INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Music of Ernst Toch

THE CHORAL MUSIC OF ERNST TOCH By MIRIAM SUSAN ZACH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTL^L FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1993 Copyright 1993 by Miriam Susan Zach ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to Mikesch Miicke, life-partner and architect, for his patience, encouragement, and introduction to Venturi's thought. His ability to clarify mysteries of computers and the German language made this dissertation a reaUty. She would like to express her deepest gratitude to her parents, Margaret Munster Zach and Herbert William Zach, for a lifetime of support and for advocating the research, teaching, and performance of music. She feels fortunate to have had the opportunity to study music history and Uterature wdth Dr. David Z. Kushner, a master teacher, pianist, and researcher, a mentor who cares. The author is grateful to Dr. Otto W. Johnston for his persistence to help her develop a cogent argument, for responding promptly with thoughtful insights that focused fragmentary ideas, and his humor during the long process. She would also like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Budd Udell, Dr. Arthur Jennings, Dr. PhyUis Dorman, Dr. Russell Robinson, and Professor Reid Poole for their counsel and collective effort to teach her how to fish. She would like to honor Dr. Robert and MilUe Ramey for their encouraging presence and thoughtfulness. Marsha Berman and Stephen Fry at the UCLA Toch Archive gave their time and expertise during the author's two visits to the collection, and made long-distance research possible. -

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

HINDEMITH VAN DER ROOST Clarinet Concertos Eddy Vanoosthuyse, Clarinet Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra Sergio Rosales, Conductor

HINDEMITH VAN DER ROOST Clarinet Concertos Eddy Vanoosthuyse, Clarinet Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra Sergio Rosales, Conductor 1 Paul Hindemith (1895−1963): Clarinet Concerto Born in Frankfurt in 1895, the son of a house-painter, Paul Hindemith studied the violin privately with teachers from the Hoch Conservatory before being admitted to that institution with a free place at the age of thirteen. By 1915 he was playing second violin in his teacher Adolf Rebner’s quartet and had a place in the opera orchestra, of which he became leader in the same year. His father was killed in the war and Hindemith himself spent some time from 1917 as a member of a regimental band, returning after the war to the Rebner Quartet and the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. At the same time he was making his name as a composer of particular originality, striving to bring about a revolution in concert-going with his concept of Gebrauchsmusik (functional or utility music), and devoting much of his energy to the promotion of new music, in particular at the Donaueschingen Festival. Having changed from violin to viola, he formed the Amar-Hindemith Quartet in 1921, an ensemble that won considerable distinction for its performances of new music. In 1927 Hindemith was appointed professor of composition at the Berlin Musikhochschule, two years later disbanding the quartet – to which he could no longer give time – and instead performing in a string trio with Josef Wolfsthal, (replaced on his death by Szymon Goldberg) and the cellist Emanuel Feuermann. He was also enjoying a career as a viola soloist. -

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

El Lissitzky Letters and Photographs, 1911-1941

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6r29n84d No online items Finding aid for the El Lissitzky letters and photographs, 1911-1941 Finding aid prepared by Carl Wuellner. Finding aid for the El Lissitzky 950076 1 letters and photographs, 1911-1941 ... Descriptive Summary Title: El Lissitzky letters and photographs Date (inclusive): 1911-1941 Number: 950076 Creator/Collector: Lissitzky, El, 1890-1941 Physical Description: 1.0 linear feet(3 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The El Lissitzky letters and photographs collection consists of 106 letters sent, most by Lissitzky to his wife, Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, along with his personal notes on art and aesthetics, a few official and personal documents, and approximately 165 documentary photographs and printed reproductions of his art and architectural designs, and in particular, his exhibition designs. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in German Biographical/Historial Note El Lissitzky (1890-1941) began his artistic education in 1909, when he traveled to Germany to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule in Darmstadt. Lissitzky returned to Russia in 1914, continuing his studies in Moscow where he attended the Riga Polytechnical Institute. After the Revolution, Lissitzky became very active in Jewish cultural activities, creating a series of inventive illustrations for books with Jewish themes. These formed some of his earliest experiments in typography, a key area of artistic activity that would occupy him for the remainder of his life. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

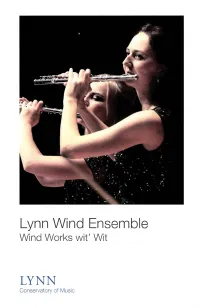

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /.