The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters / Priya Parker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis Release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit Weg Von Zu Hause 17,50 € Mai

Best-Nr. Künstler Album Preis release 0001 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von zu Hause 17,50 € Mai. 21 0002 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0003 100 Kilo Herz Stadt Land Flucht 19,00 € Jun. 21 0004 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0005 100 Kilo Herz Weit weg von Zuhause 17,50 € Jun. 21 0006 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0007 123 minut Les 19,00 € 0008 17 Hippies Anatomy 23,00 € 0009 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0010 187 Straßenbande Sampler 5 26,00 € Mai. 21 0011 A day to remember You're welcome (ltd.) 31,50 € Mrz. 21 0012 A day to remember You're welcome 23,00 € Mrz. 21 0013 Abba The studio albums 138,00 € 0014 Aborted Retrogore 20,00 € 0015 Abwärts V8 21,00 € Mrz. 21 0016 AC/DC Black Ice 20,00 € 0017 AC/DC Live At River Plate 28,50 € 0018 AC/DC Who made who 18,50 € 0019 AC/DC High voltage 19,00 € 0020 AC/DC Back in black 17,50 € 0021 AC/DC Who made who 15,00 € 0022 AC/DC Black ice 20,00 € 0023 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0024 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0025 AC/DC Power Up 55,00 € Nov. 20 0026 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0027 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0028 AC/DC Power Up Limited red 31,50 € Nov. 20 0029 AC/DC Power Up 27,50 € Nov. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

Perancangan Typeface Terinspirasi Dari Album Lost Forever // Lost Together

PERANCANGAN TYPEFACE TERINSPIRASI DARI ALBUM LOST FOREVER // LOST TOGETHER PENCIPTAAN Riza Lukmana PROGRAM STUDI S-1 DESAIN KOMUNIKASI VISUAL JURUSAN DESAIN FAKULTAS SENI RUPA INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2015 UPT PERPUSTAKAAN ISI YOGYAKARTA PERANCANGAN TYPEFACE TERINSPIRASI DARI ALBUM LOST FOREVER // LOST TOGETHER PENCIPTAAN Riza Lukmana NIM 1112108024 Tugas Akhir ini diajukan kepada Fakultas Seni Rupa Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta sebagai Salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana S-1 dalam bidang Desain Komunikasi Visual 2015 i UPT PERPUSTAKAAN ISI YOGYAKARTA Tugas Akhir berjudul PERANCANGAN TYPEFACE TERINSPIRASI DARI ALBUM LOST FOREVER // LOST TOGETHER diajukan oleh Riza Lukmana, NIM 1112108024, Program Studi S-1 Desain Komunikasi Visual, Jurusan Desain, Fakultas Seni Rupa Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta, telah disetujui Tim Pembina Tugas Akhir pada tanggal 1 Juli 2015 dan dinyatakan telah memenuhi syarat untuk diterima. Pembimbing I/Anggota FX. Widyatmoko, S.Sn., M.Sn. NIP 19750710 200501 1 001 Pembimbing II/Anggota Hesti Rahayu, S.Sn., MA. NIP 19740730 199802 2 001 Cognate/Anggota Indiria Maharsi, S.Sn., M.Sn. NIP 19720909 200812 1 001 Ketua Program Studi S-1 Desain Komunikasi Visual/Ketua/Anggota Drs. Hartono Karnadi, M.Sn. NIP 19650209 199512 1 001 Ketua Jurusan Desain Drs. Baskoro SB, M.Sn. NIP 19650522 199203 1 003 Mengetahui, Dekan Fakultas Seni Rupa Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta Dr. Suastiwi, M.Des. NIP 19590802 198803 2 002 ii UPT PERPUSTAKAAN ISI YOGYAKARTA PERNYATAAN KEASLIAN Dengan ini saya menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa tugas akhir dengan judul PERANCANGAN TYPEFACE TERINSPIRASI DARI ALBUM LOST FOREVER // LOST TOGETHER merupakan hasil penelitian, pemikiran, dan pemaparan asli dari penulis sendiri. -

Nr Kat EAN Code Artist Title Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data Premiery Repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816432 190758164328 '77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 9985848 5051099858480 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us CD Longplay 1 2015-10-30 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262 886976362621 *NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882 888750258823 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 19075906532 190759065327 00 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 88875143462 888751434622 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 88697919802 886979198029 2CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 88843087812 888430878129 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88875052342 888750523426 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88725409442 887254094425 2CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 19075869722 190758697222 2CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 88883745419 888837454193 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 88985349122 889853491223 2CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 88985461102 889854611026 2CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 19075818232 190758182322 4 Times Baroque Caught in Italian Virtuosity CD Longplay 1 2018-03-09 CLASSICAL 88985330932 889853309320 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

It's Harvest Time Again

SEPT. 22-28, 2016 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFORTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM ----------------------Feature • Columbia City Haunted Jail --------------------- It’s Harvest Time Again By Mark Hunter “Each year The Master likes to, ahem, dom body parts?” I said. revamp the place,” the man said. “Some new “As you like it, sir.” It’s harvest time at the Columbia City paint, a couple of throw pillows.” Right. I like it when I’m out of there. Haunted Jail. And the crop is blood. “Don’t you mean fresh blood and ran- The place gives me the creeps, probably Yes, it’s hard to believe because it’s lousy with creepers, but it’s been a full year since or stalkers, as the locals call them. the batty one ordered his Even in the relatively well-lighted servants to sow the seeds of gloom, I had the sense I was being death in the halls of the jail. followed, either by practiced acro- But what’s time to a vam- bats or zombie contortionists. Turns pire? The flutter of a wing? out the zombie contortionists were October 15 | 8pm Don’t bother asking Deimos on a break and out of their autopsy Nosferatu. He doesn’t wear a room cages. watch. The tour led up a narrow stair- HE R E COM E The MUMMI E S A year ago Deimos re- case to the third floor where only Sponsored by Jefferson Pointe leased his fellow bloodsuck- VIPs are allowed, for a small fee of and Fort Wayne CW ers to gain control of the zom- course. -

Neoliberal Gothic

i Neoliberal Gothic 99781526113443_pi-214.indd781526113443_pi-214.indd i 22/22/2017/22/2017 22:21:46:21:46 PPMM ii T e Series’ Board of General Editors Elisabeth Bronfen, University of Zurich, Switzerland Steven Bruhm, University of Western Ontario, Canada Ken Gelder, University of Melbourne, Australia Jerrold Hogle , University of Arizona, USA (Chair) Avril Horner , Kingston University, UK William Hughes, Bath Spa University, UK T e Editorial Advisory Board Glennis Byron, University of Stirling, Scotland Robert Miles, University of Victoria, Canada David Punter, University of Bristol, England Andrew Smith, University of Glamorgan, Wales Anne Williams, University of Georgia, USA Previously published Monstrous media/ spectral subjects: imaging gothic f om the nineteenth century to the present Edited by Fred Bot ing and Catherine Spooner Globalgothic Edited by Glennis Byron EcoGothic Edited by Andrew Smith and William Hughes Each volume in this series contains new essays on the many forms assumed by – as well as the most important themes and topics in – the ever-expanding range of international ‘gothic’ f ctions from the eighteenth to the twenty- f rst century. Launched by leading members of the International Gothic Association (IGA) and some editors and advisory board members of its journal, Gothic Studies , this series thus of ers cut ing- edge analyses of the great many variations in the gothic mode over time and all over the world, whether these have occurred in literature, f lm, theatre, art, several forms of cybernetic media, or other manifestations ranging from ‘goth’ group identities to avant garde displays of aesthetic and even political critique. T e ‘gothic story’ began in earnest in 1760s England, both in f ction and in drama, with Horace Walpole’s ef orts to combine the ‘ancient’ or supernatural and the ‘modern’ or realistic romance. -

Chapter Five “Days of Future Passed”

Chapter Five “Days of Future Passed” Chapter 5 Overview The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) was a dramatic departure from previous rock music. No longer restricted to teenage dance music, the Sgt. Pepper album ushered in a period of music for listening or "album oriented rock" (AOR) Classic concept albums such as Days of Future Passed by the Moody Blues used orchestral settings and Pink Floyd employed electronic experimentation and the elements of the avant garde. Rock musicals such as Hair, (1967) and rock operas such as Tommy, (1968) elevated rock music to a much higher artistic level. In general, pieces become longer, more complex and experimental often using electronic music, noise, and non-western musical idioms. The hippie subculture's emphasis on visual and musical diversity encouraged rock to splinter into many sub-styles such as heavy metal, glitter/glam, progressive rock, and theatre rock. 1 The End of the Hippie Counter-Culture Movement By 1970, signs that the hippie counterculture was declining became apparent. 1. During a ten month period rock lost three of its legends: Jimi Hendrix, September 18, 1970; Janis Joplin October 4, 1970; and Jim Morrison July 3, 1971 all the result of drug related causes. 2. In 1970 four anti-war protesters were shot to death by National Guardsmen at Kent State University. Most universities were shut down in the resulting nationwide campus protests. Kent State effectively brought to an end the free speech movement at American Universities. 3. The Beatles, in many ways the spokesmen of the counterculture, broke up in 1970. -

Page 1 C R O S S I N G S B E T W E E N T H E

OCT 12 14 CROSSINGS BETWEEN THE PROXIMATE AND REMOTE MARFA 2017 ACSA FALL CONFERENCE Between Worlds: Art and Architecture I Date: Friday, October 13, 2017 Time: 8:30:00 AM - 10:00:00 AM Location : Binder Gallery I Bad Acting Architecture Eric Olsen, Woodbury University This paper, entitled Bad Acting Architecture, explicates a relationship between art practice and architecture –an implicit argument of “Crossings Between the Proximate and Remote.” From the artistic economies of gentrified enclaves to transformative processes that critique and embellish the built environment, the late artist Mike Kelley’s concept of bad acting—not behaving according to proper disciplinary roles—provides an heretofore untapped avenue of architectural inquiry. Bad Acting implies both mischief and melodrama. Neither offering claims to universal values nor directly engaging processes of social action, it allows for contingent collisions between high and low art to produce ludic zones of informal design and collateral criticality. The posture of bad acting produces space, at multiple scales and sites, through unorthodox methodologies that explore architecture through the artist’s irreverent lens. Between a creative economy’s ability to reterritorialize space and urban designers thinking about ways to transform moribund landscapes, the missing catalyst in this discussion is the artist herself. If artists define new territories through their very inhabitation of a place, might not the work they produce also describe alternative design practices for the transforming the built environment? A large quantity of Kelley’s work, such as Sod and Sodie Sock Comp O.S.O. (1980), Proposal for the Decoration of an Island of Conference Rooms (with Copy Room) for an Advertising Agency Designed by Frank Gehry (1991), Educational Complex (1995), Sublevel (1998), Kandors (1999-2011), Petting Zoo (2007), and Mobile Homestead (2005-2013), indicates that architecture is a significant focus within his prolific and highly diverse artistic production. -

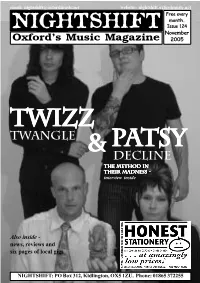

Issue 124.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 124 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 TwizzTwizzTwizz twangle &&& pppaaatststsyyy decline The method in their madness - interview inside Also inside - news, reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] SEXY BREAKFAST have split up. The band, who have been a mainstay of the local scene for almost ten years, bowed out with a gig at the Zodiac supporting The Paddingtons last month. Frontman Joe Swarbrick is set to form a new band; in the interim he will be playing a solo gig at the Port Mahon on Saturday 26th November. The Barn at The Red Lion, Witney THE EVENINGS head off on a UK tour Live Music November Programme this month to promote their new ‘Louder In the Dark’ EP on Brainlove Records. The Fri 4th RUBBER MONKEYS THE YOUNG KNIVES head out on their new EP is officially released on November th th Sat 5 SLEEPWALKER biggest ever UK tour this month to 7 ; the band play at the Cellar on th rd Sun 6 DEAD MEN’S SHOES promote new single, ‘The Decision’, on Thursday 3 November with support th Transgressive Records. The new single is a from Applicants, Open Mouth and Fri 11 THE WORRIED MEN th re-recording of 2004’s release on Hanging Napoleon III. The Evenings’ ‘Let’s Go Sat 12 GATOR HIGHWAY th Out With the Cool Kids, which topped Remixed’ album is now set to be released Sun 13 MICHAEL Nightshift’s end of year Top 20 chart. -

The Blackout Argument Have Heart Touché Amoré Deadlock Beatsteaks Mogwai Trail of Dead Red Tape Parade Oceano Times of Grace

26 FEB/MAR 11 FOR FREE THE BLACKOUT ARGUMENT HAVE HEART TOUCHÉ AMORÉ DEADLOCK BEATSTEAKS MOGWAI TRAIL OF DEAD RED TAPE PARADE OCEANO TIMES OF GRACE Fuze_Titel_No.26.indd 2 07.01.11 15:08 02Fuze26.indd 2 06.01.11 10:40 empD_adv_fuze_0111.indd 2 05.01.11 15:00 index IMPRESSUM 05 MOGWAI Der letzte Tee geht auf Margaret Thatcher. Fuze Magazine Thomas Renz, P.O.Box 11 04 20 07 ZWEITAUSENDZEHN 42664 Solingen, Germany Darf ich vorstellen? 20 HAVE HEART (Pakete an: Fuze Magazine, 08 LONG DISTANCE CALLING Coming of age. Hochstraße 15, 42697 Solingen) My linernotes. Fon 0212 383 18 29, Fax 0212 383 18 30 22 THE BLACKOUT ARGUMENT fuze-magazine.de, myspace.com/fuzemag 09 I HATE OUR FREEDOM Nachsitzen als Fleißaufgabe. Namedropping. Redaktion: 24 TRAIL OF DEAD Thomas Renz, [email protected] 10 ANTAGONIST Abseits des Status quo. Anzeigen, Verlag: My friends @ MySpace. 25 OCEANO Joachim Hiller, [email protected] 11 THE CHARIOT Und täglich grüßt das Murmeltier. Marketing, Vertrieb, Anzeigen: Pants down – Christian edition. Kai Rostock, [email protected] 26 TIMES OF GRACE 11 THE BLACK DAHLIA MURDER Die Hymnen eines beschäftigten Mannes. Verlag & Herausgeber: Ask the merch guy. Joachim Hiller, Hochstraße 15, 27 RED TAPE PARADE 42697 Solingen, Germany 12 EARTHSHIP / ABRAHAM Hardcore ist eine Blase. Labelmates. V.i.S.d.P.: Thomas Renz (Für den Inhalt von 28 DEADLOCK 13 NONE MORE BLACK Weniger denken, mehr Weniger. namentlich gekennzeichneten Artikeln ist der/ Journalistenschule. die VerfasserIn verantwortlich. Sie geben nicht 29 AKELA unbedingt die Meinung der Redaktion wieder.) 14 EARACHE RECORDS Unbekanntes Neuland. -

Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley A

Building Home: Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Sean P. Gleason August 2017 © 2017 Sean P. Gleason. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled Building Home: Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley by SEAN P. GLEASON has been approved for the School of Communication Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Devika Chawla Professor of Communication Studies Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii Abstract GLEASON, SEAN P., Ph.D., August 2017, Communication Studies Building Home: Vernacular Architecture and Domestic Habit in the Ohio River Valley Director of Dissertation: Devika Chawla Dwelling entails the consumption of resources. Every day others die so that we may live. I realize this simple premise after fieldwork. For six months, during the spring and summer of 2016, I visited 13 southern Ohio homesteads interviewing an intergenerational population, ranging in age from 23-65, about their decision live off-grid in the Ohio River Valley as a form of environmental activism. During fieldwork, I helped participants mix sand, straw, and clay to create cob—one of the earliest-recorded building materials. I attended workshops on permaculture and tiny homes. My participants told me why they chose to build with rammed earth, citing examples from the 11th and 12th centuries. I learned about off-grid living and how to recycle rainwater. I built windows with salvaged wine bottles and framed walls from scrap tires.