Berg's Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Music of Ernst Toch

THE CHORAL MUSIC OF ERNST TOCH By MIRIAM SUSAN ZACH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTL^L FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1993 Copyright 1993 by Miriam Susan Zach ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to Mikesch Miicke, life-partner and architect, for his patience, encouragement, and introduction to Venturi's thought. His ability to clarify mysteries of computers and the German language made this dissertation a reaUty. She would like to express her deepest gratitude to her parents, Margaret Munster Zach and Herbert William Zach, for a lifetime of support and for advocating the research, teaching, and performance of music. She feels fortunate to have had the opportunity to study music history and Uterature wdth Dr. David Z. Kushner, a master teacher, pianist, and researcher, a mentor who cares. The author is grateful to Dr. Otto W. Johnston for his persistence to help her develop a cogent argument, for responding promptly with thoughtful insights that focused fragmentary ideas, and his humor during the long process. She would also like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Budd Udell, Dr. Arthur Jennings, Dr. PhyUis Dorman, Dr. Russell Robinson, and Professor Reid Poole for their counsel and collective effort to teach her how to fish. She would like to honor Dr. Robert and MilUe Ramey for their encouraging presence and thoughtfulness. Marsha Berman and Stephen Fry at the UCLA Toch Archive gave their time and expertise during the author's two visits to the collection, and made long-distance research possible. -

17 by Francis Mallett and Simon Obert on 20 June 1962 Johanna

Beiträge A Case of Mistaken Identity? The Jalowetz Portrait by Richard Gerstl by Francis Mallett and Simon Obert On 20 June 1962 Johanna Jalowetz, the widow of the conductor and Schoenberg pupil Heinrich Jalowetz (d. 1946), wrote a letter to the art historian Otto Breicha. In those years Breicha was conducting research into the painter Richard Gerstl, in particular gathering information for a cata- logue of his works. In this connection he turned to Johanna Jalowetz, knowing that she owned “a painting by the artist.”1 Johanna Jalowetz re- sponded to his questions by noting that she possessed a Gerstl self-portrait, a “pointillist drawing” in ink on paper that probably “dates from the year 1906/7.” It bore, she continued, an “extraordinary resemblance” to the artist and was “a gift from him.”2 But she then added a paragraph whose contents can only have taken Breicha by surprise: At the same time, Gerstl painted to order a life-size three-quarter-length oil portrait of my husband in a pointillist technique. When we moved away from Vienna we left the said portrait for safekeeping with a relative, Alois Kurzweil. Our many changes of residence (at that time an opera conductor’s lot) made it impossible for us to look after the painting. And by the time we became more settled, after the First World War, we had lost all contact with and trace of Alois Kurzweil.3 1 Otto Breicha, letter of 4 June 1962 to Johanna Jalowetz, carbon copy in the Otto Breicha Archive, Leopold Museum, Vienna. We wish to thank Dominik Papst of the Leopold Museum for making available to us this and the following letter (see note 3). -

(C. 1960) Promotional Photograph Used in the 1960S

The Other Tchaikowsky Courtesy of Beatrice Harthan André Tchaikowsky (c. 1960) Promotional photograph used in the 1960s. The inscription reads, "To dear Wendy, with affection and fatherly feelings, André T." Wendy -- Beatrice Harthan -- was an older woman who knew many musicians. Through her contacts, André was able to expand his circle of friends. 184 Chapter 6 - Homeless in London (1960-1966) By the summer of 1960, the career launched with such great auspiciousness had changed drastically. It was fragmented and uncertain. Future possibilities in America had ended. Just about everyone whose backing and cooperation were essential had been alienated by André's off-stage behavior. Also, André had formed a dislike approaching mania for the grueling schedules and the social aspects of performing that went along with a big career. During the short span in which André can be considered as having a genuine career as a pianist, the three concert seasons from 1957 to 1960, he played over 500 performances. A simple calculation shows that, on the average, he played a concerto concert or gave a recital every other day for three seasons. This is an almost impossible work load for any musician, one that is bound to take its toll in quality of performance, attitude, and state of health. The machine-like demand for performing every second day absolutely precluded serious thoughts of composing, leaving him frustrated and dissatisfied. He retreated, needing the rest and the healing of a more casual life and the company of friends. A reduced career would provide more time for composing, and more and more he felt that composing was the real imperative in his career and in his life. -

The Other Tchaikowsky

The Other Tchaikowsky A biographical sketch of André Tchaikowsky David A. Ferré Cover painting: André Tchaikowsky courtesy of Milein Cosman (Photograph by Ken Grundy) About the cover The portrait of André Tchaikowsky at the keyboard was painted by Milein Cosman (Mrs. Hans Keller) in 1975. André had come to her home for a visit for the first time after growing a beard. She immediately suggested a portrait be made. It was completed in two hours, in a single sitting. When viewing the finished picture, André said "I'd love to look like that, but can it possibly be me?" Contents Preface Chapter 1 - The Legacy (1935-1982) Chapter 2 - The Beginning (1935-1939) Chapter 3 - Survival (1939-1945 Chapter 4 - Years of 'Training (1945-1957) Chapter 5 - A Career of Sorts (1957-1960) Chapter 6 - Homeless in London (1960-1966) Chapter 7 - The Hampstead Years (1966-1976) Chapter 8 - The Cumnor Years (1976-1982) Chapter 9 - Quodlibet Acknowledgments List of Compositions List of Recordings i Copyright 1991 and 2008 by David A. Ferré David A. Ferré 2238 Cozy Nook Road Chewelah, WA 99109 USA [email protected] http://AndreTchaikowsky.com Preface As I maneuvered my automobile through the dense Chelsea traffic, I noticed that my passenger had become strangely silent. When I sneaked a glance I saw that his eyes had narrowed and he held his mouth slightly open, as if ready to speak but unable to bring out the words. Finally, he managed a weak, "Would you say that again?" It was April 1985, and I had just arrived in London to enjoy six months of vacation and to fulfill an overdue promise to myself. -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

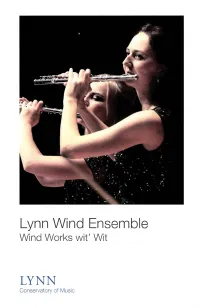

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College

Werner Herzog's Debt to Georg Buchner Franz A. Birgel Muhlenberg College The filmmaker Wemcr Herzog has been labeled eve1)1hing from a romantic, visionary idealist and seeker of transcendence to a reactionary. regressive fatalist and t)Tannical megalomaniac. Regardless of where viewers may place him within these e:-..1reme positions of the spectrum, they will presumably all admit that Herzog personifies the true auteur, a director whose unmistakable style and wor1dvie\v are recognizable in every one of his films, not to mention his being a filmmaker whose art and projected self-image merge to become one and the same. He has often asserted that film is the art of i1literates and should not be a subject of scholarly analysis: "People should look straight at a film. That's the only \vay to see one. Film is not the art of scholars, but of illiterates. And film culture is not analvsis, it is agitation of the mind. Movies come from the count!)' fair and circus, not from art and academicism" (Greenberg 174). Herzog wants his ideal viewers to be both mesmerized by his visual images and seduced into seeing reality through his eyes. In spite of his reference to fairgrounds as the source of filmmaking and his repeated claims that his ·work has its source in images, it became immediately transparent already after the release of his first feature film that literature played an important role in the development of his films, a fact which he usually downplays or effaces. Given Herzog's fascination with the extremes and mysteries of the human condition as well as his penchant for depicting outsiders and eccentrics, it comes as no surprise that he found a kindred spirit in Georg Buchner whom he has called "probably the most ingenious writer for the stage that we ever had" (Walsh 11). -

William Kentridge Brings 'Wozzeck' Into the Trenches

William Kentridge Brings ‘Wozzeck’ Into the Trenches The artist’s production of Berg’s brutal opera, updated to World War I, has come to the Metropolitan Opera. By Jason Farago (December 26, 2019) ”Credit...Devin Yalkin for The New York Times Three years ago, on a trip to Johannesburg, I had the chance to watch the artist William Kentridge working on a new production of Alban Berg’s knifelike opera “Wozzeck.” With a troupe of South African performers, Mr. Kentridge blocked out scenes from this bleak tale of a soldier driven to madness and murder — whose setting he was updating to the years around World War I, when it was written, through the hand-drawn animations and low-tech costumes that Metropolitan Opera audiences have seen in his stagings of Berg’s “Lulu” and Shostakovich’s “The Nose.” Some of what I saw in Mr. Kentridge’s studio has survived in “Wozzeck,” which opens at the Met on Friday. But he often works on multiple projects at once, and much of the material instead ended up in “The Head and the Load,” a historical pageant about the impact of World War I in Africa, which New York audiences saw last year at the Park Avenue Armory. Mr. Kentridge’s “Wozzeck” premiered at the Salzburg Festival in 2017. Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times called it “his most elegant and powerful operatic treatment yet.” At the Met, the Swedish baritone Peter Mattei will sing the title role for the first time; Elza van den Heever, like Mr. Kentridge from Johannesburg, plays his common-law wife, Marie; and Yannick Nézet- Séguin, the company’s music director, will conduct. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE COMPLETED SYMPHONIC COMPOSITIONS OF ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY DISSERTATION Volume I Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert L. -

Dissertation Body

Summary of Three Dissertation Recitals by Leo R. Singer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Aaron, Chair Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Joseph Gascho Professor Andrew Jennings Professor James Joyce Leo R. Singer [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2741-1104 © Leo R. Singer 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was made possible by the incredible faculty at the University of Michigan. Each course presented new information and ways of thinking, which in turn inspired the programming and performing choices for these three dissertation recitals. I would like to thank all the collaborators who worked tirelessly to make these performances special. I also must express my sincere and utmost gratitude to Professor Richard Aaron for his years of guidance, mentorship and inspiration. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, Scott and Rochelle, my sister, Julie, the rest of my family, and all of my friends for their unwavering support throughout the many ups and downs during my years of education. !ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv RECITALS I. MUSIC FROM FRANCE 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM 1 RECITAL 1 PROGRAM NOTES 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY 8 II. MUSIC FROM GERMANY AND AUSTRIA 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM 10 RECITAL 2 PROGRAM NOTES 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 III. MUSIC FROM AMERICA 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM 28 RECITAL 3 PROGRAM NOTES 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 !iii ABSTRACT In each of the three dissertation cello recitals, music from a different nation is featured. The first is music from France, the second from Germany and Austria, and the third from America. -

Ernst Toch Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft0z09n428 No online items Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library Special Collections staff and Kendra Wittreich; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 PASC-M 1 1 Title: Ernst Toch papers Collection number: PASC-M 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: German Physical Description: 44.0 linear ft.(88 boxes) Date (inclusive): ca. 1835-1988 Abstract: The Collection consists of materials relating to the Austrian-American composer, Ernst Toch. Included are music manuscripts and scores, books of his personal library, manuscripts, biographical material, correspondence, articles, essays, speeches, lectures, programs, clippings, photographs, sound recordings, financial records, and memorabilia. Also included are manuscripts and published works of other composers, as well as Lilly Toch's letters and lectures. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Toch, Ernst 1887-1964 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Woyzeck Bursts Onto the Ensemble Theatre Company Stage

MEDIA RELEASE CONTACT: Josh Gren [email protected] or 805.965.5400 x103 ELECTRIFYING TOM WAITS MUSICAL WOYZECK BURSTS ONTO THE ENSEMBLE THEATRE COMPANY STAGE March 25, 2015 – Santa Barbara, CA — The influential 19th Century play about a soldier fighting to retain his humanity has been transformed into a tender and carnivalesque musical by the legendary vocalist, Tom Waits. “If there’s one thing you can say about mankind,” the show begins, “there’s nothing kind about man.” The haunting opening phrase is the heart of the thrilling, bold, and contemporary English adaptation of Woyzeck – the classic German play, being presented at Ensemble Theatre Company this April. Inspired by the true story of a German soldier who was driven mad by army medical experiments and infidelity, Georg Büchner’s dynamic and influential 1837 poetic play was left unfinished after the untimely death of its author. In 2000, Waits and his wife and collaborator, Kathleen Brennan, resurrected the piece, wrote music for an avant-garde production in Denmark, and the resulting work became a Woyzeck musical and an album entitled “Blood Money.” “[The music] is flesh and bone, earthbound,” says Waits. “The songs are rooted in reality: jealousy, rage…I like a beautiful song that tells you terrible things. We all like bad news out of a pretty mouth.” Woyzeck runs at the New Vic Theater from April 16 – May 3 and opens Saturday, April 18. Jonathan Fox, who has served as ETC’s Executive Artistic Director since 2006, will direct the ambitious, wild, and long-awaited musical. “It’s one of the most unusual productions we’ve undertaken,” says Fox.