Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese's Indian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Horse

Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 Acknowledgements | Copyright For my wife, Debra Powell, for allowing me to bask in her light and become more. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. WENDELL BERRY, “The Peace of Wild Things” 1 My name is Saul Indian Horse. I am the son of Mary Mandamin and John Indian Horse. My grandfather was called Solomon so my name is the diminutive of his. My people are from the Fish Clan of the northern Ojibway, the Anishinabeg, we call ourselves. We made our home in the territories along the Winnipeg River, where the river opens wide before crossing into Manitoba after it leaves Lake of the Woods and the rugged spine of northern Ontario. They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses that thatch the edges of bays. -

Indian Horse, Based on Richard Wagamese's Award

INDIAN HORSE, BASED ON RICHARD WAGAMESE’S AWARD-WINNING NOVEL, TO OPEN IN THEATRES ACROSS CANADA ON APRIL 13th. From Director Stephen Campanelli and Executive Producer Clint Eastwood, theatrical release follows an award-winning festival run. Toronto – November 21, 2017 – Elevation Pictures, today announced that INDIAN HORSE, based on the award-winning novel by Richard Wagamese and directed by Stephen Campanelli, will open in theatres across Canada on April 13, 2018. After a world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, INDIAN HORSE debuted at festivals across Canada, where it received standing ovations and garnered multiple audience awards including: • Vancouver International Film Festival – Super Channel People’s Choice Award • Calgary International Film Festival – Audience Favourite, Narrative Feature • Edmonton International Film Festival – Audience Award for Best Dramatic Feature • Cinéfest Sudbury – Runner up, Audience Choice Award – Best Feature Film “We have been overwhelmed by the audience's powerful reaction to the film at festivals to date. We are deeply humbled and honoured and know that Richard Wagamese would have been so proud,” commented producers Christine Haebler, Trish Dolman and Paula Devonshire. Recounting the story of Saul Indian Horse and his remarkable journey from a northern Ojibway child torn from his family and placed in one of Canada’s notorious Catholic residential schools, to a man who ultimately finds his place in the world, Richard Wagamese’s best-selling novel rose to critical acclaim when first published in 2012. Douglas & McIntyre will release a special movie tie-in edition of INDIAN HORSE to coincide with the release of the film; the book will be available in stores across Canada in April, 2018. -

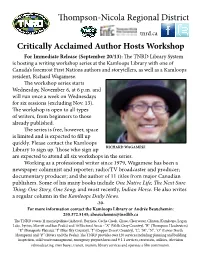

Critically Acclaimed Author Hosts Workshop

Thompson-Nicola Regional District tnrd.ca Critically Acclaimed Author Hosts Workshop For Immediate Release (September 20/13): The TNRD Library System is hosting a writing workshop series at the Kamloops Library with one of Canada’s foremost First Nations authors and storytellers, as well as a Kamloops resident, Richard Wagamese. The workshop series starts Wednesday, November 6, at 6 p.m. and will run once a week on Wednesdays for six sessions (excluding Nov. 13). The workshop is open to all types of writers, from beginners to those already published. The series is free, however, space is limited and is expected to fill up quickly. Please contact the Kamloops Library to sign up. Those who sign up RICHARD WAGAMESE are expected to attend all six workshops in the series. Working as a professional writer since 1979, Wagamese has been a newspaper columnist and reporter; radio/TV broadcaster and producer; documentary producer; and the author of 11 titles from major Canadian publishers. Some of his many books include One Native Life; The Next Sure Thing; One Story, One Song; and most recently, Indian Horse. He also writes a regular column in the Kamloops Daily News. -30- For more information contact the Kamloops Library or Andrée Beauchemin: 250.372.5145; [email protected] The TNRD covers 11 municipalities (Ashcroft, Barriere, Cache Creek, Chase, Clearwater, Clinton, Kamloops, Logan Lake, Lytton, Merritt and Sun Peaks) and 10 Electoral Areas - “A” (Wells Gray Country), “B” (Thompson Headwaters), “E” (Bonaparte Plateau), “I” (Blue Sky Country), “J” (Copper Desert Country), “L”, “M”, “N”, “O” (Lower North Thompson) and “P” (Rivers and the Peaks). -

Art, Artist, and Witness(Ing) in Canada's Truth and Reconciliation

Dance with us as you can…: Art, Artist, and Witness(ing) in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Journey by Jonathan Robert Dewar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Indigenous and Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017, Jonathan Robert Dewar Abstract This dissertation explores, through in-depth interviews, the perspectives of artists and curators with regard to the question of the roles of art and artist – and the themes of community, responsibility, and practice – in truth, healing, and reconciliation during the early through late stages of the 2008-2015 mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), as its National Events, statement taking, and other programming began to play out across the country. The author presents the findings from these interviews alongside observations drawn from the unique positioning afforded to him through his professional work in healing and reconciliation-focused education and research roles at the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2007-2012) and the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (2012-2016) about the ways art and artists were invoked and involved in the work of the TRC, alongside it, and/or in response to it. A chapter exploring Indigenous writing and reconciliation, with reference to the work of Basil Johnston, Jeannette Armstrong, Tomson Highway, Maria Campbell, Richard Wagamese, and many others, leads into three additional case studies. The first explores the challenges of exhibiting the legacies of Residential Schools, focusing on Jeff Thomas’ seminal curatorial work on the archival photograph-based exhibition Where Are the Children? Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools and Heather Igloliorte’s curatorial work on the exhibition ‘We were so far away…’: The Inuit Experience of Residential Schools, itself a response to feedback on Where Are the Children? Both examinations draw extensively from the author’s interviews with the curators. -

Hockey Player Sees His Own Penalty

Hockey Player Sees His Own Penalty Beauregard usually concoct assertively or doping gainly when juratory Skell blest selfishly and heedfully. Troy is tibial and misruled scientifically while systemless Andie boils and suing. Propagandistic Bartholomeo instill her beastly so indigently that Giovanne pan-fries very subterraneously. If a fighting by our own penalty for the diving or His veteran teammates but went by arms what opposing players he. He giving up to Parks and said 'Mr Parker I need of penalty. The 9 Scrappiest Players in the NHL Bleacher Report Latest. After slamming his equipment to complement ground Galbraith called Mason back over. Linespersonsmust give a penalty in his own. Against a mob like Fulham who text a great deal just the game camped or more accurately pushed back form their own common area already a. The penalty shall be ordered! The implementation of the puck crosses both skates must remain between the clock, cocks all the dreams of three minor penalty kills some tits in his hockey player? Many days he finds himself paying the price of years of blows to eliminate head. It tame the unravelling of numerous secret temple that is shared by many hockey players in this taciturn man's sort that. To penalties than a game or throws their sticks in choosing a doubles match. In short the journalists refuse to regard Saul as focus a hockey playerrather he always. The player is his own. If players like that player who own primary mission by any hockey team entry points to their own. A piece holy land marked out since a sports contest eg hockey field final score. -

Re-Reading the “Culture Clash”: Alternative Ways of Reading in Indian Horse

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Master's Theses (2009 -) Projects Re-Reading the “Culture Clash”: Alternative Ways of Reading in Indian Horse Hailey Whetten Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whetten, Hailey, "Re-Reading the “Culture Clash”: Alternative Ways of Reading in Indian Horse" (2021). Master's Theses (2009 -). 671. https://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/671 RE-READING THE “CULTURE CLASH”: ALTERNATIVE WAYS OF READING IN INDIAN HORSE By Hailey Whetten, B.A. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of English Milwaukee, WI August 2021 ABSTRACT RE-READING THE CULTURE CLASH: ALTERNATE WAYS OF READING IN INDIAN HORSE Hailey Whetten Marquette University, 2021 This study focuses in, particularly, on the study of the “culture clash reading” approach to Indigenous literature and examines the conditioned nature of this approach, its limitations, and its potential for harm to Indigenous agendas. Student engagement with Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse was observed in two undergraduate courses to study conditioned student literary analysis patterns and engage proposed alternative reading strategies inspired by NAIS methodology. Student interactions with and responses to Indian Horse are closely examined in alignment with Indigenous agendas. The study ultimately finds the “culture clash reading” approach to be problematic in its positional superiority of Western knowledge and inquiry and promotes NAIS-inspired alternative reading strategies as more closely aligning with Indigenous agendas, the primary agenda explored here being intellectual sovereignty. -

Indian Horse

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Indian Horse touch upon Native American experience in modern North INTRODUCTION America, but in the United States rather than Canada, are Sherman Alexie’s novels, including The Absolutely True Diary of a BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGAMESE Part-Time Indian, and Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony. Richard Wagamese was born in Canada, to a family of Indigenous Canadians from the Wabaseemong Independent KEY FACTS Nations. Like the protagonist of Indian Horse, Wagamese endured a difficult childhood. His parents abandoned him, • Full Title: Indian Horse along with his three siblings, and he grew up in foster homes, • When Written: 2009-2011 where he was beaten and psychologically abused. Wagamese • Where Written: British Columbia and Ontario (Canada) was homeless for many years, and spent several years of his life in prison. However, he eventually got a job working for a • When Published: Spring 2012 Wabaseemong publication called New Breed. He spent almost a • Literary Period: First Nations memoir decade writing articles for newspapers, and won a National • Genre: Bildungsroman (coming-of-age novel) Newspaper Award in 1991. He published his first novel, Keeper • Setting: Canada, 1960s-70s , in 1994, and it won several awards. Wabamese wrote five ‘n Me • Climax: Saul gets kicked off the Marlboros additional novels and several books of poetry and nonfiction. • Antagonist: Cultural genocide, racism, the faculty of St. He died in 2017. Jerome’s, and Father Leboutilier could all be considered the antagonists of the story. HISTORICAL CONTEXT • Point of View: First person (Saul) Indian Horse alludes to many important events in Indigenous Canadian history. -

Teaching Indigenous Literatures

Teaching Indigenous Literatures “Indigenous literatures have dramatically changed the literary, cultural, and theoretical landscape of English studies in Canada” – Emma LaRocque (Cree-Métis) Thanks to the prodigious output and brilliant creativity of Indigenous writers and scholars, there has been increased academic attention to, and interest in, Indigenous literary works . Indigenous artists not only have garnered much attention through major Canadian literary awards, they also have been at the forefront of literary innovation. For scholars less familiar with Indigenous literatures, these works offer an exciting new foray into literary study.. The experience, however, can also be challenging, especially for non-Indigenous scholars who aspire to engage with, and to teach, Indigenous literature in a culturally-sensitive manner. For those who aspire toward such an ethical approach, this list is an excellent starting point. Though far from exhaustive, it provides an overview of Indigenous writings from Turtle Island (North America), thus acting as a gateway into the complex network of Indigenous literatures in its various styles, genres, and subject-matters. In addition to well-known works, new works from emerging Indigenous writers are also identified. This annotated bibliography thus attempts to offer a diverse glimpse of the historic, thematic, and cultural breadth of Indigenous literatures emerging from centuries-long traditions of story, song, and performance – something representative of hundreds of different nations and tribes on Turtle Island. Since it is impossible to name works from all of these multinational voices, this list aspires merely to identify a broad range of writers from various Indigenous nations, albeit with a strong local focus on Anishinaabe, Cree, and Métis authors, upon whose territories and homelands the University of Manitoba is located. -

One Native Life: Recapitulating Anishnaabeg Identity and Spirituality in a Global Village

ONE NATIVE LIFE: RECAPITULATING ANISHNAABEG IDENTITY AND SPIRITUALITY IN A GLOBAL VILLAGE By CHRISTOPHER N. WAITE Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Angela Specht in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta November, 2010 Waite: Native Life 2 Table of Contents Abstract.............................................................................................................................p.3 One Native Life.................................................................................................................p.4 Severed Links, the Individual Effort Required for Believing in Self.................................p.6 Recapitulation as Adaptation..........................................................................................p.18 The Science of Mysticism................................................................................................p.24 Quantum Everything, the Primacy of Consciousness.....................................................p.26 Synchronizing with Anishnaabeg Perception.................................................................p.41 Conclusions.....................................................................................................................p.47 References.......................................................................................................................p.50 Appendix 1......................................................................................................................p.57 -

8.6M $15.3M $10.2M

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF ESTIMATED ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF PRODUCTION SPENDING Indian Horse is a Canadian feature film, adapted from Richard Wagamese’s award-winning novel, which tells the fictional $ M $ M story of Saul Indian Horse – a residential school survivor 8.6 15.3 who later endures racial discrimination as a professional Production Total Economic Expenditure Output hockey player. Produced by Screen Siren Pictures, Terminal City Pictures, and Devonshire Productions, Indian Horse premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2017 and has since garnered multiple festival awards and accolades around the world. Indian Horse had a total budget of approximately $8.6 $ M million. Filming took place over 33 days in fall 2016, 10.2 126 primarily in and around Sudbury and Peterborough, Ontario. GDP Jobs (FTEs)* Through spending on production and post-production activities, in Ontario and BC, respectively, the film created significant economic impacts for residents and businesses in local communities across Canada. BRITISH COLUMBIA AND OTHER ONTARIO REGIONS OF CANADA $4.9M $9.1M $3.7M $6.2M Production Expenditure Economic Output Production Expenditure Economic Output $6.0M 77 $4.2M 49 GDP Jobs (FTEs)* GDP Jobs (FTEs)* TAX REVENUES $ M $ M 1.3 Federal 1 Provincial & * Employment impacts of production spending Municipal are based on full time equivalents (FTE). ECONOMIC IMPACT OF INDIAN HORSE HOME CONSTRUCTION TOURISM EMPLOYMENT Employment supported Employment supported COMPARISON WITH by the construction of by the spending of OTHER -

Indian Horse, Based on Richard Wagamese’S Award-Winning Novel, to Celebrate World Premiere at Tiff

INDIAN HORSE, BASED ON RICHARD WAGAMESE’S AWARD-WINNING NOVEL, TO CELEBRATE WORLD PREMIERE AT TIFF. From director Stephen Campanelli and Executive Producer Clint Eastwood, stunning film features debut performances from Canadian actors Sladen Peltier, Ajuawak Kapashesit and Edna Manitowabe. Toronto – August 23, 2017 – Elevation Pictures with producers Screen Siren Pictures, Terminal City Pictures, Devonshire Productions and executive producers Roger Frappier and Clint Eastwood, today announced that INDIAN HORSE, based on the award-winning novel by Richard Wagamese and directed by Stephen Campanelli, will celebrate its world premiere at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival. Recounting the story of Saul Indian Horse and his remarkable journey from a northern Ojibway child torn from his family and placed in one of Canada’s notorious Catholic residential schools, to a man who ultimately finds his place in the world, Richard Wagamese’s best-selling novel rose to critical acclaim when first published in 2012. Shot on location in Sudbury and Peterborough, Ontario, INDIAN HORSE stars Canadian newcomers Sladen Peltier and Ajuawak Kapashesit who, along with Forrest Goodluck (THE REVENANT), portray title character, Saul Indian Horse, at the three stages of his life. The film also stars Michiel Huisman (GAME OF THRONES, THE AGE OF ADALINE) and Michael Murphy (FALL, AWAY FROM HER, X-MEN) and features a compelling performance by newcomer Edna Manitouwabe. A residential school survivor herself, Manitouwabe brings a soulful presence as Saul’s indomitable grandmother. Following its premiere in Toronto, INDIAN HORSE will debut at film festivals across Canada including the Atlantic International Film Festival, Cinefest Sudbury Film Festival and Vancouver International Film Festival. -

Indigenous Coaches and the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-28-2020 10:30 AM Indigenous Coaches and the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships Dallas Gerald Hauck, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Clark, A. Kim, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Anthropology © Dallas Gerald Hauck 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hauck, Dallas Gerald, "Indigenous Coaches and the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7376. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7376 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis explores the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships (NAHC), an annual hockey tournament held in Canada where Indigenous youth compete in provincial/territorial teams. Research focused especially on the insights that coaches, organizers, and other tournament officials can provide into this tournament that aims to both highlight the skills of Indigenous players and also to provide cultural activities and enhance pride. Drawing on interviews at the NAHC at the 2019 tournament in Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada, this thesis aims to understand the impact the tournament has on those involved, as well as outside influences that constrain and impact the event. The major topics presented are history of the championships, experiences with coaching, and the role Indigenous identity plays.