Indigenous Planning Perspectives Task Force Report's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

Indigenous Planning

Planning Theory & Practice ISSN: 1464-9357 (Print) 1470-000X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rptp20 Indigenous Planning: from Principles to Practice/ A Revolutionary Pedagogy of/for Indigenous Planning/Settler-Indigenous Relationships as Liminal Spaces in Planning Education and Practice/ Indigenist Planning/What is the Work of Non- Indigenous People in the Service of a Decolonizing Agenda?/Supporting Indigenous Planning in the City/Film as a Catalyst for Indigenous Community Development/Being Ourselves and Seeing Ourselves in the City: Enabling the Conceptual Space for Indigenous Urban Planning/Universities Can Empower the Next Generation of Architects, Planners, and Landscape Architects in Indigenous Design and Planning Libby Porter, Hirini Matunga, Leela Viswanathan, Lyana Patrick, Ryan Walker, Leonie Sandercock, Dana Moraes, Jonathan Frantz, Michelle Thompson-Fawcett, Callum Riddle & Theodore (Ted) Jojola To cite this article: Libby Porter, Hirini Matunga, Leela Viswanathan, Lyana Patrick, Ryan Walker, Leonie Sandercock, Dana Moraes, Jonathan Frantz, Michelle Thompson-Fawcett, Callum Riddle & Theodore (Ted) Jojola (2017) Indigenous Planning: from Principles to Practice/A Revolutionary Pedagogy of/for Indigenous Planning/Settler-Indigenous Relationships as Liminal Spaces in Planning Education and Practice/Indigenist Planning/What is the Work of Non-Indigenous People in the Service of a Decolonizing Agenda?/Supporting Indigenous Planning in the City/Film as a Catalyst for Indigenous Community Development/Being Ourselves and Seeing Ourselves in the City: Enabling the Conceptual Space for Indigenous Urban Planning/Universities Can Empower the Next Generation of Architects, Planners, and Landscape Architects in Indigenous Design and Planning, Planning Theory & Practice, 18:4, 639-666, DOI: 10.1080/14649357.2017.1380961 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1380961 Published online: 15 Nov 2017. -

Indigenous Community Planning: Ways of Being, Knowing and Doing DRAFT

PLAN 533: Indigenous Community Planning: ways of being, knowing and doing DRAFT 2019-20 Winter Term 1 Introductory session: Wed 11th Sept, 12.30 – 2pm, WMA 240 (All registered and waitlist students MUST attend this Intro class) Sept 28 and 29: 10am -5pm (Musqueam and UBC) Nov 2nd and 3rd : 10am – 5pm (Musqueam and UBC) Nov 23rd and 24th: 10am – 5pm (Musqueam and UBC) Instructors: Drs. Leonie Sandercock & Maggie Low (SCARP) + Dr. Leona Sparrow, Musqueam Indian Band/ SCARP Adjunct Professor, and other Musqueam knowledge holders. This course is a requirement for ICP students in SCARP, and is limited to 15 students. It is open to all SCARP students, and also to First Nations & Indigenous Studies students (300 and 400 level) who have met Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies requirements for taking graduate level courses, and to graduate students from other departments, depending on available space. See Registration form for details: http://www.grad.ubc.ca/forms/students/UndergradEnrol.pdf ATTENDANCE: 100% attendance is mandatory for this course. If you cannot commit to attending all six full days over the three weekends, you should not register for this course. Any half day absence will incur a 10% deduction from your final grade. (Exceptions of course for illness or emergency) Key words Indigenous world view; indigenous planning; Indigenous ways of knowing and governance systems; UNDRIP; comprehensive community planning (CCP); unceded territories; colonization; decolonization; contact zone; settler societies; respect, recognition, rights; traditional ecological knowledge; co-existence, reconciliation, partnership. Course Outline This course starts with acknowledging the history of colonization of Indigenous peoples in Canada, and asks if planning has been a part of that process. -

Sustainability and Indigenous Interests in Regional Land Use Planning: Case Study of the Peel Watershed Process in Yukon, Canada

Sustainability and Indigenous Interests in Regional Land Use Planning: Case Study of the Peel Watershed Process in Yukon, Canada by Emily Caddell A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Environment Studies in Environment and Resource Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2018 ©Emily Caddell 2018 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Canada’s northern territories, including the Yukon, are facing significant social, economic, political and ecological change. Devolution processes and comprehensive land claim agreements with self- governing First Nations have given rise to new land and resource decision making processes, including Regional Land Use Planning (RLUP). Project level Environmental Assessments (EAs) have been a main tool for governments to meet some of their fiduciary responsibilities to Indigenous peoples under Section 35 of Canada’s Constitution and to mitigate potentially adverse environmental impacts of non- renewable resource development projects. However, project level EAs are ill-equipped to address cumulative effects, regional conservation needs, broad alternatives and overall sustainability considerations central to Indigenous interests. RLUPs, if designed and authorized to guide project planning and assessment, are a more promising tool for addressing these interests, but how well they can serve both sustainability and Indigenous interests is not yet suitably demonstrated. RLUP processes established under comprehensive land claim agreements with First Nations in the Yukon enable cooperative decision-making about the future of the territory, including the pace and scale of non-renewable resource development and regions set aside for conservation. -

Chapters in Canadian Popular Music

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Ilona Šoukalová Chapters in Canadian Popular Music Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Chapters in Canadian Popular Music (Diplomová práce) Autor: Ilona Šoukalová Studijní obor: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Počet stran: 72 Počet znaků: 138 919 Olomouc 2015 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma "Chapters in Canadian Popular Music" vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 3.5.2015 Ilona Šoukalová Děkuji vedoucímu mé diplomové práce panu Mgr. Jiřímu Flajšarovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k práci. Poděkování patří také pracovníkům Ústřední knihovny Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci za pomoc při obstarávání pramenů a literatury nezbytné k vypracování diplomové práce. Děkuji také své rodině a kamarádům za veškerou podporu v době mého studia. Abstract The diploma thesis deals with the emergence of Canadian popular music and the development of music genres that enjoyed the greatest popularity in Canada. A significant part of the thesis is devoted to an investigation of conditions connected to the relation of Canadian music and Canadian sense of identity and uniqueness. Further, an account of Canadian radio broadcasting and induction of regulating acts which influenced music production in Canada in the second half of the twentieth century are given. Moreover, the effectiveness and contributions of these regulating acts are summarized and evaluated. Last but not least, the main characteristics of the music style of a female singer songwriter Joni Mitchell are examined. -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

Backgroundfile-83687.Pdf

Attachment TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Grants Impact Analysis ........................................................................................... 1 Overview Strategic Funding .................................................................................................................. 3 Arts Discipline Funding ......................................................................................................... 3 Assessment and Allocations Process ................................................................................... 4 Loan Fund ............................................................................................................................. 4 Operations ............................................................................................................................. 4 Preliminary Results of Increased Grants Funding ............................................................................. 6 2014 Allocations Summary ................................................................................................................ 7 Income Statement & Program Balances for the quarter ended December 31, 2014 ........................ 8 Strategic Funding 2014 Partnership Programs .......................................................................................................... 9 Strategic Partnerships ........................................................................................................... 10 Strategic Allocations ............................................................................................................. -

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ______

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ A Knowledge and Literature Review Prepared for the Research and Evaluaon Sec@on Canada Council for the Arts _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE TRÉPANIER & CHRIS CREIGHTON-KELLY December 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For more information, please contact: Research and Evaluation Section Strategic Initiatives 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566‐4414 / (800) 263‐5588 ext. 4261 [email protected] Fax (613) 566‐4430 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e Cette publication est aussi offerte en français Cover image: Hanna Claus, Skystrip(detail), 2006. Photographer: David Barbour Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review ISBN 978‐0‐88837‐201‐7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS! 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY! 4 Why a Literature Review?! 4 Steps Taken! 8 Two Comments on Terminology! 9 Parlez-vous français?! 10 The Limits of this Document! 11 INTRODUCTION! 13 Describing Aboriginal Arts! 15 Aboriginal Art Practices are Unique in Canada! 16 Aboriginal Arts Process! 17 Aboriginal Art Making As a Survival Strategy! 18 Experiencing Aboriginal Arts! 19 ABORIGINAL WORLDVIEW! 20 What is Aboriginal Worldview?! 20 The Land! 22 Connectedness! -

First Nation Community Planning in Saskatchewan, Canada

JPEXXX10.1177/0739456X15621147Journal of Planning Education and ResearchPrusak et al. 621147research-article2015 Research-Based Article Journal of Planning Education and Research 1 –11 Toward Indigenous Planning? © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav First Nation Community Planning DOI: 10.1177/0739456X15621147 in Saskatchewan, Canada jpe.sagepub.com S. Yvonne Prusak1, Ryan Walker2, and Robert Innes2 Abstract “Indigenous planning” is an emergent paradigm to reclaim historic, contemporary, and future-oriented planning approaches of Indigenous communities across western settler states. This article examines a community planning pilot project in eleven First Nation reserves in Saskatchewan, Canada. Qualitative analysis of interviews undertaken with thirty-six participants found that the pilot project cultivated the terrain for advancing Indigenous planning by First Nations, but also reproduced settler planning processes, authority, and control. Results point to the value of visioning Indigenous futures, Indigenous leadership and authority, and the need for institutional development. Keywords aboriginal, community planning, First Nation, Indigenous planning, reservation, reserve Introduction This article examines a multiyear community planning pilot project undertaken from 2006 to 2011 on the principal “Indigenous planning” is an emergent paradigm in contempo- reserves of eleven of those Saskatchewan First Nations. The rary planning discourse that aims to reclaim the historic, con- pilot project was an initiative of the federal government’s temporary, and future-oriented planning approaches of Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Indigenous communities across western settler states like Canada (AANDC). The planning consultant team hired by Canada, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia AANDC to undertake the pilot project with First Nations and (Jojola 2008; Matunga 2013; Walker, Jojola, and Natcher their affiliated tribal councils was the Cities and Environment 2013). -

Course Outlines

School of Community and Regional Planning (SCARP) University of British Columbia COURSE OUTLINE Course Number PLAN 221 Course Credit(s) 3 Course Title City Visuals Term 2017-2018 Day Friday Time 2:00 to 5:00pm Instructor Erick Villagomez Office WMAX 231 Telephone n/a Email [email protected] Office Hours TBD Short Course Description This course is an exploratory journey through the vast world of visualizing the city. Students will gain an understanding of the types and hierarchies of visualizations of the city and how to interpret them and use them to read the city. This course is open to all UBC students in 2nd year and above, regardless of prior experience. Course Format Course will meet twice a week for 1.5 hours each session. Course material will be structured using a combination of presentations and in-class exercises, discussions and tutorials. Class sessions will emphasize visual material, which will be guided by course instructors but also supplied, informed and analyzed by students. Students will see images, watch videos and listen to audio works about the city. Course Overview, Content and Objectives This course is an exploratory journey through the vast world of visualizing the city. How has our way of understanding and representing cities evolved from old parchment maps to dynamic real-time data capture with user-interactive visualizations of urban regions? How do we represent spatial data and what do we use, when and how? Broadly, students will gain a historical understanding of how the city has been represented visually, as well as the fundamentals of representation types and information design, in the service of reading and interpreting visualizations of the city. -

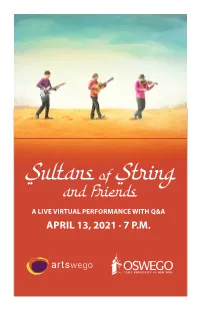

Virtual Program Is Brought to You by the Streaming Services of Entertainment Engineering Collective

a A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE WITH Q&A APRIL 13, 2021 · 7 P.M. Supporting the Arts at Oswego Made possible by the Student Arts Fee, administered by ARTSwego SUNY Oswego — Livestream interactive Zoom concert! Featured on the New York Times hits list and the Billboard World Music Charts! Sultans of String band members Chris McKhool, Kevin Laliberté and Drew Birston perform the Best of the Sultans, beamed right into your living room! Special guests include Ojibway Elder Duke Redbird, flamenco dancer and singer Tamar Ilana, JUNO Award-winning Hungarian pianist Robi Botos, Madagascar’s Donné Roberts and Yukiko Tsutsui from Japan! This is over Zoom, which is awesome because it is interactive, and we will be able to see and hear you, and you can see and hear us, and you can all see each other as well! It is a real show! So pour yourself a quarantini, and get ready to enjoy the music! The link becomes live at 6:40 p.m. to get settled and chat with our friends. And make sure you have speakers plugged in if you have them! The show will last about an hour, and then will feature a talkback portion, so bring your burning questions, as we will be opening up the floor for anyone who has always wanted to ask any of the artists about their inspiration, or music, or whatever strikes your fancy. Special guest performance by the SUNY Oswego’s Small Group Jazz The Girl from Ipanema Antônio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994) Ryan Zampella, Tenor Saxophone Brandon Schmitt, Guitar Benjamin Coddington, Piano Zachary Robison, Bass Robert Ackerman, Drum Set The State University of New York at Oswego would like to recognize with respect the Onondaga Nation, the “people of the hills,” or central firekeepers of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Indigenous peoples on whose ancestral lands SUNY Oswego now stands. -

ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor: 4.164 Refereed Journal ISSN -2395-1877

IJMDRR Research Paper E- ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor: 4.164 Refereed Journal ISSN -2395-1877 A STUDY OF SYMBOLS AND IMAGERY IN DUKE REDBIRD’S POEM I AM THE REDMAN WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO NORTHROP FRYE’S ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Rajalahshmi T Assistant Professor of English, PG & Research Department of English, Vellalar College for Women, Thindal. Abstract The study of the vast and rich body of the literature of the native people of Canada has been too long neglected and ignored. Very few literary scholars are familiar with the oral literature that transcends the European concepts of genre, or the written literature that spans a wide range of genres-speeches, letters, sermons, reports, petitions, diary entries, essays, history, journals, autobiography, poetry, short stories, and novels. Native poetry of Canada lagged behind prose in the 1970s. Among the poets who managed to get published their poems were Sarain Stump, Duke Redbird, George Kenny, Rita Joe, Ben Abel, Chief Dan George, and Daniel David Moses. Sarain Stump in his poem There is My People Sleeping laments at the loss of the traditional way of life while Duke Redbird in his poem, ‘I Am the Redman’ lashes out against an insensitive white society which reflects the political turmoil of the period when he was a militant social activist. Penne Petrone in her work Native Literature in Canada from the Oral Tradition to the Present has criticized, “In ‘I Am the Redman’ Redbird’s ironic tone and symbolism, derived from an urban and industrialized society, bristle with contempt and pride” (130). The paper aims to compare the symbols occur in ‘I Am the Redman’ with the archetypal symbols found in mythology and literature with special reference to the Canadian critic Northrop Frye’s, Anatomy of Criticism.