A Contribution to the Natural History of the Sparrow Hawk, Falco Sparverius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egg Investment Strategies Adopted by a Desertic Passerine, the Saxaul

Bao et al. Avian Res (2020) 11:15 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00201-0 Avian Research RESEARCH Open Access Egg investment strategies adopted by a desertic passerine, the Saxaul Sparrow (Passer ammodendri) Xinkang Bao1* , Wei Zhao1, Fangqing Liu2, Jianliang Li1 and Donghui Ma1 Abstract Background: As one of the reproductive strategies adopted by bird species, variation in investment in egg produc- tion and its infuencing factors are important and well-studied subjects. Intraclutch changes in egg size associated with laying order may refect a strategy of “brood survival” or “brood reduction” adopted by female birds in diferent situations. Methods: We conducted feld studies on the breeding parameters of the Saxaul Sparrow (Passer ammodendri) in Gansu Province, China from 2010 to 2017, to clarify the factors afecting the egg investment and reproductive perfor- mance of this passerine species. Results: Our results revealed signifcant diferences in clutch size, egg size and the fedging rate between the frst and second brood of Saxaul Sparrows and suggested that this typical desert species allocates more breeding resources to the more favourable second brood period, leading to greater reproductive output. Female body size pre- sented a positive relationship with egg size, and male body size presented positive relationships with clutch size and hatchability. The females that started their clutches later laid more eggs, and hatchability and the fedging rate also increased with a later laying date in the frst brood period. With successive eggs laid within the 5-egg clutches (the most frequent clutch size), egg size increased for the frst three eggs and then signifcantly decreased. -

AERC Wplist July 2015

AERC Western Palearctic list, July 2015 About the list: 1) The limits of the Western Palearctic region follow for convenience the limits defined in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic” (BWP) series (Oxford University Press). 2) The AERC WP list follows the systematics of Voous (1973; 1977a; 1977b) modified by the changes listed in the AERC TAC systematic recommendations published online on the AERC web site. For species not in Voous (a few introduced or accidental species) the default systematics is the IOC world bird list. 3) Only species either admitted into an "official" national list (for countries with a national avifaunistic commission or national rarities committee) or whose occurrence in the WP has been published in detail (description or photo and circumstances allowing review of the evidence, usually in a journal) have been admitted on the list. Category D species have not been admitted. 4) The information in the "remarks" column is by no mean exhaustive. It is aimed at providing some supporting information for the species whose status on the WP list is less well known than average. This is obviously a subjective criterion. Citation: Crochet P.-A., Joynt G. (2015). AERC list of Western Palearctic birds. July 2015 version. Available at http://www.aerc.eu/tac.html Families Voous sequence 2015 INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME remarks changes since last edition ORDER STRUTHIONIFORMES OSTRICHES Family Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus ORDER ANSERIFORMES DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor cat. A/D in Morocco (flock of 11-12 suggesting natural vagrancy, hence accepted here) Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica cat. -

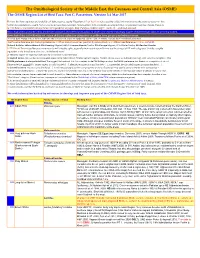

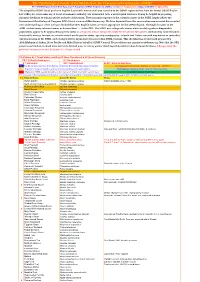

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a Field Checklist

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a field checklist Black-throated Sparrow by Kelly B. Bryan Birds of the Trans-Pecos: a field checklist the chihuahuan desert Traditionally thought of as a treeless desert wasteland, a land of nothing more than cacti, tumbleweeds, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes – West Texas is far from it. The Chihuahuan Desert region of the state, better known as the Trans-Pecos of Texas (Fig. 1), is arguably the most diverse region in Texas. A variety of habitats ranging from, but not limited to, sanddunes, desert-scrub, arid canyons, oak-juniper woodlands, lush riparian woodlands, plateau grasslands, cienegas (desert springs), pinyon-juniper woodlands, pine-oak woodlands and montane evergreen forests contribute to a diverse and complex avifauna. As much as any other factor, elevation influences and dictates habitat and thus, bird occurrence. Elevations range from the highest point in Texas at 8,749 ft. (Guadalupe Peak) to under 1,000 ft. (below Del Rio). Amazingly, 106 peaks in the region are over 7,000 ft. in elevation; 20 are over 8,000 ft. high. These montane islands contain some of the most unique components of Texas’ avifauna. As a rule, human population in the region is relatively low and habitat quality remains good to excellent; habitat types that have been altered the most in modern times include riparian corridors and cienegas. Figure 1: Coverage area is indicated by the shaded area. This checklist covers all of the area west of the Pecos River and a corridor to the east of the Pecos River that contains areas of Chihuahuan Desert habitat types. -

The House Sparrow Is Disappearing from Many of Our Cities and Towns

AKHILESH KUMAR, AMITA KANAUJIA, SONIKA KUSHWAHA AND ADESH KUMAR TORY S OVER C The House sparrow is disappearing from many of our cities and towns. We can resurrect their numbers by simple steps like providing alternative nesting sites for these little chirping birds. among the fi rst animals to develop a close surveys conducted by ornithologists and association with humans. This led it to researchers suggest that the dramatic HE gentle chirruping of the small bird being given the name Passer domesticus. decline in population of the sparrow is an Tis slowly vanishing. As the House The House sparrow is also commonly unfortunate reality. sparrow loses its living space to other known as Gauriya. Scientists and researchers aggressive birds and also to humans, it is Unfortunately, the species has been suggest several causes responsible disappearing in large parts of the world. declining since the early 1980s in several for the diminishing population like In the last few years the bird has gone parts of the world. There has also been unavailability of nesting space, decrease completely missing from most urban noticeable decline in the number of in food availability, changes in human neighbourhoods. House sparrows in several parts of India lifestyle, pollution, electromagnetic As humans settled down to particularly across Bangalore, Mumbai, radiation from mobile phone towers agriculture and set up permanent Hyderabad, Punjab, Haryana, West (obsolete theory now) and diseases. settlements, the House sparrow was Bengal, Delhi and other cities. Several -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

TURKMENISTAN - ULTIMATE CENTRAL ASIA BIRDING with MIKSTURE 20.Th April – 5.Th May 2014

TURKMENISTAN - ULTIMATE CENTRAL ASIA BIRDING WITH MIKSTURE 20.th April – 5.th May 2014 Welcome to the ultimate desert and mountain birding in Turkmenistan - Central Asian birding when it’s best! Turkmenistan provides the best desert birding in central Asia! That’s one of the reasons Turkmenistan has become a popular Miksture destination in Central Asia. The Desert and Kopet Dag Mountains provides the most prolific and rewarding birding amidst unsurpassed beautiful scenery. Some of the most wanted spe- cies known as “dream-species” makes it an essential destination for anyone with a serious interest in Pale- arctic birds. In addition there is a great selection of species present in Southern Europe, interesting subspe- cies as many European birds are on the edge of their eastern range here and migrants makes the birding impressive and challenging. Miksture is a pioneer in Turkmenistan birding and knows thoroughly the loca- tions and where the birds occur. We have done these areas for years, and we continue to improve and keep the route updated, so our clients get the best logistic and itinerary – in short: the best and most re- warding birding. Our team provides good meals, and we always make the journey as comfortable and smooth as possible. We don’t make any compromises when it’s about finding the birds, however we always make priority not to flush and frighten the birds. Time of year is perfect! Tour start: In Copenhagen, Denmark 20.th April 2013, or Ashgabat 21.th April 2014. Departure from other countries is of course possible, and to meet in Istanbul or Ashgabat. -

Fifth Report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee - 2018

Fifth report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee - 2018 by the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee: Frédéric Jiguet and Lukasz Lawicki (secretaries), Sherif Baha El Din (chairman), Andrea Corso, Pierre- André Crochet, Richard Hoath, Manuel Schweizer & Ahmed Waheed Released 25 th January 2019 Citation: Jiguet F., Lawicki L., Baha El Din S., Corso A., Crochet P.-A., Hoath R., Schweizer M. & Wahhed A. (2019) Fifth report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee – 2018. The Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee (EORC) was launched in January 2010 to become the adjudicator of rare bird records for Egypt and to maintain the list of the bird species of Egypt. In 2018, the EORC was composed of 8 active voting members: Sherif Baha El Din, Andrea Corso, Pierre-André Crochet, Richard Hoath, Frédéric Jiguet, Lukasz Lawicki, Manuel Schweizer and Ahmed Waheed. Any observer recording a rare bird in Egypt (e.g. species on the EORC list or not listed in the updated national checklist) is invited to send details to the secretary ([email protected]) to help maintain the official national avifaunal list. As stated in its first report (Jiguet et al. 2011), the EORC decided to use the checklist of the Birds of Egypt, as published in 1989 by Steve Goodman and Peter Meininger (excluding the hypothetical species) as a starting point to its work. Any addition to, or deletion from, this list will be evaluated by the EORC, as well as any record of species with less than 10 Egyptian records (see http://www.chn-france.org/eorc/eorc.php?id_content=4 for the full list of species to be documented) and any change in category (e.g. -

Marvelous Morocco: North Africa in a Nutshell March 2019

Tropical Birding Trip Report Marvelous Morocco: North Africa in a Nutshell March 2019 A Tropical Birding set departure tour Marvelous Morocco: North Africa in a Nutshell 23rd – 31st March 2019 Tour Leader: Emma Juxon All photographs in this report were taken by Emma Juxon, species depicted in photographs are named in BOLD RED Bird of the Trip: Northern Bald Ibis www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Marvelous Morocco: North Africa in a Nutshell March 2019 Introduction Morocco is a captivating destination; its mesmerizing landscapes, charming people and world-class cuisine will have you hooked – not to mention the birds. Increasing in popularity with many birders, it is quickly becoming the go-to place for Spring birding for a chance to see the Afro-European migration and the many near-endemic species found here. We encounter an ever-changing landscape on this tour, starting in the hustle and bustle of Marrakech, we leave the hectic city behind us as we make our way to the breathtaking mountainous panoramas of the High Atlas. Following the winding roads of the Tizi-n-Tichka pass we are transported to the stony desert of the Boumalne Dades area and on to the impressive Erg Chebbi, the ochra sands of the Sahara. From this desert oasis we pass through the up-and-coming city of Ouarzazate and on to the contrasting fertile coastal habitat surrounding Agadir before returning to Marrakech to indulge in a little culture. Each landscape provided us with a wealth of birds, from Levaillant’s Woodpecker and Crimson-winged Finch in the mountains, showy wheatears, wagtails and Cream-coloured Coursers in Boumalne Dades, striking Blue Rock Thrush of the Todra Gorge and everyone’s favorite the menagerie of desert dwelling species of Erg Chebbi, including Egyptian Nightjar, Desert Sparrow, African Desert Warbler and the incredible Pharaoh Eagle Owl. -

A Revised Multilocus Phylogeny of Old World Sparrows (Aves: Passeridae)

Vertebrate Zoology 71, 2021, 353–366 | DOI 10.3897/vz.71.e65952 353 A revised multilocus phylogeny of Old World sparrows (Aves: Passeridae) Martin Päckert1, Jens Hering2, Abdelkrim Ait Belkacem3, Yue-Hua Sun4, Sabine Hille5, Davaa Lkhagvasuren6, Safiqul Islam1, Jochen Martens7 1 Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden, Museum of Zoology, Königsbrücker Landstraße 159, 01109 Dresden, Germany 2 Verein Sächsischer Ornithologen e.V., 09212 Limbach-Oberfrohna, Germany 3 Laboratoire d’Exploration et de Valorisation des Écosystèmes Steppiques, Faculté des Sciences de la nature et de la vie, Université de Djelfa, Djelfa, Algeria 4 Key Laboratory of Animal Ecology and Conservation, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 5 Institute of Wildlife Biology and Game Management (IWJ), University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Gregor-Mendel-Straße 33, 1180 Vienna, Austria 6 Department of Biology, School of Arts and Sciences, National University of Mongolia, P.O.Box 46A-546, Ulaanbaatar-210646, Mongolia 7 Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution (iomE), Johannes Gutenberg University, 55099 Mainz, Germany http://zoobank.org/5C48BDBC-3761-4766-9E32-0C431F689992 Corresponding author: Martin Päckert ([email protected]) Academic editor Uwe Fritz | Received 15 March 2021 | Accepted 13 May 2021 | Published 31 May 2021 Citation: Päckert, M, Hering J, Belkacem AA, Sun Y-H, Hille S, Lkhagvasuren D, Islam S, Martens J (2021) A revised multilocus phylogeny of Old World sparrows (Aves: Passeridae). Vertebrate Zoology 71: 353–366. https://doi.org/10.3897/vz.71.e65952 Abstract The Old World sparrows include some of the best-studied passerine species, such as the cosmopolitan human commensal, the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) as well as poorly studied narrow-range endemics like the Iago sparrow (P. -

Passer Domesticus): Effects of Temperature, Rainfall, and Humidity

Turk J Zool 34 (2010) 255-266 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-0811-22 Clutch and egg size variation, and productivity of the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus): effects of temperature, rainfall, and humidity Aziz ASLAN1,*, Mustafa YAVUZ2 1Akdeniz University, Faculty of Education, Department of Primary Education, 07058 Antalya - TURKEY 2Akdeniz University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Biology, 07058 Antalya - TURKEY Received: 28.11.2008 Abstract: This study was conducted on the campus of the regional department of the forestry service, encompassing 2.25 ha in Antalya city center. The area has gardens and is surrounded by trees, providing nesting and feeding opportunities for many songbird species. The study aimed to determine clutch and egg size variation, breeding success, and productivity of the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus), in terms of clutch size and breeding attempts, and to evaluate variation in temperature, rainfall, and humidity in terms of breeding attempts and years, and their possible effects on given parameters of the species. In total, 2016 eggs were laid in 393 clutches and clutch size varied from 1 to 11 eggs; the clutches most commonly contained 4-6 egg in the 3 consecutive years. Mean egg length, width, weight, volume, and sphericity index were 21.16 ± 0.03 mm, 14.99 ± 0.01 mm, 2.02 ± 0.01 g, 2.38 ± 0.01 cm3, and 71.01 ± 0.09, respectively. Breeding attempts were affected by temperature (r = 0.97 P < 0.0001) and rainfall (r = −0.84 P < 0.001). Egg length was affected by rainfall (r = 0.60 P < 0.041), humidity (r = 0.59 P < 0.044), and temperature (r = −0.81 P < 0.002), and egg volume was affected by temperature (r = −0.68 P < 0.015). -

Dakhla Trip Report

Birding Trip to the Bay of Dakhla and Aousserd region By Javi Elorriaga and Yeray Seminario / Birding The Strait February 2016 The immense Bay of Dakhla is set against tall Sand Dunes that make this place unique In autumn 2015 we were asked by Dakhla Attitude Hotel, to scout the area and assess the possibilities to accommodate birding and nature enthusiasts’ groups during trips to the Atlantic Sahara. We scheduled the trip for the middle of February 2016, which is a good time for birding in the area both in terms of phenology and weather. Following the expansion of the Dakhla airport and the current sociopolitical stability in the area, the interest of Dakhla as an international touristic destination has significantly grown over the last years. Nowadays it constitutes a very popular destination for international surfers. Besides, recent pioneering birding and wildlife trips to the Bay of Dakhla and Aousserd region are increasing, resulting in regular records of new or very scarce species of birds and mammals for the Western Paleartic region, sometimes in unprecedented numbers. Birding The Strait - Nº RTA: AT/CA/00311 - birdingthestrait.com - [email protected] 1 Some of the most significant species include: Sudan Golden Sparrow, Golden Nightjar, Cricket Longtail, Black-crowned Sparrow-Lark, Dunn´s Lark, African Royal Tern, Kelp Gull and Namaqua Dove among birds; and African Golden Wolf, Fennec, Sand Cat, Rüppell´s Fox, Ratel, Orca and Atlantic Humpbacked dolphin among mammals. No doubt, the discovery of highly attractive species of wildlife will keep growing in forthcoming years making of the Dakhla region a top destination for international nature enthusiasts.