Uganda's Tax on Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

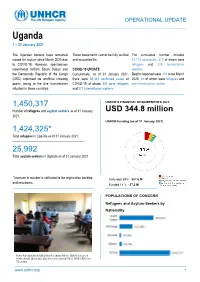

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Democracy Or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda

Journal of African Democracy and Development Vol. 1, Issue 2, 2017, 109-127, www.kas.de/Uganda/en/ Democracy or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda Jacqueline Adongo Masengoa Abstract This paper examines the discourses shaping the introduction of multi-party politics in Uganda and how it is linked to democracy and development. The paper shows that most Ugandans prefer multi-party politics because they link it to democracy and development. This is why when the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M) captured power in 1986 and multi-party politics was abolished, there was pressure from the public to reinstate it through the 2005 referendum in which the people voted in favour of a multi- party system. The paper also examines the role played by Ugandan politicians and professional middle class such as writers and literary critics (local agency) in the return of multi-party politics in Uganda. It explores their contribution of in re-democratising the Ugandan state and argues that despite the common belief that multi-party politics aids democracy and development, it might not be the case in Uganda. Multi-party politics in Uganda has turned out not to necessarily mean democracy, and eventually development. The paper grapples with the question of what democracy is in Uganda and/ or to Ugandans, and the extent to which the Ugandan political arena can be considered democratic, and as a fertile ground for development. Did the return to multi- party politics in Uganda guarantee democracy or is it just a fallacy? What is the relationship between democracy and development in Uganda? Keywords: Multi-party politics, democracy, Fallacy, Uganda 1. -

The Lord's Resistance Army in Central Africa

The Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa A short timeline May 2009 Yoweri Museveni, leader of AP Photo Alice Lakwena, a young Acholi woman from northern the National Resistance 1986 Uganda declares herself to be under the orders of Christian Army, overthrows President spirits, creates the rebel group the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, Milton Obote and becomes and declares war against Museveni’s government. president of Uganda. After taking power, President Another rebel group, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army, Museveni, a southerner, or UPDA, launches a rebellion against Museveni. Joseph begins systematically President Yoweri Museveni Kony, reportedly a cousin of Alice Lakwena, serves as a rooting out ‘enemies’ hailing Catholic preacher to the UPDA. from the Acholi ethnic group of northern Uganda. Kony, despite claiming to AP Photo defend the rights of the Lakwena is defeated, and she flees to Kenya. Kony recruits her 1987-88 Acholi in northern Uganda remaining forces and forms the Uganda People’s Democratic by waging war against the Christian Army, which later becomes the Lord’s Resistance Ugandan government, Army, or LRA. 1991 launches a campaign of extreme brutality against them, murdering and LRA Leader Joseph Kony IRIN The Sudanese government mutilating civilians, pillaging begins to provide direct villages, and abducting children to fill his ranks. support to the LRA. In return, the LRA supports 1993-4 Khartoum’s war against the Sudan People’s Liberation IRIN Army in southern Sudan. SPLA Rebels in Southern Sudan 1996 The U.S. government Protected village in northern Uganda places the LRA Stating its intent to prevent looting and abductions by the on a list of terrorist LRA, the Ugandan government forces more than two million organizations. -

Amin: His Seizure and Rule in Uganda. James Francis Hanlon University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Amin: his seizure and rule in Uganda. James Francis Hanlon University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hanlon, James Francis, "Amin: his seizure and rule in Uganda." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2464. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2464 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMIN: HIS SEIZURE AND RULE IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented By James Francis Hanlon Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS July 1974 Major Subject — Political Science AMIN: HIS SEIZURE AND RULE IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented By James Francis Hanlon Approved as to style and content by: Pro i . Edward E. Feit. Chairman of Committee Prof. Michael Ford, member ^ Prof. Ferenc Vali, Member /£ S J \ Dr. Glen Gordon, Chairman, Department of Political Science July 1974 CONTENTS Introduction I. Uganda: Physical History II. Ethnic Groups III. Society: Its Constituent Parts IV. Bureaucrats With Weapons A. Police B . Army V. Search For Unity A. Buganda vs, Ohote B. Ideology and Force vi. ArmPiglti^edhyithe-.Jiiternet Archive VII. Politics Without lil3 r 2Qj 5 (1970-72) VIII. Politics and Foreign Affairs IX. Politics of Amin: 1973-74 C one ius i on https://archive.org/details/aminhisseizureruOOhanl , INTRODUCTION The following is an exposition of Edward. -

Download the Transcript

SOMALIA-2021/05/21 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION WEBINAR ELECTIONS AND CRISES IN SOMALIA AND ETHIOPIA Washington, D.C. Thursday, May 20, 2021 PARTICIPANTS: Moderator: VANDA FELBAB-BROWN Senior Fellow and Director, Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors The Brookings Institution Panelists: ABDIRAHMAN AYNTE Co-founder and Managing Director Laasfort Consulting Group BRONWEN MORRISON Senior Director Center for Global Security and Stabilization Dexis Consulting Group LIDET TADESSE Policy Officer, Security Resilience Programme European Centre for Development Policy Management * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 1800 Diagonal Road, Suite 600 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 SOMALIA-2021/05/21 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MS. FELBAB-BROWN: Good morning. Good afternoon. I am Vanda Felbab-Brown, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of the Brookings Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors and co-director of our Africa Security Initiative. I am delighted that you are all joining us today for our webinar on Crises and Elections in Ethiopia and Somalia and the regional setting of Horn of Africa, a very important issue that has been very dramatic and visibly in the news and, of course, unfolding in very important ways in the region. We have an absolutely terrific panel to discuss those very complex, very important issues with us that I will introduce in a minute. You know, I mentioned that Ethiopia and Somalia have been going through some very dramatic events in the past few months including, in the case of Somalia in the past few days and weeks. There are, of course, more dramatic changes in both countries taking place in the past few years such as in the past five years that have preceded those dramatic crises and to some extent, influenced them to other extent, but have not been able to prevent them. -

Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2005

United Nations S/2005/89 Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2005 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Somalia I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to the statement of the President of the Security Council of 31 October 2001 (S/PRST/2001/30), in which the Council requested me to submit reports on a quarterly basis on the situation in Somalia. The report focuses on developments regarding the national reconciliation process in Somalia since my previous report, of 8 October 2004 (S/2004/804). It also provides an update on the security situation as well as the humanitarian and development activities of United Nations programmes and agencies in Somalia. II. The formation of the Transitional Federal Government 2. The Somali National Reconciliation Conference concluded on 14 October 2004 with the swearing-in of Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed as the President of Somalia. He was elected by the members of the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia on 10 October 2004 after three rounds of voting. In the final round, Colonel Yusuf obtained 189 votes while the runner-up candidate, Abdullahi Ahmed Addow, obtained 79 votes. Mr. Addow accepted the outcome and pledged to cooperate with the President. Prior to the vote, all 26 presidential candidates signed a declaration to support the elected President and to demobilize their militias. 3. On 3 November, President Yusuf appointed Ali Mohammed Gedi, a veterinarian and member of the Hawiye clan, predominant in Mogadishu, as Prime Minister of the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia. 4. During the first week of December, Prime Minister Gedi announced the appointment of some 73 Ministers, Ministers of State and Assistant Ministers. -

Security Council EOSG / CENTRAL

United Nations J/2004/115 Security Council Distr.: General 12 February 2004 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation ii/Somalia I. Introduction 1. In its presidential statement of 31 October 2001 (S/PRST/2001/30), the Security Council requested me to submit reports, at least every four months, on the situation in Somalia and the efforts to promote the peace process. 2. The present report covers developments since my previous report, dated 13 October 2003 (S/2003/987). Its main focus is the challenges faced and the progress made by the Somali national reconciliation process, which has been ongoing in Kenya since October 2002 under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), with support from the international community. The report also provides an update on the political and security situation in Somalia and the humanitarian and development activities of United Nations programmes and agencies in the country. II. Somali national reconciliation process 3. By mid-September 2003, developments at the Somalia National Reconciliation Conference at Mbagathi, Kenya, led to an impasse over the contested adoption of a charter (see S/2003/987, paras. 13-18). Some of the leaders, including the President of the Transitional National Government, Abdikassim Salad Hassan, Colonel Barre Aden Shire of the Juba Valley Alliance (JVA), Mohamed Ibrahim Habsade of the Rahanwein Resistance Army (RRA), Osman Hassan Ali ("Atto") and Musse Sudi ("Yalahow") rejected the adoption, and returned to Somalia. On 30 September, a group of them announced the formation of the National Salvation Council consisting of 12 factions under the chairmanship of Musse Sudi. -

“Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-Election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda WATCH “Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33139 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JANAURY 2016 ISBN 978-1-6231-33139 “Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary of Acronyms and Terms ........................................................................................ ii Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

African Leadership Forum 2015

AFRICAN LEADERSHIP FORUM 2015 “Moving Towards an inTegraTed africa” DaR es salaam, Tanzania 30 JUly 2015 Institute of African Leadership for The United Republic of Tanzania Sustainable Development Benjamin William Mkapa Former President of the United Republic of Tanzania 3 Table of Contents Acronyms and abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 1. The Opening Session ..................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Welcome by H.E. Benjamin Mkapa .............................................................................. 10 1.2 Introduction of Keynote Speaker ................................................................................ 12 1.3 Keynote Address by H.E. Yoweri Museveni, President of Uganda —The Challenges of Integrating Africa to Achieve Sustainable Growth and Transformation and Ensure that Africa and Africans Contribute to and Benefit from the “Global Pie” ...................................................................................... 13 1.4 Plenary Discussion: Moving Towards an Integrated Africa .................................... 19 2. Panel Discussions ............................................................................................................ 26 2.1 Session I: Establishing and Strengthening Institutions to Support -

The Cotter Pin by Andrew Rice

AR-7 Sub-Saharan Africa Andrew Rice is a Fellow of the Institute studying life, politics and development in ICWA Uganda and environs. LETTERS The Cotter Pin By Andrew Rice JANUARY 1, 2003 Since 1925 the Institute of KAMPALA, Uganda—The sirens’ wail was getting louder. Outside the Nile Current World Affairs (the Crane- Hotel’s International Conference Center, the hexagonal slab of port-holed con- Rogers Foundation) has provided crete where three decades of Ugandan presidents have welcomed important visi- long-term fellowships to enable tors, the blue-uniformed honor guard stiffened to attention in the late-November outstanding young professionals heat. The ministers and generals took their places on the steps. Reporters pulled to live outside the United States out their notebooks, news photographers lifted their cameras to their shoulders. and write about international All eyes fixed on the front gates. The presidents were about to arrive. areas and issues. An exempt operating foundation endowed by A little after 10a.m., a pickup truck peeled through the gates, loaded with the late Charles R. Crane, the security officers, machine guns at the ready. A pair of motorcycle police followed, Institute is also supported by leading the way for the black Mercedes limousine. It glided to the front of the contributions from like-minded building and stopped. individuals and foundations. The doors of the limousine opened, and the presidents emerged. From one side, His Excellency Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, president of Kenya, dressed in his customary fashion: a dark blue suit and a garish multicolored necktie. From TRUSTEES the other, His Excellency Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, president of Uganda, nattily Bryn Barnard attired as always. -

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

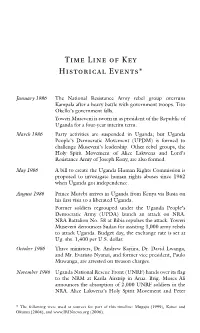

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006).