Egg Investment Strategies Adopted by a Desertic Passerine, the Saxaul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rare Birds in Iran in the Late 1960S and 1970S

Podoces, 2008, 3(1/2): 1–30 Rare Birds in Iran in the Late 1960s and 1970s DEREK A. SCOTT Castletownbere Post Office, Castletownbere, Co. Cork, Ireland. Email: [email protected] Received 26 July 2008; accepted 14 September 2008 Abstract: The 12-year period from 1967 to 1978 was a period of intense ornithological activity in Iran. The Ornithology Unit in the Department of the Environment carried out numerous surveys throughout the country; several important international ornithological expeditions visited Iran and subsequently published their findings, and a number of resident and visiting bird-watchers kept detailed records of their observations and submitted these to the Ornithology Unit. These activities added greatly to our knowledge of the status and distribution of birds in Iran, and produced many records of birds which had rarely if ever been recorded in Iran before. This paper gives details of all records known to the author of 92 species that were recorded as rarities in Iran during the 12-year period under review. These include 18 species that had not previously been recorded in Iran, a further 67 species that were recorded on fewer than 13 occasions, and seven slightly commoner species for which there were very few records prior to 1967. All records of four distinctive subspecies are also included. The 29 species that were known from Iran prior to 1967 but not recorded during the period under review are listed in an Appendix. Keywords: Rare birds, rarities, 1970s, status, distribution, Iran. INTRODUCTION Eftekhar, E. Kahrom and J. Mansoori, several of whom quickly became keen ornithologists. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

A Systematic Ornithological Study of the Northern Region of Iranian Plateau, Including Bird Names in Native Language

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library European Journal of Experimental Biology, 2012, 2 (1):222-241 ISSN: 2248 –9215 CODEN (USA): EJEBAU A systematic ornithological study of the Northern region of Iranian Plateau, including bird names in native language Peyman Mikaili 1, (Romana) Iran Dolati 2,*, Mohammad Hossein Asghari 3, Jalal Shayegh 4 1Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran 2Islamic Azad University, Mahabad branch, Mahabad, Iran 3Islamic Azad University, Urmia branch, Urmia, Iran 4Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture and Veterinary, Shabestar branch, Islamic Azad University, Shabestar, Iran ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT A major potation of this study is devoted to presenting almost all main ornithological genera and species described in Gilanprovince, located in Northern Iran. The bird names have been listed and classified according to the scientific codes. An etymological study has been presented for scientific names, including genus and species. If it was possible we have provided the etymology of Persian and Gilaki native names of the birds. According to our best knowledge, there was no previous report gathering and describing the ornithological fauna of this part of the world. Gilan province, due to its meteorological circumstances and the richness of its animal life has harbored a wide range of animals. Therefore, the nomenclature system used by the natives for naming the animals, specially birds, has a prominent stance in this country. Many of these local and dialectal names of the birds have been entered into standard language of the country (Persian language). The study has presented majority of comprehensive list of the Gilaki bird names, categorized according to the ornithological classifications. -

AERC Wplist July 2015

AERC Western Palearctic list, July 2015 About the list: 1) The limits of the Western Palearctic region follow for convenience the limits defined in the “Birds of the Western Palearctic” (BWP) series (Oxford University Press). 2) The AERC WP list follows the systematics of Voous (1973; 1977a; 1977b) modified by the changes listed in the AERC TAC systematic recommendations published online on the AERC web site. For species not in Voous (a few introduced or accidental species) the default systematics is the IOC world bird list. 3) Only species either admitted into an "official" national list (for countries with a national avifaunistic commission or national rarities committee) or whose occurrence in the WP has been published in detail (description or photo and circumstances allowing review of the evidence, usually in a journal) have been admitted on the list. Category D species have not been admitted. 4) The information in the "remarks" column is by no mean exhaustive. It is aimed at providing some supporting information for the species whose status on the WP list is less well known than average. This is obviously a subjective criterion. Citation: Crochet P.-A., Joynt G. (2015). AERC list of Western Palearctic birds. July 2015 version. Available at http://www.aerc.eu/tac.html Families Voous sequence 2015 INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME remarks changes since last edition ORDER STRUTHIONIFORMES OSTRICHES Family Struthionidae Ostrich Struthio camelus ORDER ANSERIFORMES DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS Family Anatidae Fulvous Whistling Duck Dendrocygna bicolor cat. A/D in Morocco (flock of 11-12 suggesting natural vagrancy, hence accepted here) Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica cat. -

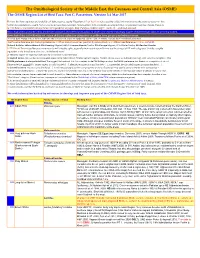

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a Field Checklist

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a field checklist Black-throated Sparrow by Kelly B. Bryan Birds of the Trans-Pecos: a field checklist the chihuahuan desert Traditionally thought of as a treeless desert wasteland, a land of nothing more than cacti, tumbleweeds, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes – West Texas is far from it. The Chihuahuan Desert region of the state, better known as the Trans-Pecos of Texas (Fig. 1), is arguably the most diverse region in Texas. A variety of habitats ranging from, but not limited to, sanddunes, desert-scrub, arid canyons, oak-juniper woodlands, lush riparian woodlands, plateau grasslands, cienegas (desert springs), pinyon-juniper woodlands, pine-oak woodlands and montane evergreen forests contribute to a diverse and complex avifauna. As much as any other factor, elevation influences and dictates habitat and thus, bird occurrence. Elevations range from the highest point in Texas at 8,749 ft. (Guadalupe Peak) to under 1,000 ft. (below Del Rio). Amazingly, 106 peaks in the region are over 7,000 ft. in elevation; 20 are over 8,000 ft. high. These montane islands contain some of the most unique components of Texas’ avifauna. As a rule, human population in the region is relatively low and habitat quality remains good to excellent; habitat types that have been altered the most in modern times include riparian corridors and cienegas. Figure 1: Coverage area is indicated by the shaded area. This checklist covers all of the area west of the Pecos River and a corridor to the east of the Pecos River that contains areas of Chihuahuan Desert habitat types. -

The House Sparrow Is Disappearing from Many of Our Cities and Towns

AKHILESH KUMAR, AMITA KANAUJIA, SONIKA KUSHWAHA AND ADESH KUMAR TORY S OVER C The House sparrow is disappearing from many of our cities and towns. We can resurrect their numbers by simple steps like providing alternative nesting sites for these little chirping birds. among the fi rst animals to develop a close surveys conducted by ornithologists and association with humans. This led it to researchers suggest that the dramatic HE gentle chirruping of the small bird being given the name Passer domesticus. decline in population of the sparrow is an Tis slowly vanishing. As the House The House sparrow is also commonly unfortunate reality. sparrow loses its living space to other known as Gauriya. Scientists and researchers aggressive birds and also to humans, it is Unfortunately, the species has been suggest several causes responsible disappearing in large parts of the world. declining since the early 1980s in several for the diminishing population like In the last few years the bird has gone parts of the world. There has also been unavailability of nesting space, decrease completely missing from most urban noticeable decline in the number of in food availability, changes in human neighbourhoods. House sparrows in several parts of India lifestyle, pollution, electromagnetic As humans settled down to particularly across Bangalore, Mumbai, radiation from mobile phone towers agriculture and set up permanent Hyderabad, Punjab, Haryana, West (obsolete theory now) and diseases. settlements, the House sparrow was Bengal, Delhi and other cities. Several -

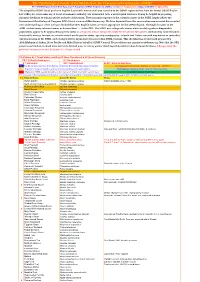

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

TURKMENISTAN - ULTIMATE CENTRAL ASIA BIRDING with MIKSTURE 20.Th April – 5.Th May 2014

TURKMENISTAN - ULTIMATE CENTRAL ASIA BIRDING WITH MIKSTURE 20.th April – 5.th May 2014 Welcome to the ultimate desert and mountain birding in Turkmenistan - Central Asian birding when it’s best! Turkmenistan provides the best desert birding in central Asia! That’s one of the reasons Turkmenistan has become a popular Miksture destination in Central Asia. The Desert and Kopet Dag Mountains provides the most prolific and rewarding birding amidst unsurpassed beautiful scenery. Some of the most wanted spe- cies known as “dream-species” makes it an essential destination for anyone with a serious interest in Pale- arctic birds. In addition there is a great selection of species present in Southern Europe, interesting subspe- cies as many European birds are on the edge of their eastern range here and migrants makes the birding impressive and challenging. Miksture is a pioneer in Turkmenistan birding and knows thoroughly the loca- tions and where the birds occur. We have done these areas for years, and we continue to improve and keep the route updated, so our clients get the best logistic and itinerary – in short: the best and most re- warding birding. Our team provides good meals, and we always make the journey as comfortable and smooth as possible. We don’t make any compromises when it’s about finding the birds, however we always make priority not to flush and frighten the birds. Time of year is perfect! Tour start: In Copenhagen, Denmark 20.th April 2013, or Ashgabat 21.th April 2014. Departure from other countries is of course possible, and to meet in Istanbul or Ashgabat. -

Fifth Report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee - 2018

Fifth report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee - 2018 by the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee: Frédéric Jiguet and Lukasz Lawicki (secretaries), Sherif Baha El Din (chairman), Andrea Corso, Pierre- André Crochet, Richard Hoath, Manuel Schweizer & Ahmed Waheed Released 25 th January 2019 Citation: Jiguet F., Lawicki L., Baha El Din S., Corso A., Crochet P.-A., Hoath R., Schweizer M. & Wahhed A. (2019) Fifth report of the Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee – 2018. The Egyptian Ornithological Rarities Committee (EORC) was launched in January 2010 to become the adjudicator of rare bird records for Egypt and to maintain the list of the bird species of Egypt. In 2018, the EORC was composed of 8 active voting members: Sherif Baha El Din, Andrea Corso, Pierre-André Crochet, Richard Hoath, Frédéric Jiguet, Lukasz Lawicki, Manuel Schweizer and Ahmed Waheed. Any observer recording a rare bird in Egypt (e.g. species on the EORC list or not listed in the updated national checklist) is invited to send details to the secretary ([email protected]) to help maintain the official national avifaunal list. As stated in its first report (Jiguet et al. 2011), the EORC decided to use the checklist of the Birds of Egypt, as published in 1989 by Steve Goodman and Peter Meininger (excluding the hypothetical species) as a starting point to its work. Any addition to, or deletion from, this list will be evaluated by the EORC, as well as any record of species with less than 10 Egyptian records (see http://www.chn-france.org/eorc/eorc.php?id_content=4 for the full list of species to be documented) and any change in category (e.g. -

Bird Watching Tour in Mongolia 2019

Mongolia 18 May – 09 June 2019 Bart De Keersmaecker, Daniel Hinckley, Filip Bogaert, Joost Mertens, Mark Van Mierlo, Miguel Demeulemeester and Paul De Potter Leader: Bolormunkh Erdenekhuu male Black-billed Capercaillie – east of Terelj, Mongolia Report by: Bart, Mark, Miguel, Bogi Pictures: everyone contributed 2 Introduction In 3 weeks, tour we recorded staggering 295 species of birds, which is unprecedented by similar tours!!! Many thanks to Wouter Faveyts, who had to bail out because of work related matters, but was a big inspiration while planning the trip. The Starling team, especially Johannes Jansen for careful planning and adjusting matters to our needs. Last but not the least Bolormunkh aka Bogi and his crew of dedicated people. The really did their utmost best to make this trip one of the best ever. Intinerary Day 1. 18th May Arrival 1st group at Ulaanbaatar. Birding along the riparian forest of Tuul river Day 2. 19th May Arrival 2nd part of group. Drive to Dalanzadgad Day 3. 20th May Dalanzadgad area Day 4. 21st May Shivee Am and Yolyn Am Gorges Day 5. 22nd May Yolyn Am Gorge, to Khongoryn Els Day 6. 23rd May Khongoryn Els and Orog Nuur Day 7. 24th May Orog Nuur, Bogd and Kholbooj Nuur Day 8. 25th May Kholbooj Nuur Day 9. 26th May Kholbooj Nuur and drive to Khangai mountain Day 10. 27th May Khangai mountain, drive to Tuin River Day 11. 28th May Khangai mountain drive to Orkhon River Day 12. 29th May Taiga forest Övörhangay and Arhangay Day 13. 30th May Khangai taiga forest site 2 Day 14. -

Mongolia - Birding in the Steppes of Genghis Khan

Mongolia - Birding in the Steppes of Genghis Khan Naturetrek Tour Report 4 - 19 June 2017 Amur Falcon Siberian Meadow Bunting White-crowned Penduline Tit Steppe Eagle Report and images by Alan Curry Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Mongolia - Birding in the Steppes of Genghis Khan Tour participants: Alan Curry (leader) with six Naturetrek clients Summary The tour proved a great success with generally smooth logistics, comfortable ger camps, exceedingly clement weather and some top-notch birding. We were fortunate not only to connect with but also see extremely well most of the regional specialities including Swan Goose, Black-billed Capercaillie, White-naped Crane, Siberian White Crane, Asian Dowitcher, Oriental Plover, Pallas's Gull, Pallas's Sandgrouse, Ural Owl, Saker, Henderson's Ground Jay, Siberian Rubythroat, Kozlov's Accentor, Azure Tit and Long-tailed Rosefinch. However it was not just about the birds, as almost every day was spent amongst simply fabulous scenic splendour! Day 1 Sunday 4th June The tour started with flights from the UK to Ulaanbaatar via Moscow, thankfully all pretty seamless and hiccup- free, with all our luggage arriving intact. A good positive start to the tour! Day 2 Monday 5th June Arriving in Ulaanbaatar (UB) around 6am, we soon cleared the airport formalities and met up with our local guide Odkhuu and his friendly team, seeing our first Pacific Swifts over the airport car park in the process. After meeting up with Sally, our Antipodean group member who had found her way independently to UB, we were soon heading out of the city bound for Terelj National Park, situated a couple of hours drive to the north-east of the city.