The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

Green Tech Exchange Forum

Green Tech Exchange Forum May 25, 2016 SFU Harbor Centre Presentation Chief Patrick Michell Kanaka Bar Indian Band “What we do to the lands, we do to ourselves.” The Indigenous People of Canada All diverse with distinct languages, culture and history. Canada • Celebrating 150 Years on July 1 2017 • 630 Bands • Metis and Inuit too British Columbia • Joined Canada in 1871 • 203 Bands The Nlaka’pamux Nation Archeology indicates an indigenous population living on the land for 7,000 years +. 1808: First Contact with French NWC with arrival of Simon Fraser. • First named Couteau Tribe. • Later renamed the Thompson Indian. 1857-58: Fought Americans to standstill in the Fraser Canyon War 1876: 69 villages amalgamated into 15 Indian Bands under the Indian Act 1878: Reserve Land allocations Kanaka Bar Indian Band • One of the original Nlaka’pamux communities. • Webpage: www.kanakabarband.ca • 66 members on reserve, 150 off • Codified: Election, Membership and Governance Codes in 2013. • Leadership: an indefinite term but face recall every 3rd Thursday. Land Use Plan (March 2015). Community Economic Development Plan (March 2016). Bi-annual implementation plans. Holistic: what one does affects another Kanaka Bar Indian Band Organization Chart As at May 2, 2016 Kanaka Bar & British Columbia Clean Energy Sectors Large Hydro Geothermal Tidal Wave N/A Applicable some day? N/A N/A Biomass Solar Run of River Wind Considered: not yet? 1.5 Projects 1.5 Projects Concept Stage How are we doing this? BC Hydro (the buyer of electrons) Self-sufficiency (off grid) Net Metering: projects under 100Kw Generating electrons for office, can connect to grid. -

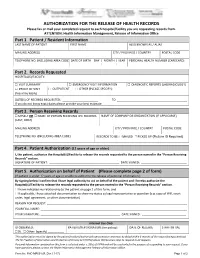

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

To Read an Excerpt from Claiming the Land

CONTENTS S List of Illustrations / ix Preface / xi INTRODUCTION Fraser River Fever on the Pacific Slope of North America / 1 CHAPTER 1 Prophetic Patterns: The Search for a New El Dorado / 13 CHAPTER 2 The Fur Trade World / 36 CHAPTER 3 The Californian World / 62 CHAPTER 4 The British World / 107 CHAPTER 5 Fortunes Foretold: The Fraser River War / 144 CHAPTER 6 Mapping the New El Dorado / 187 CHAPTER 7 Inventing Canada from West to East / 213 CONCLUSION “The River Bears South” / 238 Acknowledgements / 247 Appendices / 249 Notes / 267 Bibliography / 351 About the Author / 393 Index / 395 PREFACE S As a fifth-generation British Columbian, I have always been fascinated by the stories of my ancestors who chased “the golden butterfly” to California in 1849. Then in 1858 — with news of rich gold discoveries on the Fraser River — they scrambled to be among the first arrivals in British Columbia, the New El Dorado of the north. To our family this was “British California,” part of a natural north-south world found west of the Rocky Mountains, with Vancouver Island the Gibraltar-like fortress of the North Pacific. Today, the descendants of our gold rush ancestors can be found throughout this larger Pacific Slope region of which this history is such a part. My early curiosity was significantly moved by these family tales of adventure, my great-great-great Uncle William having acted as fore- man on many of the well-known roadways of the colonial period: the Dewdney and Big Bend gold rush trails, and the most arduous section of the Cariboo Wagon Road that traversed and tunnelled through the infamous Black Canyon (confronted by Simon Fraser just a little over 50 years earlier). -

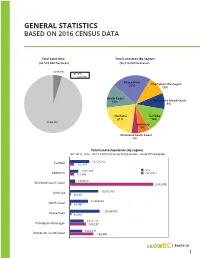

General Statistics Based on 2016 Census Data

GENERAL STATISTICS BASED ON 2016 CENSUS DATA Total Land Area Total Land Area (by region) (92,518,600 hectares) (92,518,600 hectares) 4,615,910 ALR non-ALR Peace River 22% Thompson-Okanagan 10% North Coast 13% Vancouver Island-Coast 9% Nechako Cariboo 21% 14% 87,902,700 Kootenay 6% Mainland-South Coast 4% Total Land & Population (by region) (BC total - Area - 92,518,600 (hectares) & Population - 4,648,055 (people)) Cariboo 13,128,585 156,494 5,772,130 Area Kootenay Population 151,403 3,630,331 Mainland-South Coast 2,832,000 19,202,453 Nechako 38,636 12,424,002 North Coast 55,500 20,249,862 Peace River 68,335 9,419,776 Thompson-Okanagan 546,287 8,423,161 Vancouver Island-Coast 799,400 GROW | bcaitc.ca 1 Total Land in ALR (etare by region) Total Nuber o ar (BC inal Report Number - 4,615,909 hectares) (BC total - 17,528) Cariboo 1,327,423 Cariboo 1,411 Kootenay 381,551 Kootenay 1,157 Mainland-South Coast 161,961 Mainland-South Coast 5,217 Nechako 747 Nechako 373,544 North Coast 116 North Coast 109,187 Peace River 1,335 Peace River 1,333,209 Thompson-Okanagan 4,759 Thompson-Okanagan 808,838 Vancouver Island-Coast 2,786 Vancouver Island-Coast 120,082 As the ALR has inclusions and exclusions throughout the year the total of the regional hectares does not equal the BC total as they were extracted from the ALC database at different times. Total Area o ar (etare) Total Gro ar Reeipt (illion) (BC total - 6,400,549) (BC total - 3,7294) Cariboo 1,160,536 Cariboo 1063 Kootenay 314,142 Kootenay 909 Mainland-South Coast 265,367 Mainland-South Coast 2,4352 -

MANAGING DISCORD in the AMERICAS Great Britain and the United States 1886-1896

MANAGING DISCORD IN THE AMERICAS Great Britain and the United States 1886-1896 GERER LA DISCORDE DANS LES AMERIQUES La Grande-Bretagne et les Etats-Unis 1886-1896 A Thesis Submitted To the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada By Charles Robertson Maier, CD, MA In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2010 ©This Thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69195-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-69195-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Farrell & Waatainen, 2020 Canadian Social Studies, Volume 51

Farrell & Waatainen, 2020 Canadian Social Studies, Volume 51, Issue No. 2 Face-to-Face with Place: Place-Based Education in the Fraser Canyon Teresa Farrell Instructor, Faculty of Education Vancouver Island University [email protected] Paula Waatainen Instructor, Faculty of Education Vancouver Island University [email protected] This work was supported by funding received from a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Exchange Grant, a Vancouver Island University Innovate Grant, and funds from the Faculty of Education, Vancouver Island University. Two instructors from the Faculty of Education at Vancouver Island University organized a three-day field experience with 35 pre-service teachers along the Fraser Canyon corridor, home of the Nlaka’pamux and Stó:lō Nations. We asked: How will an educational field experience in this place impact and inform pre-service teachers and researchers’ understanding of place- based education (PBE) in their practice? We explore the shift towards Indigenous perspectives that subtly wove its way through the work and how it framed new ways of thinking about place for our participants and new ways of considering decolonizing education for the instructor researchers. We conclude by arguing that PBE is necessitated by active, living relationship in place and provides opportunities for critical pedagogy grounded in Indigeneity. We also suggest that both Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators have a role to play in this work. “Is it not time to face place – to confront it, take off its veil and see its full face.” (Johnson and Murton, 2007, p. 127). On September 12, 2019, two instructor researchers traveled with 35 pre-service teachers to a place that lived in our minds and hearts: the Fraser Canyon corridor1, in what is now British Columbia, Canada. -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

Barkerville Gold Mines Ltd

BARKERVILLE GOLD MINES LTD. CARIBOO GOLD PROJECT AUGUST 2020 ABOUT THE CARIBOO GOLD PROJECT The Cariboo Gold Project includes: • An underground gold mine, surface concentrator and associated facilities near Wells The Project is located in the historic • Waste rock storage at Bonanza Ledge Mine Cariboo Mining District, an area where • A new transmission line from Barlow Substation to the mine site mining has been part of the landscape • Upgrades to the existing QR Mill and development of a filtered stack tailings since the Cariboo Gold Rush in the 1860s. facility at the QR Mill Site • Use of existing roads and development of a highway bypass before Wells The Project is being reviewed under the terms of the BC Environmental Assessment Act, 2018. CARIBOO GOLD PROJECT COMPONENTS • Underground mine and ore crushing • Water management and treatment CARIBOO GOLD • Bulk Fill Storage Area • New camp MINE SITE • Electrical substation • Offices, warehouse and shops in the • Above ground concentrator and paste concentrator building backfill plant • Mill upgrades for ore processing • Filtered stack tailings storage facility - no QR MILL SITE • New tailings dewatering (thickening tailings underwater and no dams and filtering) plant • New camp BONANZA LEDGE • Waste rock storage MINE • Movement of workers, equipment and • Concentrate transport to QR Mill via Highway TRANSPORTATION supplies via Highway 26, 500 Nyland 26 and 500 Nyland Lake Road. ROUTES Lake Road, Quesnel Hydraulic Road • New highway bypass before Wells (2700 Road) • Movement of waste -

Lillooet-Lytton Tourism Diversification Project

LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM PROJECT 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ..................................................................................4 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Terms of Reference............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Study Area Description...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Local Economic Challenges............................................................................................................................... 8 2. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TOURISM.....................................................................9 2.1 Tourism in British Columbia............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Nature-Based Tourism and Rural BC............................................................................................................