DOCUMENT Language Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Music of Ernst Toch

THE CHORAL MUSIC OF ERNST TOCH By MIRIAM SUSAN ZACH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTL^L FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1993 Copyright 1993 by Miriam Susan Zach ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to Mikesch Miicke, life-partner and architect, for his patience, encouragement, and introduction to Venturi's thought. His ability to clarify mysteries of computers and the German language made this dissertation a reaUty. She would like to express her deepest gratitude to her parents, Margaret Munster Zach and Herbert William Zach, for a lifetime of support and for advocating the research, teaching, and performance of music. She feels fortunate to have had the opportunity to study music history and Uterature wdth Dr. David Z. Kushner, a master teacher, pianist, and researcher, a mentor who cares. The author is grateful to Dr. Otto W. Johnston for his persistence to help her develop a cogent argument, for responding promptly with thoughtful insights that focused fragmentary ideas, and his humor during the long process. She would also like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Budd Udell, Dr. Arthur Jennings, Dr. PhyUis Dorman, Dr. Russell Robinson, and Professor Reid Poole for their counsel and collective effort to teach her how to fish. She would like to honor Dr. Robert and MilUe Ramey for their encouraging presence and thoughtfulness. Marsha Berman and Stephen Fry at the UCLA Toch Archive gave their time and expertise during the author's two visits to the collection, and made long-distance research possible. -

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Esperanto Parolata... Esperanto Parolata

speranto U S Bi-monthly bulletin published by the Esperanto League for North America 2006/3-4 Dumonata bulteno eldonata de la Esperanto-Ligo por Norda Ameriko 2006/3-4 En la Numero Esperanto parolata... Esperanto parolata... ¥enja Amis sur la trotuaroj de Novjorko! . 3-5 ELNA-kongreso 2007 . 5 Raporto el la Granda Pomo . 6 "Rigardu, oni ¤i tie piediras pli rapide ol en Atlanto!" Tio estis nia EKS – 10-jara!. 7 Nova ELNA-direktoro ser¤ata . 8 unua malkovro pri Novjorko. En Atlanto oni ne rapidas: oni Ùatas Pasporto al la Tuta Mondo saluti kaj babili kun nekonatoj sur stratoj kaj en transporto, kaj se en la Televido . 8 Recenze: Historical Fantasy... oni vidas ke vi venis de alia lando, oni tuj demandos vin mil kaj unu About Volapük. 9 demandojn. Atlanto estas ¤armo, kaj Novjorko estas ritmo. Ïi kap- Esperanto ¤e Seatla Foiro . 10 Esperanto-kurso en Atlanto . 10 tas vin en sian fluon, portas laª la rektaj stratoj kaj longaj avenuoj, Kiel organizi kongreson . 11 igas vian koron bati en la sama rapida ritmo de la urbega vivo. New from the Book Service . 12 Originala Poezio . 13 (Interesa malkovro: fine de la intensega kongresa semajno mi kon- Schön Schreiben . 14-15 statis ke ankaª mi komencis paroli pli rapide kaj pli ofte rigardi al La Elefantido . 16-18 Pacaj Hajkoj . 19 la horloßo.) Ãi tie oni ne parolas al nekonatoj, tamen, se vi perdißis Universala Vivokodo. 19 aª ne scias la vojon, oni afable helpos. En Novjorko neniu surpriz- Rozkruca Kontribuo al Paco . 19 ißus aªdante Esperanton surstrate: ja en tiu ¤i urbo oni parolas Deklaracio Pri Homaj Devoj . -

GRAMMAR of SOLRESOL Or the Universal Language of François SUDRE

GRAMMAR OF SOLRESOL or the Universal Language of François SUDRE by BOLESLAS GAJEWSKI, Professor [M. Vincent GAJEWSKI, professor, d. Paris in 1881, is the father of the author of this Grammar. He was for thirty years the president of the Central committee for the study and advancement of Solresol, a committee founded in Paris in 1869 by Madame SUDRE, widow of the Inventor.] [This edition from taken from: Copyright © 1997, Stephen L. Rice, Last update: Nov. 19, 1997 URL: http://www2.polarnet.com/~srice/solresol/sorsoeng.htm Edits in [brackets], as well as chapter headings and formatting by Doug Bigham, 2005, for LIN 312.] I. Introduction II. General concepts of solresol III. Words of one [and two] syllable[s] IV. Suppression of synonyms V. Reversed meanings VI. Important note VII. Word groups VIII. Classification of ideas: 1º simple notes IX. Classification of ideas: 2º repeated notes X. Genders XI. Numbers XII. Parts of speech XIII. Number of words XIV. Separation of homonyms XV. Verbs XVI. Subjunctive XVII. Passive verbs XVIII. Reflexive verbs XIX. Impersonal verbs XX. Interrogation and negation XXI. Syntax XXII. Fasi, sifa XXIII. Partitive XXIV. Different kinds of writing XXV. Different ways of communicating XXVI. Brief extract from the dictionary I. Introduction In all the business of life, people must understand one another. But how is it possible to understand foreigners, when there are around three thousand different languages spoken on earth? For everyone's sake, to facilitate travel and international relations, and to promote the progress of beneficial science, a language is needed that is easy, shared by all peoples, and capable of serving as a means of interpretation in all countries. -

![ISSUE 30 | JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 | FREE [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] Alibi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6148/issue-30-july-26-august-1-2018-free-2-weekly-alibi-july-26-august-1-2018-july-26-august-1-2018-weekly-alibi-3-alibi-346148.webp)

ISSUE 30 | JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 | FREE [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] Alibi

OH MY GOD, THAT WAS RAIN SINCE 1992 PHOTO BY ERIC WILLIAMS PHOTOGRAPHY VOLUME 27 | ISSUE 30 | JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 | FREE [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 27 | ISSUE 30 | JULY 26-AUGUST 1, 2018 EDITORIAL MANAGING AND FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC AND NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] ARTS AND LIT.EDITOR: Maggie Grimason (ext. 239) [email protected] FOOD EDITOR: Robin Babb [email protected] COPY EDITOR: Taylor Grabowsky [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR: Ashli Mayo [email protected] STAFF WRITER: Joshua Lee (ext. 243) [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR: Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] EDITORIAL INTERN: Adam Wood [email protected] CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Cecil Adams, Rob Brezsny, Carolyn Carlson, Zabrina Chavez, Desmond Fox, Taylor Grabowsky, Hosho McCreesh, Mayo Lua de Frenchie, Adam Wood PRODUCTION PRODUCTION MANAGER/EDITORIAL DESIGNER: Valerie Serna (ext. 254) [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGNERS: Corey Yazzie [email protected] Ramona Chavez [email protected] STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER: Eric Williams [email protected] CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS: Max Cannon, Michael Ellis, Ryan North, Mike Organisciak, Jen Sorensen SALES SALES DIRECTOR: Tierna Unruh-Enos (ext. 248) [email protected] ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES: Kittie Blackwell (ext. 224) [email protected] John Hankinson (ext. 235) [email protected] Shane Boyd (ext. 223) [email protected] Sarah Shipman (ext. 210) [email protected] STREET TEAM: Alexis Al Omari [email protected] ADMINISTRATION PUBLISHER: Constance Moss (ext. 222) [email protected] CONTROLLER: Courtney Foster (ext. 257) [email protected] SYSTEMS MANAGER: Kyle Silfer (ext. -

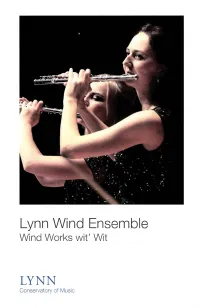

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

A Brief Introduction to Constructed Languages

A Brief Introduction to Constructed Languages An essay by Laurier Rochon Piet Zwart Institute : June 2011 3750 words Abstract The aim of this essay will be to provide a general overview of what is considered a "constructed language" (also called conlang, formalized language or artificial language) and explore some similarities, differences and specific properties that set these languages apart from natural languages. This essay is not meant to be an exhaustive repertoire of all existing conlangs, nor should it be used as reference material to explain or dissect them. Rather, my intent is to explore and distill meaning from particular conlangs subjectively chosen for their proximity to my personal research practice based on empirical findings I could infer from their observation and brief use. I will not tackle the task of interpreting the various qualities and discrepancies of conlangs within this short study, as it would surely consist of an endeavour of its own. It should also be noted that the varying quality of documentation available for conlangs makes it difficult to find either peer-reviewed works or independent writings on these subjects. As a quick example, many artistic languages are conceived and solely used by the author himself/herself. This person is obviously the only one able to make sense of it. This short study will not focus on artlangs, but one would understand the challenge in analyzing such a creation: straying away from the beaten path affords an interesting quality to the work, but also renders difficult a precise analytical study of it. In many ways, I have realized that people involved in constructing languages are generally engaging in a fringe activity which typically does not gather much attention - understandably so, given the supremacy of natural languages in our world. -

Hildegard Transfigured – Programme Copy 2021(1)

Hildegard Transfigured: a medieval trance for the 21st century Hildegard Transfigured is a collaborative piece of concert-theatre by vocal trio Voice, visual artist Innerstrings, and composer Laura Moody that celebrates St. Hildegard of Bingen through song, psychedelic lights, and live visuals. The performance at SJE includes the world premiere of Moody’s Hildegard Portraits. St Hildegard of Bingen (1098 - 1179) joined the monastery in Disibodenberg (in German Rhineland) when she was just eight years old and would stay there for nearly forty years, eventually becoming abbess in 1136. She founded her own abbey at Rupertsberg near Bingen in 1147 and a second monastery in nearby Eibingen in 1165. Throughout her life, Hildegard was a great spiritual leader, theologian, mystic, scientist, and composer. Revered as a saint for centuries, Pope Benedict XVI canonised Hildegard of Bingen on 10 May 2012. Hildegard experienced intense visions, recorded in her major work Scivias (Know the Way), (1141-51), and it is this aspect of her life that the collaboration with visual artist, Innerstrings, will bring to life in Hildegard Transfigured, transfiguring her beautiful music into a new sensory experience. Laura Moody’s research for the show brought her to The Personal Correspondence of Hildegard of Bingen, translated by Joseph L Baird and Radd K Ehrman (OUP 2006). She has set extracts and fragments of Hildegard’s letters in her composition Hildegard Portraits, written especially for this programme. You will hear Moody's music interspersed throughout in the form of miniatures, culminating in the finale The Living Light. “It is some kind of miracle to have the kind of access to a female creator of the twelfth century that we have with Hildegard, her output only having been permissible during her lifetime because of her sacred status. -

![Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[S]: Clare O’Dowd Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6290/kurt-schwitterss-merzbau-chaos-compulsion-and-creativity-author-s-clare-o-dowd-source-moveabletype-vol-696290.webp)

Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[S]: Clare O’Dowd Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Article: Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[s]: Clare O’Dowd Source: MoveableType, Vol. 5, ‘Mess’ (2009) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.046 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2009 Clare O’Dowd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Moveable Type Vol. 5 2009: CLARE O’DOWD 1 Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau : Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity For nearly thirty years until his death in 1948, the German artist Kurt Schwitters constructed environments for himself: self-contained worlds, places of safety, nests. Everywhere he went he stockpiled materials and built them into three-dimensional, sculptural edifices. By the time he left Hanover in 1937, heading for exile in England, Schwitters, his wife, his son, his parents, their lodgers, and a large number of guinea pigs had all been living in the midst of an enormous, detritus-filled sculpture that had slowly engulfed large parts of their home for almost twenty years. 1 Schwitters was by no means the only artist to have a cluttered studio, or to collect materials for his work. So the question must be asked, what was it about Schwitters’ activities that was so unusual? How can these and other aspects of his work and behaviour be considered to go beyond what might be regarded as normal for an artist working at that time? And more importantly, what were the reasons for this behaviour? In this paper, I will examine the beginnings of the Merzbau , the architectural sculpture that Schwitters created in his Hanover home. -

Latinidaj Planlingvoj (AIS-Kurso, 1 Studunuo)

Vĕra Barandovská-Frank: Latinidaj planlingvoj (AIS-kurso, 1 studunuo) La Latina apartenas al la italika grupo de la hindeŭropa lingvofamilio (tiu ĉi lingvofamilio ampleksas i.a. preskaŭ ĉiujn eŭropajn lingvojn, ekz. grupon ĝermanan kaj slavan), el la Latina evoluiĝis etnaj lingvoj nomataj Romanaj ( = latinidaj), precipe itala, romanĉa, sarda, franca, okcitana, hispana, kataluna, galega, portugala, gudezma, rumana, moldava. Latinidaj planlingvoj estas similaj al la Romanaj lingvoj kaj ofte imitas ilian evoluon. Latina skribo (el la greka kaj etruska alfabetoj): originale 20 majusklaj literoj (maiuscula): A B C D E F H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X . Literon I oni uzis ankaŭ por la sono [j], literon C ankaŭ por G, poste diferenciĝis [k] kaj [g]. U kaj V estis la sama litero: majuskle ekzistis nur V, poste minuskle (minuscula) u: VENIO – uenio (minuskloj evoluiĝis el la mezepoka karolinga alfabeto). En la klasika latina ne estis K, k, J j, U, u, v, W, w, Y, y, Z, z poste trans- prenitaj aŭ el la greka alfabeto (K, U, Y, Z ), aŭ faritaj el jam ekzistantaj literoj (J, W). Restaŭrita prononco: vokaloj longaj kaj mallongaj. La litero V/u estas aŭ konsonanta [ŭ] aŭ vokala [u]; i (j) aŭ konsonanta [j] aŭ vokala [i]. La litero c prononciĝis kiel [k]; qu kiel [kŭ]; au kiel [aŭ]; ae kiel [aj]; oe kiel [oj]. h estis antikve ĉiam prononcata, sed iom post iom malaperis. En helenaj pruntvortoj estis uzataj ch, ph, th [kh]/[ĥ], [ph], [th], poste [k], [p], [t]. La akcento ĝenerale troviĝis sur la antaŭlasta silabo, se ĝia vokalo estis longa, aŭ je la antaŭantaŭlasta, se mallonga, ekz. -

Nf the Search Album Download Nf the Search Album Download

nf the search album download Nf the search album download. 1) Select a file to send by clicking the "Browse" button. You can then select photos, audio, video, documents or anything else you want to send. The maximum file size is 500 MB. 2) Click the "Start Upload" button to start uploading the file. You will see the progress of the file transfer. Please don't close your browser window while uploading or it will cancel the upload. 3) After a succesfull upload you'll receive a unique link to the download site, which you can place anywhere: on your homepage, blog, forum or send it via IM or e-mail to your friends. NF “The Search Album” Full review and album Rating! ( Eminem vs NF, NF #1 Rap Album ) We hope if you download NF “The Search Album” Full review and album Rating! ( Eminem vs NF, NF #1 Rap Album ) just for the review purpose only. and then if you like the song NF “The Search Album” Full review and album Rating! ( Eminem vs NF, NF #1 Rap Album ) don't forget to buy the orginal one to support the singers. you also can download NF “The Search Album” Full review and album Rating! ( Eminem vs NF, NF #1 Rap Album ) for legal on Apple Music or iTunes officiall music artist. NF – The Search. “The Search” is the first single and title track for NF ’s fourth album and marks his first release of 2019. On the track, NF opens up about the struggles inside his head and dealing with fame. -

Dissertation Body

Summary of Three Dissertation Recitals by Leo R. Singer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Aaron, Chair Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Joseph Gascho Professor Andrew Jennings Professor James Joyce Leo R. Singer [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2741-1104 © Leo R. Singer 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was made possible by the incredible faculty at the University of Michigan. Each course presented new information and ways of thinking, which in turn inspired the programming and performing choices for these three dissertation recitals. I would like to thank all the collaborators who worked tirelessly to make these performances special. I also must express my sincere and utmost gratitude to Professor Richard Aaron for his years of guidance, mentorship and inspiration. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, Scott and Rochelle, my sister, Julie, the rest of my family, and all of my friends for their unwavering support throughout the many ups and downs during my years of education. !ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv RECITALS I. MUSIC FROM FRANCE 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM NOTES 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 II. MUSIC FROM GERMANY AND AUSTRIA 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM NOTES 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 III. MUSIC FROM AMERICA 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM NOTES 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 !iii ABSTRACT In each of the three dissertation cello recitals, music from a different nation is featured. The first is music from France, the second from Germany and Austria, and the third from America.