Dissertation Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Music of Ernst Toch

THE CHORAL MUSIC OF ERNST TOCH By MIRIAM SUSAN ZACH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTL^L FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1993 Copyright 1993 by Miriam Susan Zach ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to Mikesch Miicke, life-partner and architect, for his patience, encouragement, and introduction to Venturi's thought. His ability to clarify mysteries of computers and the German language made this dissertation a reaUty. She would like to express her deepest gratitude to her parents, Margaret Munster Zach and Herbert William Zach, for a lifetime of support and for advocating the research, teaching, and performance of music. She feels fortunate to have had the opportunity to study music history and Uterature wdth Dr. David Z. Kushner, a master teacher, pianist, and researcher, a mentor who cares. The author is grateful to Dr. Otto W. Johnston for his persistence to help her develop a cogent argument, for responding promptly with thoughtful insights that focused fragmentary ideas, and his humor during the long process. She would also like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Budd Udell, Dr. Arthur Jennings, Dr. PhyUis Dorman, Dr. Russell Robinson, and Professor Reid Poole for their counsel and collective effort to teach her how to fish. She would like to honor Dr. Robert and MilUe Ramey for their encouraging presence and thoughtfulness. Marsha Berman and Stephen Fry at the UCLA Toch Archive gave their time and expertise during the author's two visits to the collection, and made long-distance research possible. -

Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: the Success of Arthur Honeggerâ•Žs Antigone in Vichy France

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 7 2021 Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France Emma K. Schubart University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Schubart, Emma K. (2021) "Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 7 MUSICAL HYBRIDIZATION AND POLITICAL CONTRADICTION: THE SUCCESS OF ARTHUR HONEGGER’S ANTIGONE IN VICHY FRANCE EMMA K. SCHUBART, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL MENTOR: SHARON JAMES Abstract Arthur Honegger’s modernist opera Antigone appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1943, sixteen years after its unremarkable premiere in Brussels. The sudden Parisian success of the opera was extraordinary: the work was enthusiastically received by the French public, the Vichy collaborationist authorities, and the occupying Nazi officials. The improbable wartime triumph of Antigone can be explained by a unique confluence of compositional, political, and cultural realities. Honegger’s compositional hybridization of French and German musical traditions, as well as his opportunistic commercial motivations as a Swiss composer working in German-occupied France, certainly aided the success of the opera. -

Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Four • Persons Auditorium Saturday, August 3 at 8:00pm Sieben frühe Lieder (1905-08) Dolce Cantavi (2015) Alban Berg Caroline Shaw Born February 9, 1885 Born August 1, 1982 Died December 24, 1935 Duration: approx. 3 minutes Duration: approx. 15 minutes Marlboro premiere Last Marlboro performance: 1997 Berg’s Sieben frühe Liede, literally “seven early songs,” As she has done in other works such as her piano were written while he was still a student of Arnold concerto for Jonathan Biss, which was inspired by Schoenberg. In fact, three of these songs were premiered Beethoven’s third piano concerto, Shaw looks into music in a concert by Schoenberg’s students in late 1907, history to compose music for the present. This piece in around the time that Berg met the woman whom he particular eschews fixed meter to recall the conventions would marry. In honor of the 10-year anniversary of this of early music and to highlight the natural rhythms of the meeting, he later revisited and corrected a final version of libretto. The text of this short but wonderfully involved the songs. The whole set was not published until 1928, song is taken from a poem by Francesca Turini Bufalini when Berg arranged an orchestrated version. Each song (1553-1641). Not only does the language harken back to features text by a different poet, so there is no through- an artistic period before our own, but the music flits narrative, however the songs all feature similar themes, through references of erstwhile luminaries such as revolving around night, longing, and infatuation. -

Submitted to the Faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2015

A HANDBOOK FOR INTRODUCING UNDERGRADUATES TO THE ORGAN AND ITS LITERATURE BY PATRICK EUGENE POPE Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Katherine Strand, Research Director __________________________________ Christopher Young, Chairperson __________________________________ Mary Ann Hart __________________________________ Marilyn Keiser September 17, 2015 ii Copyright © 2015 Patrick E. Pope iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to acknowledge his organ teachers and professors, whose instruction led to a discerned need for this handbook and its creation: Donnie Beddingfield (1994-1998); William Bates (1998-2002); Marilyn Keiser (2002-2004); Todd Wilson (2008- 2009); and Christopher Young (2009-present). Their love and passion for teaching, performing, and researching has kindled the writer’s interest in the organ, its music, and its literature. The writer is a better musician because of their wisdom and encouragement. The writer wishes to thank the Reverend Kevin Brown, rector, and the parish of Holy Comforter Episcopal Church, Charlotte, North Carolina for their encouragement during the final stages of the doctoral degree. The writer wishes to thank the members of his doctoral research committee and other faculty for their guidance and professional support: Katherine Strand, research director; Christopher Young, chairperson; Janette Fishell; Marilyn Keiser; Mary Ann Hart; and Bruce Neswick. In particular, the writer is grateful to Professor Young for his insightful and energizing classroom teaching in a four-semester organ literature survey at Indiana University, in which the writer was privileged to take part during master’s and doctoral coursework. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

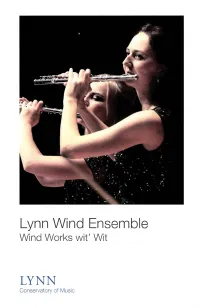

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

Sophocles' Antigone Reworked in the Twentieth

NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Issue 12 (2018) SOPHOCLES’ ANTIGONE REWORKED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE CASE OF HASENCLEVER’S ANTIGONE (1917) © Rossana Zetti (University of Edinburgh) INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXTUALIZATION This article examines a little-known example of Antigone’s reception in the twentieth century: the adaptation by the German expressionist writer Walter Hasenclever. This version is the first and arguably most innovative of several European adaptations of Sophocles’ play to appear in the first half of the twentieth century. Although successful at the time of its production, Hasenclever’s Antigone is scarcely read in contemporary scholarship and is discussed mainly in German-language scholarship.1 Whereas Flashar’s wide-ranging study, in German, refers to Hasenclever’s drama (Flashar 2009: 127– 29), in Fischer-Lichte’s 2017 book Tragedy’s Endurance, in English, Hasenclever appears only in one endnote (Fischer-Lichte 2017: 143). The only English translation of the play available (Ritchie and Stowell 1969: 113–60) is rather out of date and inaccessible. Hasenclever’s Antigone is briefly mentioned in Steiner’s essential reference book Antigones (Steiner 1984: 142; 146; 170; 218), in the chapter on Antigone in the recent Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Sophocles (Silva 2017: 406–7) and in Cairns’ 2016 book on Sophocles’ Antigone (Cairns 2016: 133). However, it is absent in some of the most recent contributions dedicated to the play’s modern reception, including Wilmer’s and Žukauskaitė’s edited collection on Antigone in postmodern thought (2010), Mee’s and Foley’s essays (2011) discussing adaptations of Antigone staged around the world, and Morais’, Hardwick’s and Silva’s recent volume (2017).2 The absence of Hasenclever from contemporary scholarship can be explained by the fact that his Antigone lacks the complexity of later adaptations, such as Anouilh’s and Brecht’s. -

Bärenreiter Organ Music

>|NAJNAEPAN KNC=JIQOE? .,-.+.,-/ 1 CONTENTS Organ Music Solo Voice and Organ ...............30 Index by Collections and Series ...........4–13 Books............................................... 31 Edition Numbers ....................... 34 Composers ....................................14 Contemporary Music Index by Jazz .............................................. 29 A Selection ..............................32 Composers / Collections .........35 Transcriptions for Organ .........29 Photo: Edition Paavo Blåfi eld ABBREVIATIONS AND KEY TO FIGURES Ed. Editor Contents Ger German text Review Eng English text Content valid as of May 2012. Bärenreiter-Verlag Fr French text Errors excepted and delivery terms Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG Lat Latin text subject to change without notice. International Department BA Bärenreiter Edition P.O. Box 10 03 29 H Bärenreiter Praha Cover design with a photograph D-34003 Kassel · Germany SM Süddeutscher Musikverlag by Edition Paavo Blåfi eld. Series E-Mail: paavo@blofi eld.de www.baerenreiter.com a.o. and others www.blofi eld.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed in Germany 3/1206/10 · SPA 238 2 Discover Bärenreiter … www.baerenreiter.com Improved Functionality Simple navigation enables quick orientation Clear presentation Improved Search Facility Comprehensive product information User-friendly searches by means of keywords Product recommendations Focus A new area where current themes are presented in detail … the new website3 ORGAN Collections and Series Enjoy the Organ Ave Maria, gratia plena Ave-Maria settings The new series of easily playable pieces for solo voice and organ (Lat) BA 8250 page 30 Enjoy the Organ I contains a collection of stylistically varied Bärenreiter Organ Albums pieces for amateur organists Collections of organ pieces which are equally suitable for page 6-7 use in church services and in concerts. -

Pacific 231 (Symphonic Movement No

Pacific 231 (Symphonic Movement No. 1) Arthur Honegger (1892–1955) Written: 1923 Movements: One Style: Contemporary Duration: Six minutes As a young man trying to figure his way in the world of music, Miklós Rózsa (a Hollywood film composer) asked the French composer Arthur Honegger “How are we composers expected to make a living?” “Film music,” he said. “What?” I asked incredulously. I was unable to believe that Arthur Honegger, the composer of King David, Judith and other great symphonic frescos, of symphonic poems and chamber music, could write music for films. I was thinking of the musicals I had seen in Germany and of films like The Blue Angel, so I asked him if he meant foxtrots and popular songs. He laughed again. “Nothing like that,” he said, ‘I write serious music.’ As a young man, Honegger was part of a group of renegade composers in Paris grouped around the avant-garde poet Jean Cocteau called “Les Six.” Unlike, the other composers in “Les Six,” Honegger’s music is weightier and less flippant. In the 1920s, Honegger worked on three short orchestral pieces that he called Mouvements symphonique. In his autobiography, I am a Composer, he recounts his intent with the first: To tell the truth, In Pacific I was on the trail of a very abstract and quite ideal concept, by giving the impression of a mathematical acceleration of rhythm, while the movement itself slowed. It was only after he wrote the work that he gave it the title. “A rather romantic idea crossed my mind, and when the work was finished, I wrote the title, Pacific 231, which indicates a locomotive for heavy loads and high speed.” Given a title, people heard things that weren’t there. -

Louis Vierne's Pièces De Fantaisie, Opp. 51, 53, 54, and 55

LOUIS VIERNE’S PIÈCES DE FANTAISIE, OPP. 51, 53, 54, AND 55: INFLUENCE FROM CLAUDE DEBUSSY AND STANDARD NINETEENTH-CENTURY PRACTICES Hyun Kyung Lee, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: Jesse Eschbach, Major Professor Charles Brown, Related Field Professor Steve Harlos, Committee Member Justin Lavacek, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies of the College of Music Warren Henry, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Lee, Hyun Kyung. Louis Vierne’s Pièces de Fantaisie, Opp. 51, 53, 54, and 55: Influence from Claude Debussy and Standard Nineteenth-Century Practices. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2016, 47 pp., 2 tables, 43 musical examples, references, 23 titles. The purpose of this research is to document how Claude Debussy’s compositional style was used in Louis Vierne’s organ music in the early twentieth century. In addition, this research seeks standard nineteenth-century practices in Vierne’s music. Vierne lived at the same time as Debussy, who largely influenced his music. Nevertheless, his practices were varied on the basis of Vierne’s own musical ideas and development, which were influenced by established nineteenth-century practices. This research focuses on the music of Louis Vierne’s Pièces de fantaisie, Opp. 51, 53, 54, and 55 (1926-1927). In order to examine Debussy’s practices and standard nineteenth-century practices, this project will concentrate on a stylistic analysis that demonstrates innovations in melody, harmony, and mode compared to the existing musical styles. -

In This August, 2019 Issue the Dean's Column

Website: http://detroitago.org/ Visit Us on Facebook In This August, 2019 Issue The Dean’s Column Members News & Events (“The List”) Chapter News & Events For Sale The Dean’s Column I really can’t believe how summer has slipped away. Hoping it’s been a good summer for everyone and an opportunity for us to re-charge the batteries for the coming fall and Advent season. In the midst of choirs starting up again, preparation for special Advent and Christmas music, don’t forget about AGO programming. Andrew Herbruck, our Sub-Dean, has been working very hard this summer to put a schedule together for the coming year. And it is packed with great events. You will not want to miss any of them. In addition to the usual events including Epiphany banquet, organ crawl, installation of officers, scholarship auditions and scholarship/membership recital, there are two exciting recitals in the fall, a lecture/recital on music of Vierne and the list goes on and on. A special thank you to Andrew for his hard work on this endeavor. Speaking of installation of officers, this evening promises to be a delightful one. Wednesday, October 23 will be our annual installation of officers and board members for the new year. The evening includes a dinner sponsored by the host church, St. Paul’s UMC in Rochester and a recital by Johan Vexo, organist at Notre Dame/Paris. You will not want to miss this evening of good fellowship, friendship, sharing stories with colleagues and beautiful music. So please, if you have not done so, mark your calendars now for October 23 and save that date.