One Native Life: Recapitulating Anishnaabeg Identity and Spirituality in a Global Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese's Indian

Document generated on 09/29/2021 4:36 p.m. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse Jack Robinson Volume 38, Number 2, 2013 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/scl38_2art05 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 0380-6995 (print) 1718-7850 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Robinson, J. (2013). Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 38(2), 88–105. All rights reserved, ©2013 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Re-Storying the Colonial Landscape: Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse Jack Robinson he Anishinaubae creation story, as related by Anishinaubae scholar Basil Johnston, tells that Kitchi- Manitou, the Great Mystery, made the earth from a vision, Tbut that all was devastated by a flood. Then a pregnant Manitou, Geezigho-quae, or Sky Woman, fell to this water world, and, from the back of a turtle, got the water animals to dive for Earth. From a small clump retrieved by Muskrat, using the power of thought or dream, she created Turtle Island, or North America. -

Indian Horse

Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 Acknowledgements | Copyright For my wife, Debra Powell, for allowing me to bask in her light and become more. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. WENDELL BERRY, “The Peace of Wild Things” 1 My name is Saul Indian Horse. I am the son of Mary Mandamin and John Indian Horse. My grandfather was called Solomon so my name is the diminutive of his. My people are from the Fish Clan of the northern Ojibway, the Anishinabeg, we call ourselves. We made our home in the territories along the Winnipeg River, where the river opens wide before crossing into Manitoba after it leaves Lake of the Woods and the rugged spine of northern Ontario. They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses that thatch the edges of bays. -

Indian Horse, Based on Richard Wagamese's Award

INDIAN HORSE, BASED ON RICHARD WAGAMESE’S AWARD-WINNING NOVEL, TO OPEN IN THEATRES ACROSS CANADA ON APRIL 13th. From Director Stephen Campanelli and Executive Producer Clint Eastwood, theatrical release follows an award-winning festival run. Toronto – November 21, 2017 – Elevation Pictures, today announced that INDIAN HORSE, based on the award-winning novel by Richard Wagamese and directed by Stephen Campanelli, will open in theatres across Canada on April 13, 2018. After a world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, INDIAN HORSE debuted at festivals across Canada, where it received standing ovations and garnered multiple audience awards including: • Vancouver International Film Festival – Super Channel People’s Choice Award • Calgary International Film Festival – Audience Favourite, Narrative Feature • Edmonton International Film Festival – Audience Award for Best Dramatic Feature • Cinéfest Sudbury – Runner up, Audience Choice Award – Best Feature Film “We have been overwhelmed by the audience's powerful reaction to the film at festivals to date. We are deeply humbled and honoured and know that Richard Wagamese would have been so proud,” commented producers Christine Haebler, Trish Dolman and Paula Devonshire. Recounting the story of Saul Indian Horse and his remarkable journey from a northern Ojibway child torn from his family and placed in one of Canada’s notorious Catholic residential schools, to a man who ultimately finds his place in the world, Richard Wagamese’s best-selling novel rose to critical acclaim when first published in 2012. Douglas & McIntyre will release a special movie tie-in edition of INDIAN HORSE to coincide with the release of the film; the book will be available in stores across Canada in April, 2018. -

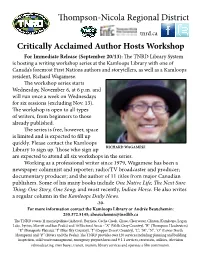

Critically Acclaimed Author Hosts Workshop

Thompson-Nicola Regional District tnrd.ca Critically Acclaimed Author Hosts Workshop For Immediate Release (September 20/13): The TNRD Library System is hosting a writing workshop series at the Kamloops Library with one of Canada’s foremost First Nations authors and storytellers, as well as a Kamloops resident, Richard Wagamese. The workshop series starts Wednesday, November 6, at 6 p.m. and will run once a week on Wednesdays for six sessions (excluding Nov. 13). The workshop is open to all types of writers, from beginners to those already published. The series is free, however, space is limited and is expected to fill up quickly. Please contact the Kamloops Library to sign up. Those who sign up RICHARD WAGAMESE are expected to attend all six workshops in the series. Working as a professional writer since 1979, Wagamese has been a newspaper columnist and reporter; radio/TV broadcaster and producer; documentary producer; and the author of 11 titles from major Canadian publishers. Some of his many books include One Native Life; The Next Sure Thing; One Story, One Song; and most recently, Indian Horse. He also writes a regular column in the Kamloops Daily News. -30- For more information contact the Kamloops Library or Andrée Beauchemin: 250.372.5145; [email protected] The TNRD covers 11 municipalities (Ashcroft, Barriere, Cache Creek, Chase, Clearwater, Clinton, Kamloops, Logan Lake, Lytton, Merritt and Sun Peaks) and 10 Electoral Areas - “A” (Wells Gray Country), “B” (Thompson Headwaters), “E” (Bonaparte Plateau), “I” (Blue Sky Country), “J” (Copper Desert Country), “L”, “M”, “N”, “O” (Lower North Thompson) and “P” (Rivers and the Peaks). -

Indian Horse, Based on Richard Wagamese’S Award-Winning Novel, to Celebrate World Premiere at Tiff

INDIAN HORSE, BASED ON RICHARD WAGAMESE’S AWARD-WINNING NOVEL, TO CELEBRATE WORLD PREMIERE AT TIFF. From director Stephen Campanelli and Executive Producer Clint Eastwood, stunning film features debut performances from Canadian actors Sladen Peltier, Ajuawak Kapashesit and Edna Manitowabe. Toronto – August 23, 2017 – Elevation Pictures with producers Screen Siren Pictures, Terminal City Pictures, Devonshire Productions and executive producers Roger Frappier and Clint Eastwood, today announced that INDIAN HORSE, based on the award-winning novel by Richard Wagamese and directed by Stephen Campanelli, will celebrate its world premiere at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival. Recounting the story of Saul Indian Horse and his remarkable journey from a northern Ojibway child torn from his family and placed in one of Canada’s notorious Catholic residential schools, to a man who ultimately finds his place in the world, Richard Wagamese’s best-selling novel rose to critical acclaim when first published in 2012. Shot on location in Sudbury and Peterborough, Ontario, INDIAN HORSE stars Canadian newcomers Sladen Peltier and Ajuawak Kapashesit who, along with Forrest Goodluck (THE REVENANT), portray title character, Saul Indian Horse, at the three stages of his life. The film also stars Michiel Huisman (GAME OF THRONES, THE AGE OF ADALINE) and Michael Murphy (FALL, AWAY FROM HER, X-MEN) and features a compelling performance by newcomer Edna Manitouwabe. A residential school survivor herself, Manitouwabe brings a soulful presence as Saul’s indomitable grandmother. Following its premiere in Toronto, INDIAN HORSE will debut at film festivals across Canada including the Atlantic International Film Festival, Cinefest Sudbury Film Festival and Vancouver International Film Festival. -

Indigenous Coaches and the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-28-2020 10:30 AM Indigenous Coaches and the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships Dallas Gerald Hauck, The University of Western Ontario Supervisor: Clark, A. Kim, The University of Western Ontario A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the Master of Arts degree in Anthropology © Dallas Gerald Hauck 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hauck, Dallas Gerald, "Indigenous Coaches and the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships" (2020). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 7376. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7376 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis explores the National Aboriginal Hockey Championships (NAHC), an annual hockey tournament held in Canada where Indigenous youth compete in provincial/territorial teams. Research focused especially on the insights that coaches, organizers, and other tournament officials can provide into this tournament that aims to both highlight the skills of Indigenous players and also to provide cultural activities and enhance pride. Drawing on interviews at the NAHC at the 2019 tournament in Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada, this thesis aims to understand the impact the tournament has on those involved, as well as outside influences that constrain and impact the event. The major topics presented are history of the championships, experiences with coaching, and the role Indigenous identity plays. -

Place-Based Identity in Northwestern Ontario Anishinaabe Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive PLACE-BASED IDENTITY IN NORTHWESTERN ONTARIO ANISHINAABE LITERATURE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By ADAR CHARLTON © Copyright Adar Charlton, December, 2018. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada i ABSTRACT Place-based identity for Indigenous peoples in the land currently known as Canada, although foundational to many Indigenous land ethics, has been fraught by colonial processes of displacement, reserve designation, and racism. -

Winter 2021 | January to March Reetings from the Past, in the Early Summer of 2020 When This Catalogue Went to Press

orcaorca bookbook publisherspublishers winter 2021 | January to March reetings from the past, in the early summer of 2020 when this catalogue went to press. GFrom this vantage point we have seen cautious reopening of the economy and are starting to see books leaving the warehouse and making their way to stores. We have been breathing a tentative sigh of relief as things appear to be returning to some sense of “normal.” We believe deeply in the work we do and the work you do. And we know that what we collectively do has never been more important. Let’s get through this together…stay safe, stay positive and look out for those more vulnerable and less fortunate. Andrew Wooldridge | Publisher 9781459823204 BB • $10.95 9781459823167 BB • $10.95 9781459818644 BB • $10.95 Quill & Quire “Beguiling.” Publishers Weekly Kirkus Reviews —Publishers Weekly 9781459827530 HC • $19.95 9781459824492 HC • $19.95 9781459818552 HC • $19.95 “Perfect.” “Colorful and comical.” “Told with empathy.” —Them. —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews 9781459821279 HC • $19.95 9781459823525 HC • $19.95 9781459819054 HC • $19.95 “Captivating.” “A sweet harangue.” “Gorgeous.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Booklist 9781459823617 PB • $7.95 9781459825567 PB • $12.95 9781459827875 PB • $10.95 9781459824874 PB • $14.95 Kirkus Reviews School Library Journal “Reassures and provides hope.” “A touching, heartfelt story.” —CanLit for Little Canadians —Kirkus Reviews 9781459824393 PB • $14.95 9781459824362 PB • $9.95 9781459826359 PB • $10.95 9781459818866 PB • $24.95 “Bold, subversive, -

How Indigenous Storytelling Shapes Residential School Testimony

Restorying Relationships and Performing Resurgence: How Indigenous Storytelling Shapes Residential School Testimony by Melanie Braith A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Theatre, Film, and Media University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2020 by Melanie Braith i Abstract This dissertation argues that an understanding of Indigenous storytelling can change how audiences engage with residential school survivors’ testimonies. From 2009 to 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) recorded residential school survivors’ stories. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation published these recordings online to meet survivors’ desire for their stories to be a learning opportunity. Any audience’s learning process is, however, contingent on their understanding of testimony. The most prominent Western understandings of testimony come from the contexts of courtroom testimony and trauma theory. Their theoretical underpinnings, however, emerge from epistemologies that are often incommensurable with Indigenous epistemologies, which can lead to a misreading of residential school testimonies. Looking at residential school testimonies through the lens of Indigenous oral storytelling, an inherently relational practice that creates and takes care of relationships, is an ethical alternative that allows audiences to recognize how these testimonies are a future-oriented process and restore relationships and responsibilities. My main argument is that Indigenous literatures can teach us how to apply the principles of Indigenous storytelling to residential school testimony. Indigenous epistemologies understand theory as a way of explaining processes by enacting those processes. Based on this, I argue that residential school novels reflect on the process of telling residential school stories by way of telling them. -

Richard Wagamese's Indian Horse: Stolen Memories and Recovered Histories Memoria Robada E Historias Recobradas En Indian Hors

Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse: Stolen Memories and Recovered Histories Franck Miroux ACTIO NOVA: REVISTA DE TEORÍA DE LA LITERATURA Y LITERATURA COMPARADA, nº 3, pp.194-230 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15366/actionova2019.3.009 RICHARD WAGAMESE’S INDIAN HORSE: STOLEN MEMORIES AND RECOVERED HISTORIES MEMORIA ROBADA E HISTORIAS RECOBRADAS EN INDIAN HORSE DE RICHARD WAGAMESE Franck Miroux Université Toulouse Jean-Jaurès ABSTRACT This paper purports to explore the narrative devices which enable the Anishinaabe Canadian author Richard Wagamese to compel the reader of his novel Indian Horse (2012) to experience the same violence as that faced by the young protagonist when the repressed memory of the terrible abuse suffered at an Indian residential school resurfaces decades after, disrupting the apparently linear course of the story. This study also seeks to show that Wagamese offers a major contribution to the rewriting of the history of residential schools in Canada by reclaiming Aboriginal narrative forms as a means to recover stolen memories, and thus to reconstruct both the fragmented (his)story and the shattered self. Keywords: Wagamese (Richard), residential schools, memory, history (rewriting), Aboriginal literatures (Canada). ACTIO NOVA: REVISTA DE TEORÍA DE LA LITERATURA Y LITERATURA COMPARADA. ISSN 2530-4437 https://revistas.uam.es/actionova 194 Richard Wagamese’s Indian Horse: Stolen Memories and Recovered Histories Franck Miroux ACTIO NOVA: REVISTA DE TEORÍA DE LA LITERATURA Y LITERATURA COMPARADA, nº 3, pp.194-230 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15366/actionova2019.3.009 RESUMEN Este artículo pone de manifiesto las estrategias narrativas mediante las cuales el autor anishinaabe canadiense Richard Wagamese somete al lector de su novela Indian Horse (2012) a la misma violencia sufrida por el joven héroe cuando la repentina resurgencia del recuerdo traumático reprimido acaba rompiendo la linealidad aparente de su historia. -

A Country Built on Promises Why Everyone Suffers When Canada Ignores Treaties with Aboriginals

selling sex M& grow-op panic Yesterday’sORAL vices, Occupy the internet! PAGE 6 MATTERS : $6.50 Vol. 22, No. 6 July/August 2014 Terry Fenge and Tony Penikett A country built on promises Why everyone suffers when Canada ignores treaties with aboriginals ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Suanne Kelman Tom Flanagan’s ironic downfall Nick Mount McLuhan and Frye: Together at last? Sarah Jennings Great War graveyards PLUS: NON-FICTION Philippe Lagassé on military–civilian tensions + Madeleine Thien on Esi Edugyan’s global wanderings + James Roots on the cottage romance + Rankin Sherling on the value of religious impurity FICTION Publications Mail Agreement #40032362 Katherine Ashenburg reviews The Rise and Fall of Great Powers by Tom Rachman + Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. Susan Walker reviews Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese PO Box 8, Station K Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 POETRY Deanna Young + Seymour Mayne + Kayla Czaga New from University of Toronto Press Dynamic Fair Dealing Governing Urban Economies Commissions of Inquiry and Creating Canadian Culture Online Innovation and Inclusion in Canadian City Policy Change Regions edited by Rosemary J. Coombe, Darren A Comparative Analysis Wershler, and Martin Zeilinger edited by Neil Bradford and Allison Bramwell edited by Gregory J. Inwood and Dynamic Fair Dealing explores the extent Governing Urban Economies examines Carolyn M. Johns to which copyright has expanded into the relations between governments and What role do commissions play in policy every facet of society and how our communities in Canadian city-regions and change? Why do some commissions result capacity to deal fairly with cultural goods breaks new ground tracking the ways in in policy changes while others do not? has suffered in the process. -

Decolonizing Autoethnography: Where's

DECOLONIZING AUTOETHNOGRAPHY: WHERE’S THE WATER IN KINESIOLOGY? by Stephanie Marianne Woodworth A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Stephanie Marianne Woodworth 2018 ii Decolonizing autoethnography: Where’s the water in kinesiology? Stephanie Marianne Woodworth Master of Science Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Kinesiology is a multi-disciplinary field studying the human body in relation to movement, and, yet, water is largely taken-for-granted. This is astonishing, considering ~70% of the human body is comprised of water and access to (reliable, safe, clean) water fundamentally shapes human lives. Furthermore, identities, geographies, histories, societies, cultures, economics, and politics have been, and continue to be, shaped by water. Therefore, to enhance decolonial water education in kinesiology, this thesis is presented in three “braided streams”. First, I critically reflect on my settler colonial history and complicity in relation to water issues impacting First Nations. Next, I critique kinesiology’s research, teaching, and practices to establish “where’s the water in kinesiology?” Last, with consent and support from Grandmother Josephine Mandamin and Joanne Robertson, I am contributing to an archive and story map of the Mother Earth Water Walks (2003-2018), an Anishinabe ceremony that nourishes sacred relationships between peoples and waters. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As humans, we are continuously shaped, molded and (re)created by our relationships. We are a creation of the entanglement of our relations. And, so, we must acknowledge and give thanks to all our relations. Richard Wagamese (Anishinabe) (Wabaseemoong Independent Nations) (2016) writes: “I’ve been considering the phrase “all my relations” for some time now.