdney and Big Bend gold rush trails, and the most arduous section of the Cariboo Wagon Road that traversed and tunnelled through the infamous Black Canyon (confronted by Simon Fraser just a little over 50 years earlier). -

Gail Gallagher

Art, Activism and the Creation of Awareness of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG); Walking With Our Sisters, REDress Project by Gail Gallagher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Native Studies University of Alberta © Gail Gallagher, 2020 ABSTRACT Artistic expression can be used as a tool to promote activism, to educate and to provide healing opportunities for the families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG). Indigenous activism has played a significant role in raising awareness of the MMIWG issue in Canada, through the uniting of various Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. The role that the Walking With Our Sisters (WWOS) initiative and the REDress project plays in bringing these communities together, to reduce the sexual exploitation and marginalization of Indigenous women, will be examined. These two commemorative projects bring an awareness of how Indigenous peoples interact with space in political and cultural ways, and which mainstream society erases. This thesis will demonstrate that through the process to bring people together, there has been education of the MMIWG issue, with more awareness developed with regards to other Indigenous issues within non-Indigenous communities. Furthermore, this paper will show that in communities which have united in their experience with grief and injustice, healing has begun for the Indigenous individuals, families and communities affected. Gallagher ii DEDICATION ka-kiskisiyahk iskwêwak êkwa iskwêsisak kâ-kî-wanihâyahkik. ᑲᑭᐢ ᑭᓯ ᔭ ᐠ ᐃᐢ ᑫᐧ ᐊᐧ ᕽ ᐁᑲᐧ ᐃᐢ ᑫᐧ ᓯ ᓴ ᐠ ᑳᑮᐊᐧ ᓂᐦ ᐋᔭᐦ ᑭᐠ We remember the women and girls we have lost.1 1 Cree Literacy Network. -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

Indian Horse

Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 Acknowledgements | Copyright For my wife, Debra Powell, for allowing me to bask in her light and become more. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. WENDELL BERRY, “The Peace of Wild Things” 1 My name is Saul Indian Horse. I am the son of Mary Mandamin and John Indian Horse. My grandfather was called Solomon so my name is the diminutive of his. My people are from the Fish Clan of the northern Ojibway, the Anishinabeg, we call ourselves. We made our home in the territories along the Winnipeg River, where the river opens wide before crossing into Manitoba after it leaves Lake of the Woods and the rugged spine of northern Ontario. They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses that thatch the edges of bays.