The Cotter Pin by Andrew Rice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

The Applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye Filled This Application by Notice of Motion Under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution Of

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA CRIMINAL APPLICATION NO. 83 OF 2016 (ARISING FROM MOR-OO-CR-AA-016/2016 AND NAK-A-NO.14/2016) COL (RTD) DR. KIZZA BESIGYE:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: APPLICANT VERSUS UGANDA::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: RESPONDENT. BEFORE: HON JUSTICE MR. MASALU MUSENE RULING The applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye filled this application by Notice of Motion under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution of Uganda, section 14 of the Trial on Indictments Act, cap 23 and rule 2 of the Judicature (criminal procedure)(applications rules S.I 13 -8) and all applicable laws. It is an application for bail pending trial. The applicant was represented by Mr. Ernest Kalibala together with Mr. Frederick Mpaga while the state was represented by M/S Florence Akello, principal state attorney and Mr. Brian Kalinaki also principal state attorney from the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The grounds in support of the application are outlined in the affidavit of the applicant, Col (Rtd) Kizza Besigye of Buyinja Zone, Nangabo sub-county, Kasangati in Wakiso district. In summary, they are as follows; 1. That on 13th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates Court of Moroto at Moroto and remanded in custody. 1 2. That on 18th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates court of Nakawa at Nakawa and remanded in custody. 3. That the applicant is a 60 year old responsible and respectable citizen of Uganda, a retired colonel in the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces and former presidential candidate in the 2016 presidential elections where he represented the Forum for Democratic Change, a dully registered political party. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

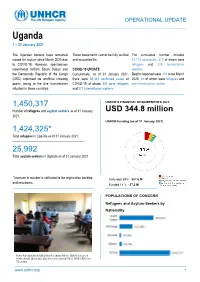

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations. -

Conversation Living Feminist Politics - Amina Mama Interviews Winnie Byanyima

Conversation Living Feminist Politics - Amina Mama interviews Winnie Byanyima Winnie Byanyima is MP for Mbarara Municipality in Western Uganda. The daughter of two well-known politicians, she was a gifted scholar and won awards to pursue graduate studies in aeronautical engineering. However, she chose to join the National Resistance Movement under Museveni's leadership, and later became one of the first women to stand successfully for direct elections. Winnie is best known for her gender advocacy work with non- governmental organisations, her anti-corruption campaigns, and her opposition to Uganda's involvement in the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. She is currently affiliated to the African Gender Institute, where she is writing a memoir of three generations of women – her grandmother, her mother and her own life in politics. Here she is interviewed by Amina Mama on behalf of Feminist Africa. Amina Mama: Let's begin by talking about your early life, and some of the formative influences. Winnie Byanyima: I grew up pretty much my father's daughter. I admired him very much, and people said I was like him. I had a more difficult relationship with my mother. But in the last few years as I've tried to reflect on who I am and why I believe the things that I believe, I've found myself coming back to my mother and my grandmother, and having to face the fact that I take a lot from those women. It's tough, because it means that I must recognise all that I didn't take as important about my mother's struggles. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Democracy Or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda

Journal of African Democracy and Development Vol. 1, Issue 2, 2017, 109-127, www.kas.de/Uganda/en/ Democracy or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda Jacqueline Adongo Masengoa Abstract This paper examines the discourses shaping the introduction of multi-party politics in Uganda and how it is linked to democracy and development. The paper shows that most Ugandans prefer multi-party politics because they link it to democracy and development. This is why when the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M) captured power in 1986 and multi-party politics was abolished, there was pressure from the public to reinstate it through the 2005 referendum in which the people voted in favour of a multi- party system. The paper also examines the role played by Ugandan politicians and professional middle class such as writers and literary critics (local agency) in the return of multi-party politics in Uganda. It explores their contribution of in re-democratising the Ugandan state and argues that despite the common belief that multi-party politics aids democracy and development, it might not be the case in Uganda. Multi-party politics in Uganda has turned out not to necessarily mean democracy, and eventually development. The paper grapples with the question of what democracy is in Uganda and/ or to Ugandans, and the extent to which the Ugandan political arena can be considered democratic, and as a fertile ground for development. Did the return to multi- party politics in Uganda guarantee democracy or is it just a fallacy? What is the relationship between democracy and development in Uganda? Keywords: Multi-party politics, democracy, Fallacy, Uganda 1. -

The Trials and Tribulations of Rtd. Col. Dr. Kizza Besigye and 22 Others

The Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda THE TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF RTD. COL. DR. KIZZA BESIGYE AND 22 OTHERS A Critical Evaluation of the Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda Ronald Naluwairo Copyright © Human Rights &Peace Centre, 2006 ISBN 9970-511-00-8 HURIPEC Working Paper No.1. October, 2006 The Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda The Role of the General Court Martial in the Administration of Justice in Uganda Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................ii Summary of the Report and Policy Recommendations.......................... iii List of Acronyms.......................................................................................vi I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND TO THE TRIALS OF BESIGYE & 22 OTHERS.........3 III. THE LAW GOVERNING THE GENERAL COURT MARTIAL............12 A. Establishment, Composition and Tenure ...........................................13 B. Quorum and Decision Making............................................................14 C. Jurisdiction ....................................................................................... 14 D. Guarantees for the Right to a Fair Hearing and a Just Trial ..............17 IV. THE RELATIONSHIP WITH CIVILIAN COURTS..............................19 V. EVALUATION OF THE ROLE OF THE GENERAL COURT -

The Republic of Uganda in the Supreme

5 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE SUPREME COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION PETITION NO. O1 OF 2016 (CORAM: KATUREEBE, C.J, TUMWESIGYE, KISAAKYE, 10 ARACH AMOKO, NSHIMYE, MWANGUSYA,OPIO-AWERI, MWONDHA, TIBATEMWA-EKIRIKUBINZA, JJ.SC.) AMAMA MBABAZI …………………………………….PETITIONER VERSUS 15 YOWERI KAGUTA MUSEVENI ……………. 1stRESPONDENT ELECTORAL COMMISSION ……………… 2ndRESPONDENT THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ………………… 3rd RESPONDENT PROFESSOR OLOKA ONYANGO & 8 ORS………..AMICI 20 CURIAE DETAILED REASONS FOR THE JUDGMENT OF THE COURT The Petitioner, who was one of the candidates in the presidential 25 election that was held on the 18th February, 2016 petitioned the 1 5 Supreme Court under the Constitution, the Presidential Elections Act, 2000 and the Electoral Commission Act, 1997 (hereinafterreferred to as the PEA and the ECA, respectively). He challenged the result of the election and sought a declaration that Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, the 1st Respondent, was not 10 validly elected and an order that the election be annulled. On the 31st March 2016, we delivered our decision in line with the Constitutional timeline imposed on the Court to render its judgment within 30 days from the date of filing the petition. We were not, however, in a position to give detailed reasons for our 15 findings and conclusion. We found that the 1st Respondent was validly elected as President in accordance with Article 104 of the Constitution and Section 59 of the PEA. Accordingly, we unanimously dismissed the petition. We made no order as to costs. 20 We promised to give the detailed reasons at a later date, which we now give in this judgment. Background The 18thFebruary 2016 General Elections were the 3rd since the re-introduction of multiparty politics in Uganda as the country 25 shifted from the movement system. -

Politics and the Demographic Shift: the Role of the Opposition in Uganda

Africa Programme Meeting Summary Politics and the Demographic Shift: The Role of the Opposition in Uganda Speaker: Dr Kizza Besigye Leader, Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), Republic of Uganda Chair: Ben Shepherd Consulting Fellow, Africa Programme, Chatham House 9 September 2016 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2017. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Politics and the Demographic Shift: The Role of the Opposition in Uganda Introduction This meeting summary provides an overview of an event held at Chatham House, on 9 September 2016, with Dr Kizza Besigye, leader of Uganda’s main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). -

The Lord's Resistance Army in Central Africa

The Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa A short timeline May 2009 Yoweri Museveni, leader of AP Photo Alice Lakwena, a young Acholi woman from northern the National Resistance 1986 Uganda declares herself to be under the orders of Christian Army, overthrows President spirits, creates the rebel group the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, Milton Obote and becomes and declares war against Museveni’s government. president of Uganda. After taking power, President Another rebel group, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army, Museveni, a southerner, or UPDA, launches a rebellion against Museveni. Joseph begins systematically President Yoweri Museveni Kony, reportedly a cousin of Alice Lakwena, serves as a rooting out ‘enemies’ hailing Catholic preacher to the UPDA. from the Acholi ethnic group of northern Uganda. Kony, despite claiming to AP Photo defend the rights of the Lakwena is defeated, and she flees to Kenya. Kony recruits her 1987-88 Acholi in northern Uganda remaining forces and forms the Uganda People’s Democratic by waging war against the Christian Army, which later becomes the Lord’s Resistance Ugandan government, Army, or LRA. 1991 launches a campaign of extreme brutality against them, murdering and LRA Leader Joseph Kony IRIN The Sudanese government mutilating civilians, pillaging begins to provide direct villages, and abducting children to fill his ranks. support to the LRA. In return, the LRA supports 1993-4 Khartoum’s war against the Sudan People’s Liberation IRIN Army in southern Sudan. SPLA Rebels in Southern Sudan 1996 The U.S. government Protected village in northern Uganda places the LRA Stating its intent to prevent looting and abductions by the on a list of terrorist LRA, the Ugandan government forces more than two million organizations. -

PRESS RELEASE Nairobi 16Th February 2016, for Immediate Release Contact: Njonjo Mue, Senior Advisor KPTJ [email protected] 07

PRESS RELEASE Nairobi 16th February 2016, for immediate release Contact: Njonjo Mue, Senior Advisor KPTJ [email protected] 0721308911 Kenyan Civil Society concerned about the diminishing Democratic Space in Uganda ahead of the February 2016 Elections. On Monday, 15 February 2016, Uganda’s police arrested Dr. Kizza Besigye, the presidential flag bearer for the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). Dr. Besigye is one of the eight presidential candidates cleared to contest for the Presidency in the upcoming General Election scheduled for 18 February 2016. Dr. Besigye’s arrest came only three days to the election polling day and two days ahead of the official closing of the campaign period for political parties. The information we have is that Dr. Besigye was arrested on his way to a campaign rally at Makerere University where his supporters had gathered. During his arrest police lobbed tear gas and water cannons at the peaceful supporters to disperse them. This provoked the crowd leading to commotion between the supporters and the security agencies, resulting in the death of one of the supporters, with many others sustaining injuries. The arrest and detention of Dr. Besigye which also led to a disruption of his political campaign, was a violation of the universal right of peaceful assembly, freedom of expression and freedom of association guaranteed by Articles, 19, 22 and 23 of International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Articles 19, 20 and 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and Articles 9-11 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights to which Uganda is a party.