New Approaches to Melody in 1920S Musical Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Music of Ernst Toch

THE CHORAL MUSIC OF ERNST TOCH By MIRIAM SUSAN ZACH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTL^L FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1993 Copyright 1993 by Miriam Susan Zach ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to Mikesch Miicke, life-partner and architect, for his patience, encouragement, and introduction to Venturi's thought. His ability to clarify mysteries of computers and the German language made this dissertation a reaUty. She would like to express her deepest gratitude to her parents, Margaret Munster Zach and Herbert William Zach, for a lifetime of support and for advocating the research, teaching, and performance of music. She feels fortunate to have had the opportunity to study music history and Uterature wdth Dr. David Z. Kushner, a master teacher, pianist, and researcher, a mentor who cares. The author is grateful to Dr. Otto W. Johnston for his persistence to help her develop a cogent argument, for responding promptly with thoughtful insights that focused fragmentary ideas, and his humor during the long process. She would also like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Budd Udell, Dr. Arthur Jennings, Dr. PhyUis Dorman, Dr. Russell Robinson, and Professor Reid Poole for their counsel and collective effort to teach her how to fish. She would like to honor Dr. Robert and MilUe Ramey for their encouraging presence and thoughtfulness. Marsha Berman and Stephen Fry at the UCLA Toch Archive gave their time and expertise during the author's two visits to the collection, and made long-distance research possible. -

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and Their Use for Composition

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and their Use for Composition submitted by Georg Boenn for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Bath Department of Computer Science February 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author. This thesis may not be consulted, photocopied or lent to other libraries without the permission of the author for 3 years from the date of acceptance of the thesis. Signature of Author . .................................. Georg Boenn To Daiva, the love of my life. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Musical Time and the Problem of Musical Form . 17 1.2 Context of Research and Research Questions . 18 1.3 Previous Publications . 24 1.4 Contributions..................................... 25 1.5 Outline of the Thesis . 27 2 Background and Related Work 28 2.1 Introduction...................................... 28 2.2 Representations of Musical Rhythm . 29 2.2.1 Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 29 2.2.2 The Piano-Roll Notation . 33 2.2.3 Necklace Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 34 2.2.4 Adjacent Interval Spectrum . 36 2.3 Onset Detection . 36 2.3.1 ManualTapping ............................... 36 The times Opcode in Csound . 38 2.3.2 MIDI ..................................... 38 MIDIFiles .................................. 38 MIDIinReal-Time.............................. 40 2.3.3 Onset Data extracted from Audio Signals . 40 2.3.4 Is it sufficient just to know about the onset times? . 41 2.4 Temporal Perception . -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - - NEW YORK Twenty-second Season in New York DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fnigrammra of % FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THK FIRST MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 9 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH COMPANY . 37 West 32d Street, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Czerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. < Second Violins. • Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Ferir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. t Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loefner, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. -

Vezzosi A. Sabato A. the New Genealogical Tree of the Da Vinci

HUMAN EVOLUTION Vol. 36 - n. 1-2 (1-90) - 2021 Vezzosi A. The New Genealogical Tree of the Da Vinci Leonardo scholar, art historian Family for Leonardo’s DNA. Founder of Museo Ideale Leonardo Da Vinci Ancestors and descendants in direct male Via IV Novembre 2 line down to the present XXI generation* 50059 Vinci (FI), Italy This research demonstrates in a documented manner the con- E-mail: [email protected] tinuity in the direct male line, from father to son, of the Da Vinci family starting with Michele (XIV century) to fourteen Sabato A. living descendants through twenty-one generations and four Historian, writer different branches, which from the XV generation (Tommaso), President of Associazione in turn generate other line branches. Such results are eagerly Leonardo Da Vinci Heritage awaited from an historical viewpoint, with the correction of the E-mail: leonardodavinciheritage@ previous Da Vinci trees (especially Uzielli, 1872, and Smiraglia gmail.com Scognamiglio, 1900) which reached down to and hinted at the XVI generation (with several errors and omissions), and an up- DOI: 10.14673/HE2021121077 date on the living. Like the surname, male heredity connects the history of regis- try records with biological history along separate lineages. Be- KEY WORDS: Leonardo Da Vinci, cause of this, the present genealogy, which spans almost seven Da Vinci new genealogy, ancestors, hundred years, can be used to verify, by means of the most living descendants, XXI generations, innovative technologies of molecular biology, the unbroken Domenico di ser Piero, Y chromosome, transmission of the Y chromosome (through the living descend- Florence, Bottinaccio (Montespertoli), ants and ancient tombs, even if with some small variations due burials, Da Vinci family tomb in Vinci, to time) with a view to confirming the recovery of Leonardo’s Santa Croce church in Vinci, Ground Y marker. -

LEONARDO, POLITICS and ALLEGORIES Marco Versiero

LEONARDO, POLITICS AND ALLEGORIES Marco Versiero To cite this version: Marco Versiero. LEONARDO, POLITICS AND ALLEGORIES. De Agostini. 2010, Codex Atlanticus, 978-88-418-6391-6. halshs-01385250 HAL Id: halshs-01385250 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01385250 Submitted on 21 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Catalogo_Leonardo_04B@1000-1003 24-05-2010 11:45 Pagina 1 04 L’esposizione dei fogli del Codice Atlantico, The exhibition of folios from the Codex LEONARDO, LA POLITICA E LE ALLEGORIE l’incredibile raccolta di disegni Atlanticus, Leonardo da Vinci’s amazing LEONARDO, LA POLITICA di Leonardo da Vinci, vuole mettere collection of drawings, offers the public a disposizione del pubblico uno spaccato an authentic insight into the genius 04 E LE ALLEGORIE del genio del Maestro che, meglio of the great master. It was he, more than any DISEGNI DI LEONARDO DAL CODICE ATLANTICO di ogni altro, seppe intuire la connessione other, who perceived the interconnections fra le forze della natura e i benefici between the forces of nature and the benefits LEONARDO, POLITICS AND ALLEGORIES che l’umanità avrebbe potuto trarne. -

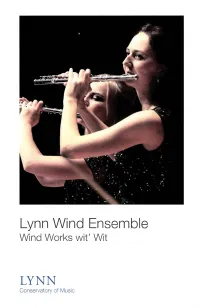

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

Leonardo and the Whale

Biology Faculty Publications Biology 6-17-2019 Leonardo and the Whale Kay Etheridge Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/biofac Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Etheridge, Kay. "Leonardo and the Whale." In Leonardo da Vinci – Nature and Architecture, edited by C. Moffat and S.Taglialagamba, 89-106. Leiden: Brill, 2019. This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/biofac/81 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leonardo and the Whale Abstract Around 1480, when he was 28 years old, Leonardo da Vinci recorded what may have been a seminal event in his life. In writing of his travels to view nature he recounted an experience in a cave in the Tuscan countryside: Having wandered for some distance among overhanging rocks, I can to the entrance of a great cavern... [and after some hesitation I entered] drawn by a desire to see whether there might be any marvelous thing within..." [excerpt] Keywords Leonardo da Vinci, fossils, whale Disciplines Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture | Biology | Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Marine Biology Comments Please note that that this is pre-print version of the article and has not yet been peer-reviewed. -

Newsletter Nov 2015

Leonardo da Vinci Society Newsletter Editor: Matthew Landrus Issue 42, November 2015 Recent and forthcoming events did this affect the science of anatomy? This talk discusses the work of Leonardo da Vinci, The Annual General Meeting and Annual Vesalius and Fabricius and looks at how the Lecture 2016 nature of the new art inspired and shaped a new wave of research into the structure of the Professor Andrew Gregory (University College, human body and how such knowledge was London), will offer the Annual Lecture on Friday, transmitted in visual form. This ultimately 13 May at 6 pm. The lecture, entitled, ‘Art and led to a revolution in our under-standing of Anatomy in the 15th & 16th Centuries’ will be anatomy in the late 16th and early 17th centu- at the Kenneth Clark Lecture Theatre of the ries. Courtauld Institute of Art (Somerset House, The Strand). Before the lecture, at 5:30 pm, the annual Lectures and Conference Proceedings general meeting will address matters arising with the Society. Leonardo in Britain: Collections and Reception Venue: Birkbeck College, The National Gallery, The Warburg Institute, London Date: 25-27 May 2016 Organisers: Juliana Barone (Birkbeck, London) and Susanna Avery-Quash (National Gallery) Tickets: Available via the National Gallery’s website: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/whats- on/calendar/leonardo-in-britain-collections-and- reception With a focus on the reception of Leonardo in Britain, this conference will explore the important role and impact of Leonardo’s paintings and drawings in key British private and public collec- tions; and also look at the broader British context of the reception of his art and science by address- ing selected manuscripts and the first English editions of his Treatise on Painting, as well as historiographical approaches to Leonardo. -

Dissertation Body

Summary of Three Dissertation Recitals by Leo R. Singer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Aaron, Chair Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Joseph Gascho Professor Andrew Jennings Professor James Joyce Leo R. Singer [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2741-1104 © Leo R. Singer 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was made possible by the incredible faculty at the University of Michigan. Each course presented new information and ways of thinking, which in turn inspired the programming and performing choices for these three dissertation recitals. I would like to thank all the collaborators who worked tirelessly to make these performances special. I also must express my sincere and utmost gratitude to Professor Richard Aaron for his years of guidance, mentorship and inspiration. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, Scott and Rochelle, my sister, Julie, the rest of my family, and all of my friends for their unwavering support throughout the many ups and downs during my years of education. !ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv RECITALS I. MUSIC FROM FRANCE 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM NOTES 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 II. MUSIC FROM GERMANY AND AUSTRIA 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM NOTES 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 III. MUSIC FROM AMERICA 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM NOTES 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 !iii ABSTRACT In each of the three dissertation cello recitals, music from a different nation is featured. The first is music from France, the second from Germany and Austria, and the third from America. -

Music in the 20Th Century Serialism Background Information to Five Orchestral Pieces

AOS 2: Music in the 20th Century Serialism Background Information to Five Orchestral Pieces Five Orchestral Pieces 1909 by Arnold Schoenberg is a set of atonal pieces for full orchestra. Each piece lasts between one to five minutes and they are not connected to one another by the use of any musical material. Richard Strauss requested that Schoenberg send him some short orchestral pieces with the possibility of them gaining some attention from important musical figures. Schoenberg hadn’t written any orchestral pieces since 1903 as he had been experimenting with and developing his ideas of atonality in small scale works. He had had a series of disappointments as some of his works for both chamber orchestra and larger ensembles had been dismissed by important musical figures as they did not understand his music. As a result of this Schoenberg withdrew further into the small group of like minded composers e.g. The Second Viennese School. Schoenberg uses pitches and harmonies for effect not because they are related to one another. He is very concerned with the combinations of different instrumental timbres rather than melody and harmony as we understand and use it. Schoenberg enjoyed concealing things in his music; he believed that the intelligent and attentive listener would be able to decipher the deeper meanings. Schoenberg believed that music could express so much more than words and that words detract from the music. As a result of this belief titles for the Five Orchestral Pieces did not appear on the scores until 13 years after they had been composed. -

Ernst Toch Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft0z09n428 No online items Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library Special Collections staff and Kendra Wittreich; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 PASC-M 1 1 Title: Ernst Toch papers Collection number: PASC-M 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: German Physical Description: 44.0 linear ft.(88 boxes) Date (inclusive): ca. 1835-1988 Abstract: The Collection consists of materials relating to the Austrian-American composer, Ernst Toch. Included are music manuscripts and scores, books of his personal library, manuscripts, biographical material, correspondence, articles, essays, speeches, lectures, programs, clippings, photographs, sound recordings, financial records, and memorabilia. Also included are manuscripts and published works of other composers, as well as Lilly Toch's letters and lectures. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Toch, Ernst 1887-1964 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Alban Berg's Filmic Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn, "Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ALBAN BERG’S FILMIC MUSIC: INTENTIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF THE FILM MUSIC INTERLUDE IN THE OPERA LULU A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith A.B., Smith College, 1993 A.M., Smith College, 1995 M.L.I.S., Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1999 May 2002 ©Copyright 2002 Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to express gratitude to my wonderful committee for working so well together and for their suggestions and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Jan Herlinger, my dissertation advisor, for his insightful guidance, care and precision in editing my written prose and translations, and open mindedness.