Choral Music of Ernst Toch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

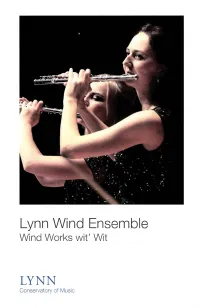

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

Dissertation Body

Summary of Three Dissertation Recitals by Leo R. Singer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Aaron, Chair Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Joseph Gascho Professor Andrew Jennings Professor James Joyce Leo R. Singer [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2741-1104 © Leo R. Singer 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was made possible by the incredible faculty at the University of Michigan. Each course presented new information and ways of thinking, which in turn inspired the programming and performing choices for these three dissertation recitals. I would like to thank all the collaborators who worked tirelessly to make these performances special. I also must express my sincere and utmost gratitude to Professor Richard Aaron for his years of guidance, mentorship and inspiration. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, Scott and Rochelle, my sister, Julie, the rest of my family, and all of my friends for their unwavering support throughout the many ups and downs during my years of education. !ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv RECITALS I. MUSIC FROM FRANCE 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM NOTES 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 II. MUSIC FROM GERMANY AND AUSTRIA 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM NOTES 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 III. MUSIC FROM AMERICA 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM NOTES 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 !iii ABSTRACT In each of the three dissertation cello recitals, music from a different nation is featured. The first is music from France, the second from Germany and Austria, and the third from America. -

Ernst Toch Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft0z09n428 No online items Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library Special Collections staff and Kendra Wittreich; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 PASC-M 1 1 Title: Ernst Toch papers Collection number: PASC-M 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: German Physical Description: 44.0 linear ft.(88 boxes) Date (inclusive): ca. 1835-1988 Abstract: The Collection consists of materials relating to the Austrian-American composer, Ernst Toch. Included are music manuscripts and scores, books of his personal library, manuscripts, biographical material, correspondence, articles, essays, speeches, lectures, programs, clippings, photographs, sound recordings, financial records, and memorabilia. Also included are manuscripts and published works of other composers, as well as Lilly Toch's letters and lectures. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Toch, Ernst 1887-1964 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

Berg's Worlds

Copyrighted Material Berg’s Worlds CHRISTOPHER HAILEY Vienna is not the product of successive ages but a layered composite of its accumulated pasts. Geography has made this place a natural crossroads, a point of cultural convergence for an array of political, economic, religious, and ethnic tributaries. By the mid-nineteenth century the city’s physical appearance and cultural characteristics, its customs and conventions, its art, architecture, and literature presented a collage of disparate historical elements. Gothic fervor and Renaissance pomp sternly held their ground against flights of rococo whimsy, and the hedonistic theatricality of the Catholic Baroque took the pious folk culture from Austria’s alpine provinces in worldly embrace. Legends of twice-repelled Ottoman invasion, dreams of Holy Roman glories, scars of ravaging pestilence and religious perse- cution, and the echoes of a glittering congress that gave birth to the post-Napoleonic age lingered on amid the smug comforts of Biedermeier domesticity. The city’s medieval walls had given way to a broad, tree-lined boulevard, the Ringstrasse, whose eclectic gallery of historical styles was not so much a product of nineteenth-century historicist fantasy as the styl- ized expression of Vienna’s multiple temporalities. To be sure, the regulation of the Danube in the 1870s had channeled and accelerated its flow and introduced an element of human agency, just as the economic boom of the Gründerzeit had introduced opportunities and perspectives that instilled in Vienna’s citizens a new sense of physical and social mobility. But on the whole, the Vienna that emerged from the nineteenth century lacked the sense of open-ended promise that charac- terized the civic identities of midwestern American cities like Chicago or St. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1965-1966

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 1966 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation I " STMVINSKY tt.VlOW agon vam 7/re Boston Symphony SCHULLER 7 STUDIES ox THEMES of PAUL KLEE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH lEINSDORf under Leinsdorf Leinsdorf expresses with great power the vivid colors of Schuller's Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Kiee and, in the same album, Stravinsky's ballet music from Agon. Forthe majorsinging roles in Menotti's dramatic cantata, The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi. Leinsdorf astutely selected George London, and Lili Chookasian, of whom the Chicago Daily Tribune has written, "Her voice has the Boston symphony ecich teinsooof / luminous tonal sheath that makes listening luxurious. menotti Also hear Chookasian in this same album, in songs from the death op the Bishop op BRSndlSI Schbnberg's Gurre-Lieder. In Dynagroove sound. Qeonoe ionoon • tilt choolusun s<:b6notec,/ou*«*--l(eoeo. sooq of the wooo-6ove ac^acm rca Victor fa @ The most trusted name in sound ^V V BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH LeinsDORF, Director Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus Louis Speyer, Assistant Director Victor Babin, Chairman of the Tanglewood Institute Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM Contemporary Music Activities Gunther Schuller, Head Roger Sessions, George Rochberg, and Donald Martino, Guest Teachers Paul Zukofsky, Fromm Teaching Fellow James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Viola C Aliferis, Assistant Administrator The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. -

AMERICAN CLASSICS Ernst TOCH Piano Quintet Three Impromptus • Violin Sonata No

559324 bk Toch US 2/15/08 12:30 PM Page 8 Also available: AMERICAN CLASSICS Ernst TOCH Piano Quintet Three Impromptus • Violin Sonata No. 2 • Burlesken Spectrum Concerts Berlin 8.559199 8.559282 8.559324 8 559324 bk Toch US 2/15/08 12:30 PM Page 2 Ernst Toch (1887-1964) Frank Dodge Chamber Music Frank Dodge was born in Boston in 1950 and began studying the cello at the age of sixteen. His instructors were Somehow the boy procured miniature scores of Jacobus Langendoen, Aldo Parisot, Pierre Fournier, Eberhard Finke and Maurice Gendron. He attended master- several Mozart string quartets, and, lining his own classes of Janos Starker and Mstislav Rostropovich. He received a BM from the New England Conservatory and a paper—it would still be several years before he learned MM from Yale University. He founded the Strawbery Banke Chamber Music Festival, Inc. in Portsmouth, New of the existence of music paper—he began to copy them Hampshire and was artistic director and cellist from 1969 to 1980. Frank Dodge was a founding member of the out under his bed covers at night, thereby intuitively Portsmouth Chamber Ensemble, winners in 1981 of the Artists International Competition in New York and frequent discerning the structure of the individual movements. guests on series such as the Cleveland Museum of Art at University Circle, the Harvard Musical Association, One night he thus copied out Mozart, but only up to the Carnegie Recital Hall, Bay Chamber Concerts and the Machais Bay Chamber Concerts. He lived in New York from repeat sign, thereafter improvising his own 1978 to 1982 as member of the Opera Orchestra of New York, the St Lukes Chamber Ensemble, and the Orchestra development: “Then I compared with the original,” he of Our Time, and as principal cellist of the Stanford Symphony. -

New Approaches to Melody in 1920S Musical Thought

Sounding Lines: New Approaches to Melody in 1920s Musical Thought The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Probst, Stephanie. 2018. Sounding Lines: New Approaches to Melody in 1920s Musical Thought. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41127157 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 2018, Stephanie Probst All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Suzannah Clark Stephanie Probst Sounding Lines: New Approaches to Melody in 1920s Musical Thought Abstract This dissertation identifies a new concept of melody that emerged in early twentieth- century Germany at the intersection of developments in composition, music theory, philosophy, the visual arts, and psychology. Focusing on the widespread analogy of the line, which came to encapsulate melody as an autonomous, temporally evolving yet coherently perceived musical entity, the study investigates how theorists unleashed melody from the hegemony of nineteenth- century harmony and theorized its structuring principles independently from vertical ties. Recent theories of visualization frame readings of an interdisciplinary body of sources to illuminate the ways in which the melodic line bridged physical and psychological models of music, temporal and spatial perspectives, and theories of visual and aural cognition. The first two chapters chronicle the revival and re-conceptualization of the line in the visual arts and of melody in music around 1900 as parallel developments. -

A Foundational Approach to Core Music Instruction in Undergraduate Music Theory Based on Common Universal Principles

A FOUNDATIONAL APPROACH TO CORE MUSIC INSTRUCTION IN UNDERGRADUATE MUSIC THEORY BASED ON COMMON UNIVERSAL PRINCIPLES Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christy Jo Talbott, B.A., B.S., M.M. The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Gregory M. Proctor, Ph.D., Advisor Approved by Burdette Green, Ph.D. Daniel Avorgbedor, Ph.D. __________________________ Advisor Music Graduate Program Copyright by Christy Jo Talbott 2008 ABSTRACT Music is a large subject with many diverse subcategories (Pop, Classical, Reggae, Jazz, and so on). Each subcategory, classified as a genre for its unique qualities, should relate in some way to that broader subject. These unique properties, however, do not negate all possible relationships among the genres. That these subcategories fit under a “music” label implies that they contain commonalities that transcend their differences. If there is, then, a set of commonalities for this abstract concept of music, then an examination of musics from diverse cultures should illuminate this fact. This “set of commonalities” for a real subject called music should not be limited to the Germanic tradition of the 16th-18th century or to Parisian art song of the 19th but, instead, is open to a world repertoire unbounded by era or nation. Every culture has invented a music of its own. The task here is to show that, from a variety of sources, a basic set of elements is common across cultures. In addition, those elements do not distinguish one category from another but, instead, collectively suggest a set of common principles. -

A Wind Ensemble Adaptation and Conductor's Analysis of Selected Movements of Darius Milhaud's Saudades Do Brazil, with A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2005 A wind ensemble adaptation and conductor's analysis of selected movements of Darius Milhaud's Saudades do Brazil, with an examination of the influences of Ernesto Nazareth Monty Roy Musgrave Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Musgrave, Monty Roy, "A wind ensemble adaptation and conductor's analysis of selected movements of Darius Milhaud's Saudades do Brazil, with an examination of the influences of Ernesto Nazareth" (2005). LSU Major Papers. 32. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/32 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A WIND ENSEMBLE ADAPTATION AND CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS OF SELECTED MOVEMENTS OF DARIUS MILHAUD’S SAUDADES DO BRAZIL, WITH AN EXAMINATION OF THE INFLUENCES OF ERNESTO NAZARETH A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Monty Roy Musgrave B.M.E., University of Florida, 1982 M.M., Florida State University, 1994 August 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the members of my committee, including my Major Professor, Frank B. Wickes, for supporting the ideas that resulted in the culmination of this project.