Indian Horse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes for Chapter Re-Drafts

Making Markets for Japanese Cinema: A Study of Distribution Practices for Japanese Films on DVD in the UK from 2008 to 2010 Jonathan Wroot PhD Thesis Submitted to the University of East Anglia For the qualification of PhD in Film Studies 2013 1 Making Markets for Japanese Cinema: A Study of Distribution Practices for Japanese Films on DVD in the UK from 2008 to 2010 2 Acknowledgements Thanks needed to be expressed to a number of people over the last three years – and I apologise if I forget anyone here. First of all, thank you to Rayna Denison and Keith Johnston for agreeing to oversee this research – which required reining in my enthusiasm as much as attempting to tease it out of me and turn it into coherent writing. Thanks to Mark Jancovich, who helped me get started with the PhD at UEA. A big thank you also to Andrew Kirkham and Adam Torel for doing what they do at 4Digital Asia, Third Window, and their other ventures – if they did not do it, this thesis would not exist. Also, a big thank you to my numerous other friends and family – whose support was invaluable, despite the distance between most of them and Norwich. And finally, the biggest thank you of all goes to Christina, for constantly being there with her support and encouragement. 3 Abstract The thesis will examine how DVD distribution can affect Japanese film dissemination in the UK. The media discourse concerning 4Digital Asia and Third Window proposes that this is the principal factor influencing their films’ presence in the UK from 2008 to 2010. -

Heart Leads Redvers to Sea the Stars Colt

WEDNESDAY, 23 OCTOBER 2019 SMULLEN: PROMOTION OF THE SPORT IS KEY HEART LEADS REDVERS TO By Pat Smullen SEA THE STARS COLT Oisin Murphy didn't end up with a big winner on Saturday but he's had a big year and that is the important thing. On Saturday I was thinking back to the work rate he has put in this year. He has ridden all over, travelling by plane, by helicopter, however he could get there to ride horses at two different meetings in a day, wherever they may be. His work ethic is something that needs to be applauded--that's what you need to do to be champion jockey. Oisin is not only an excellent rider but he is great for the game. He promotes our industry extremely well and I hope he does so for many years to come. I must admit, earlier in the year I was hoping that Danny Tudhope would be able to pull it off as the work that Danny has to put in to maintain his weight is phenomenal, and nobody sees that behind the scenes, but it wasn't to be. Cont. p5 Lot 98, who brought i400,000 Day 1 at the Arqana Oct Sale IN TDN AMERICA TODAY By Emma Berry SAFETY & WELFARE WITH BREEDERS’ CUP IN SIGHT DEAUVILLE, France-The seasons may change but the name at Dan Ross offers an in-depth look at the measures taken by Santa the top of the Arqana consignors' list does not. Ecurie des Anita in the run up to next month’s Breeders’ Cup. -

Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2012 Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Amy, "Threnody" (2012). English Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/21 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threnody By Amy Fitzgerald English Department Honors Project, May 2012 Advisor: Peter Bognanni 1 Glossary of Words, Terms, and Institutions Commissie voor Oorlogspleegkinderen : Commission for War Foster Children; formed after World War II to relocate war orphans in the Netherlands, most of whom were Jewish (Dutch) Crèche : nursery (French origin) Fraulein : Miss (German) Hervormde Kweekschool : Reformed (religion) teacher’s training college Hollandsche Shouwberg : Dutch Theater Huppah : Jewish wedding canopy Kaddish : multipurpose Jewish prayer with several versions, including the Mourners’ Kaddish KP (full name Knokploeg): Assault Group, a Dutch resistance organization LO (full name Landelijke Organasatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers): National Organization -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese's Indian

Document generated on 09/29/2021 4:36 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse Jack Robinson Volume 38, Number 2, 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl38_2art05 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Robinson, J. (2013). Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 38(2), 88–105. All rights reserved, ©2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse Jack Robinson he Anishinaubae creation story, as related by Anishinaubae scholar Basil Johnston, tells that Kitchi- Manitou, the Great Mystery, made the earth from a vision, Tbut that all was devastated by a flood. Then a pregnant Manitou, Geezigho-quae, or Sky Woman, fell to this water world, and, from the back of a turtle, got the water animals to dive for Earth. From a small clump retrieved by Muskrat, using the power of thought or dream, she created Turtle Island, or North America. -

The Thin Red Line

THE THIN RED LINE by Terrence Malick Based on the Novel by James Jones USE FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY To the Memory of James Jones And Those Who Served With Him They Live With Us It was an act of love. Those men on the line were my family, my home. They were closer to me than I can say, closer than my friends had been or ever would be. They had never let me down, and I could never do it to them. I had to be with them, rather than let them down and me live with the knowledge that I might have saved them. Men, I now know, do not fight for flag or country, for the Marine Corps or glory or any other abstraction. They fight for one another. Any man in combat who lacks comrades who will die for him, or for whom he is willing to die, is not a man at all. He is truly damned. William Manchester, the journalist, writing in Goodbye Darkness about his experience on Guadalcanal. (Like Fife, he walked away from the safety of a hospital in a secure area to return to his company in combat.) 2. COMPANY ROSTER (Partial) "C" CO, UMTH INF - Stein, James I, Capt, "C" Co Cmdg - Band, George R, 1st Lt, Exec - Whyte, William L, 2nd Lt, 1st P1 Cmdg - Blane, Thomas C, 2nd Lt, 2ns P1 Cmdg - Gore, Alberto O, 2nd Lt, 3rd P1 Cmdg - Culp, Robert (NMI), 2nd Lt, 4th (Weapons) P1 Cmdg EM 1st/Sgt - Welsh, Edward (NMI) S/Sgts - Grove, Ldr 1st P1 - Keck, Ldr 2nd P1 - MacTae, Supply - Stack, Ldr 3rd P1 - Storm, Mess Sgts - Becker, Sqd Ldr Rfl - Dranno, Co Clk - McCron, Sqd Ldr Rfl 3. -

Student Life, Government French Exchange

ROVING CAMERA U-HIGH Vol. 44, 1h 2 MIDWAY Partying, lounging, brunching: University high school, 1362 East 59th street, Chicago, Illinois 60637 Tuesday, October 8, 1968 great way to start the new year Student life, government impress• French exchange By DANIEL POLLOCK Editor-in-chief U-High's first American Field Service foreign. exchange student, Antoine Bertrand, 17, says a major difference between U-High and ms school anFrance is student govern ment and activities. "Life is more around school at U..Hi.gh,'' Antoine, . a senior, said. "In Flrance people just come to · : school for academic work. Here you CMe a lot more about aca r demic work and the main thing is that at U-High you have student government which has a say in certaiin things. and has certain Pholo bY Ken owrneo powers." NOTICE TO PARENTS feeling sorry for their poor children ANTOINE EXPLAINED that a laden with homework after six hours of intense study in school .student government was only just and summer hardly gone. It ain't all that bad. for example, be begun last year at his French fore the study gets too intense the whole school stops now for school, Lycee Internationale in St. l:m..mch (sweetrolls and milk) from Hl:40-10:55 a.m. from there Germain En Laye, west of Paris. it's only a short step to lunch at 12:45 p.m. The brunch has not noticeably cut down on an 's hmch intake. U-Highers really Antoine arrived in Chicago Sep enjoy food. Here Rand Wi waits for Carol Warshawsky to tember 1 and is staying at the hand over the brunch goodies. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film Announces Full Slate of NY Premieres

Media Contacts: Emma Myers, [email protected], 917-499-3339 Shannon Jowett, [email protected], 212-715-1205 Asako Sugiyama, [email protected], 212-715-1249 JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film Announces Full Slate of NY Premieres Dynamic 10th Edition Bursting with Nearly 30 Features, Over 20 Shorts, Special Sections, Industry Panel and Unprecedented Number of Special Guests July 14-24, 2016, at Japan Society "No other film showcase on Earth can compete with its culture-specific authority—or the quality of its titles." –Time Out New York “[A] cinematic cornucopia.” "Interest clearly lies with the idiosyncratic, the eccentric, the experimental and the weird, a taste that Japan rewards as richly as any country, even the United States." –The New York Times “JAPAN CUTS stands apart from film festivals that pander to contemporary trends, encouraging attendees to revisit the past through an eclectic slate of both new and repertory titles.” –The Village Voice New York, NY — JAPAN CUTS, North America’s largest festival of new Japanese film, returns for its 10th anniversary edition July 14-24, offering eleven days of impossible-to- see-anywhere-else screenings of the best new movies made in and around Japan, with special guest filmmakers and stars, post-screening Q&As, parties, giveaways and much more. This year’s expansive and eclectic slate of never before seen in NYC titles boasts 29 features (1 World Premiere, 1 International, 14 North American, 2 U.S., 6 New York, 1 NYC, and 1 Special Sneak Preview), 21 shorts (4 International Premieres, 9 North American, 1 U.S., 1 East Coast, 6 New York, plus a World Premiere of approximately 12 works produced in our Animation Film Workshop), and over 20 special guests—the most in the festival’s history. -

Indian Horse, Based on Richard Wagamese's Award

INDIAN HORSE, BASED ON RICHARD WAGAMESE’S AWARD-WINNING NOVEL, TO OPEN IN THEATRES ACROSS CANADA ON APRIL 13th. From Director Stephen Campanelli and Executive Producer Clint Eastwood, theatrical release follows an award-winning festival run. Toronto – November 21, 2017 – Elevation Pictures, today announced that INDIAN HORSE, based on the award-winning novel by Richard Wagamese and directed by Stephen Campanelli, will open in theatres across Canada on April 13, 2018. After a world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, INDIAN HORSE debuted at festivals across Canada, where it received standing ovations and garnered multiple audience awards including: • Vancouver International Film Festival – Super Channel People’s Choice Award • Calgary International Film Festival – Audience Favourite, Narrative Feature • Edmonton International Film Festival – Audience Award for Best Dramatic Feature • Cinéfest Sudbury – Runner up, Audience Choice Award – Best Feature Film “We have been overwhelmed by the audience's powerful reaction to the film at festivals to date. We are deeply humbled and honoured and know that Richard Wagamese would have been so proud,” commented producers Christine Haebler, Trish Dolman and Paula Devonshire. Recounting the story of Saul Indian Horse and his remarkable journey from a northern Ojibway child torn from his family and placed in one of Canada’s notorious Catholic residential schools, to a man who ultimately finds his place in the world, Richard Wagamese’s best-selling novel rose to critical acclaim when first published in 2012. Douglas & McIntyre will release a special movie tie-in edition of INDIAN HORSE to coincide with the release of the film; the book will be available in stores across Canada in April, 2018. -

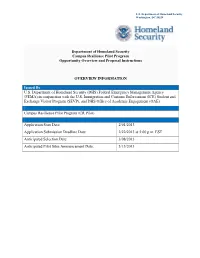

CR Pilot Program Announcement

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 Department of Homeland Security Campus Resilience Pilot Program Opportunity Overview and Proposal Instructions OVERVIEW INFORMATION Issued By U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in conjunction with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), and DHS Office of Academic Engagement (OAE). Opportunity Announcement Title Campus Resilience Pilot Program (CR Pilot) Key Dates and Time Application Start Date: 2/01/2013 Application Submission Deadline Date: 2/22/2013 at 5:00 p.m. EST Anticipated Selection Date: 3/08/2013 Anticipated Pilot Sites Announcement Date: 3/15/2013 DHS CAMPUS RESILIENCE PILOT PROGRAM PROPOSAL SUBMISSION PROCESS & ELIGIBILITY Opportunity Category Select the applicable opportunity category: Discretionary Mandatory Competitive Non-competitive Sole Source (Requires Awarding Office Pre-Approval and Explanation) CR Pilot sites will be selected based on evaluation criteria described in Section V. Proposal Submission Process Completed proposals should be emailed to [email protected] by 5:00 p.m. EST on Friday, February 22, 2013. Only electronic submissions will be accepted. Please reference “Campus Resilience Pilot Program” in the subject line. The file size limit is 5MB. Please submit in Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Word formats. An email acknowledgement of received submission will be sent upon receipt. Eligible Applicants The following entities are eligible to apply for participation in the CR Pilot: • Not-for-profit accredited public and state controlled institutions of higher education • Not-for-profit accredited private institutions of higher education Additional information should be provided under Full Announcement, Section III, Eligibility Criteria.