Farrell & Waatainen, 2020 Canadian Social Studies, Volume 51

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

Green Tech Exchange Forum

Green Tech Exchange Forum May 25, 2016 SFU Harbor Centre Presentation Chief Patrick Michell Kanaka Bar Indian Band “What we do to the lands, we do to ourselves.” The Indigenous People of Canada All diverse with distinct languages, culture and history. Canada • Celebrating 150 Years on July 1 2017 • 630 Bands • Metis and Inuit too British Columbia • Joined Canada in 1871 • 203 Bands The Nlaka’pamux Nation Archeology indicates an indigenous population living on the land for 7,000 years +. 1808: First Contact with French NWC with arrival of Simon Fraser. • First named Couteau Tribe. • Later renamed the Thompson Indian. 1857-58: Fought Americans to standstill in the Fraser Canyon War 1876: 69 villages amalgamated into 15 Indian Bands under the Indian Act 1878: Reserve Land allocations Kanaka Bar Indian Band • One of the original Nlaka’pamux communities. • Webpage: www.kanakabarband.ca • 66 members on reserve, 150 off • Codified: Election, Membership and Governance Codes in 2013. • Leadership: an indefinite term but face recall every 3rd Thursday. Land Use Plan (March 2015). Community Economic Development Plan (March 2016). Bi-annual implementation plans. Holistic: what one does affects another Kanaka Bar Indian Band Organization Chart As at May 2, 2016 Kanaka Bar & British Columbia Clean Energy Sectors Large Hydro Geothermal Tidal Wave N/A Applicable some day? N/A N/A Biomass Solar Run of River Wind Considered: not yet? 1.5 Projects 1.5 Projects Concept Stage How are we doing this? BC Hydro (the buyer of electrons) Self-sufficiency (off grid) Net Metering: projects under 100Kw Generating electrons for office, can connect to grid. -

To Read an Excerpt from Claiming the Land

CONTENTS S List of Illustrations / ix Preface / xi INTRODUCTION Fraser River Fever on the Pacific Slope of North America / 1 CHAPTER 1 Prophetic Patterns: The Search for a New El Dorado / 13 CHAPTER 2 The Fur Trade World / 36 CHAPTER 3 The Californian World / 62 CHAPTER 4 The British World / 107 CHAPTER 5 Fortunes Foretold: The Fraser River War / 144 CHAPTER 6 Mapping the New El Dorado / 187 CHAPTER 7 Inventing Canada from West to East / 213 CONCLUSION “The River Bears South” / 238 Acknowledgements / 247 Appendices / 249 Notes / 267 Bibliography / 351 About the Author / 393 Index / 395 PREFACE S As a fifth-generation British Columbian, I have always been fascinated by the stories of my ancestors who chased “the golden butterfly” to California in 1849. Then in 1858 — with news of rich gold discoveries on the Fraser River — they scrambled to be among the first arrivals in British Columbia, the New El Dorado of the north. To our family this was “British California,” part of a natural north-south world found west of the Rocky Mountains, with Vancouver Island the Gibraltar-like fortress of the North Pacific. Today, the descendants of our gold rush ancestors can be found throughout this larger Pacific Slope region of which this history is such a part. My early curiosity was significantly moved by these family tales of adventure, my great-great-great Uncle William having acted as fore- man on many of the well-known roadways of the colonial period: the Dewdney and Big Bend gold rush trails, and the most arduous section of the Cariboo Wagon Road that traversed and tunnelled through the infamous Black Canyon (confronted by Simon Fraser just a little over 50 years earlier). -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

MANAGING DISCORD in the AMERICAS Great Britain and the United States 1886-1896

MANAGING DISCORD IN THE AMERICAS Great Britain and the United States 1886-1896 GERER LA DISCORDE DANS LES AMERIQUES La Grande-Bretagne et les Etats-Unis 1886-1896 A Thesis Submitted To the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada By Charles Robertson Maier, CD, MA In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2010 ©This Thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69195-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69195-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Drawing of Colonial Victoria “Victoria, on Vancouver Island.” Artist: Linton (Ca. 1857). (BC Archives, Call No. G-03249)

��� ����������������������������� � � � ������������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������� ������������������������������������ � � � � ��� ������������������������ � �������������������������������������������������������������� � � ���������������������� ������������������ � �������������� ������������� ��������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������� ����������������� ����������� � ��������������������������������� � ��������� ����������� ���������������������� ����������������������� �� ����������� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � ��� ������������������������������ � ����������� ���������������������� ����������������������� ����������� ��������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������ ���������� ������ ������������������������� ��������������� ������������������������ ������������ ��������� ����������������������������� �������������������������� �������� ������������������������������ ������������������������������� �������������������������������� ������������ ���������� ���������������������������� ������������������������������ ������������������������������� ��������������������������������� ���������������������� ���������������������������� ������������ ���������������������� ���������������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������������� ��������������� ������������������������������ ����������������������������� ����������� �������������������������� ������������������������ -

The Global Irish and Chinese: Migration, Exclusion, and Foreign Relations Among Empires, 1784-1904

THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Washington, DC April 6, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Barry Patrick McCarron All Rights Reserved ii THE GLOBAL IRISH AND CHINESE: MIGRATION, EXCLUSION, AND FOREIGN RELATIONS AMONG EMPIRES, 1784-1904 Barry Patrick McCarron, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Carol A. Benedict, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation is the first study to examine the Irish and Chinese interethnic and interracial dynamic in the United States and the British Empire in Australia and Canada during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Utilizing comparative and transnational perspectives and drawing on multinational and multilingual archival research including Chinese language sources, “The Global Irish and Chinese” argues that Irish immigrants were at the forefront of anti-Chinese movements in Australia, Canada, and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. Their rhetoric and actions gave rise to Chinese immigration restriction legislation and caused major friction in the Qing Empire’s foreign relations with the United States and the British Empire. Moreover, Irish immigrants east and west of the Rocky Mountains and on both sides of the Canada-United States border were central to the formation of a transnational white working-class alliance aimed at restricting the flow of Chinese labor into North America. Looking at the intersections of race, class, ethnicity, and gender, this project reveals a complicated history of relations between the Irish and Chinese in Australia, Canada, and the United States, which began in earnest with the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes in California, New South Wales, Victoria, and British Columbia. -

Environmental Histories of the Confederation Era Workshop, Charlottetown, PEI, 31 July – 1Aug

The Dominion of Nature: Environmental Histories of the Confederation Era workshop, Charlottetown, PEI, 31 July – 1Aug Draft essays. Do not cite or quote without permission. Wendy Cameron (Independent researcher), “Nature Ignored: Promoting Agricultural Settlement in the Ottawa Huron Tract of Canada West / Ontario” William Knight (Canada Science & Tech Museum), “Administering Fish” Andrew Smith (Liverpool), “A Bloomington School Perspective on the Dominion Fisheries Act of 1868” Brian J Payne (Bridgewater State), “The Best Fishing Station: Prince Edward Island and the Gulf of St. Lawrence Mackerel Fishery in the Era of Reciprocal Trade and Confederation Politics, 1854-1873” Dawn Hoogeveen (UBC), “Gold, Nature, and Confederation: Mining Laws in British Columbia in the wake of 1858” Darcy Ingram (Ottawa), “No Country for Animals? National Aspirations and Governance Networks in Canada’s Animal Welfare Movement” Randy Boswell (Carleton), “The ‘Sawdust Question’ and the River Doctor: Battling pollution and cholera in Canada’s new capital on the cusp of Confederation” Joshua MacFadyen (Western), “A Cold Confederation: Urban Energy Linkages in Canada” Elizabeth Anne Cavaliere (Concordia), “Viewing Canada: The cultural implications of topographic photographs in Confederation era Canada” Gabrielle Zezulka (Independent researcher), “Confederating Alberta’s Resources: Survey, Catalogue, Control” JI Little (Simon Fraser), “Picturing a National Landscape: Images of Nature in Picturesque Canada” 1 NATURE IGNORED: PROMOTING AGRICULTURAL SETTLEMENT IN -

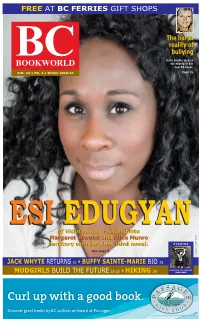

Esi Edugyan's

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

Chinese Settlement in Canada

1 Chinese Settlement in Canada 1788-89: The first recorded Asians to arrive in Canada were from Macau and Guangdong province in Southern China. They were sailors, smiths, and carpenters brought to Vancouver Island by the British Captain John Meares to work as shipwrights. Meares transported 50 Chinese workers in 1788 and 70 more in 1789, but shortly thereafter his entire Chinese crew was captured and imprisoned when the Spanish seized Nootka Sound. What happened to them is a mystery. There are reports John Meares, the British captain who that some were taken as forced labourers to Mexico, that brought the first known Chinese to some escaped, and that some were captured by the Canada Nootka people and married into their community. The Fraser Canyon Gold Rush In 1856, gold was found near the Fraser River in the territory of the Nlaka’pamux First Nations people. Almost immediately, the discovery brought tens of thousands of gold miners to the region, many of them prospectors from California. This event marked the beginnings of white settlement on British Columbia’s mainland. Chinese man washing gold in the Fraser River (1875) Credit: Library and Archives Canada / PA-125990 By 1858, Chinese gold miners had also started to arrive. Initially they too came from San Francisco, but ships carrying Chinese from Hong Kong soon followed. By the 1860s, there were 6000-7000 Chinese people living in B.C. The Gold Rush brought not only Chinese miners to Western Canada, but also the merchants, labourers, domestics, gardeners, cooks, launderers, and other service industry workers needed to support the large mining communities that sprang up wherever gold was discovered. -

1 SCT File No.: SPECIFIC CLAIMS TRIBUNAL BETWEEN: KANAKA

SCT File No.: SPECIFIC CLAIMS TRIBUNAL BETWEEN: KANAKA BAR INDIAN BAND Claimant v. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN THE RIGHT OF CANADA As represented by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Respondent DECLARATION OF CLAIM Pursuant to Rule 41 of the Specific Claims Tribunal Rules of Practice and Procedure This Declaration of Claim is filed under the provision of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act and the Specific Claims Tribunal Rules of Practice and Procedure. October 19, 2018 _________________________ (Registry Officer) TO: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN THE RIGHT OF CANADA Assistant Deputy Attorney General, Litigation, Justice Canada Bank of Canada Building 234 Wellington Street East Tower Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H8 Fax number: (613) 954-1920 1 I. Claimant 1. The Claimant, Kanaka Bar Indian Band (the “Band”) confirms that it is a First Nation within the meaning of s. 2 of the Specific Claim Tribunal Act (the “Act”) by being a “band” within the meaning of the Indian Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-5, as amended in the Province of British Columbia. II. Conditions Precedent (R. 41(c)) 2. The following conditions precedent as set out in s. 16(1) of the Act, have been fulfilled: 16. (1) A First Nation may file a claim with the Tribunal only if the claim has been previously filed with the Minster and (a) the Minister has notified the First Nation in writing of his or her decision not to negotiate the claim, in whole or in part; 3. On or about May 4, 2011, the Band filed a specific claim in respect to the illegal pre-emption in 1861 and subsequent alienation of a portion of the Band’s settlement at T’aqt’agtn (the “Claim”), now designated Lot 4, G.1, Kamloops Division of Yale Land District (“Lot 4”) with the Specific Claims Branch of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada. -

The Sto:Lo's Stolen Children by Andrew Seal the Fraser River Winds Through the Valley. the Lush, Forest-Covered Mountains T

The Sto:lo’s Stolen Children By Andrew Seal The Fraser River winds through the valley. The lush, forest-covered mountains tower in the background. This is what some Sto:lo boys saw the last time they were at home with their families. The view from Telte Yet campsite where the memorial will stand (Andrew Seal). In 1858, the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush brought the first influx of non-Indigenous people, or Xwelitem, to the area around Fort Hope, now known as Hope, B.C. When the rush was over, most of the miners returned to the United States with their bounty. However, at least a few of them took something far more precious than gold back home with them. No one knows just how many Sto:lo boys were taken. Some were abandoned further downstream, but most of them ended up in California. The view from what is now Telte Yet campsite on the banks of the Fraser would be their last sight of Hope. On August 19, a memorial pole, currently being carved by Chief Terry Horne of Yakweakwioose First Nation, will be erected there in their honour. Chief Terry Horne working on the memorial pole on the side of the Fraser River (Diana Bonner Cornell/Bear Image Productions) “It’s where [some of] the boys last touched Sto:lo territory,” says Chief Horne. The story is not well known even among the Sto:lo community, but details are surfacing now thanks to the efforts of Dr. Keith Carlson, a history professor at the University of Saskatchewan. His on-going research is part of the Canada 150-funded ‘Lost Stories’ initiative based at Concordia University, and should be featured as part of a larger work on the history of abducted Coast Salish children.