Democracy Or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: the U.S

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Lauren Ploch Analyst in African Affairs November 3, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41473 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Summary The United States government has implemented a range of programs to counter violent extremist threats in East Africa in response to Al Qaeda’s bombing of the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998 and subsequent transnational terrorist activity in the region. These programs include regional and bilateral efforts, both military and civilian. The programs seek to build regional intelligence, military, law enforcement, and judicial capacities; strengthen aviation, port, and border security; stem the flow of terrorist financing; and counter the spread of extremist ideologies. Current U.S.-led regional counterterrorism efforts include the State Department’s East Africa Regional Strategic Initiative (EARSI) and the U.S. military’s Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), part of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM). The United States has also provided significant assistance in support of the African Union’s (AU) peace operations in Somalia, where the country’s nascent security forces and AU peacekeepers face a complex insurgency waged by, among others, Al Shabaab, a local group linked to Al Qaeda that often resorts to terrorist tactics. The State Department reports that both Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab pose serious terrorist threats to the United States and U.S. interests in the region. Evidence of linkages between Al Shabaab and Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen, highlight another regional dimension of the threat posed by violent extremists in the area. -

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons Or Profiteers?

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons or Profiteers? By Jo-Ansie van Wyk Occasional Paper Series: Volume 2, Number 1, 2007 The Occasional Paper Series is published by The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. Views expressed in this Occasional Paper are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this Occassional Paper contains. Copyright © ACCORD 2007 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1608-3954 Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted to: The Editor, Occasional Paper Series, c/o ACCORD, Private Bag X018, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, Durban, South Africa or email: [email protected] Manuscripts should be about 10 000 words in length. All references must be included. Abstract It is easy to experience a sense of déjà vu when analysing political lead- ership in Africa. The perception is that African leaders rule failed states that have acquired tags such as “corruptocracies”, “chaosocracies” or “terrorocracies”. Perspectives on political leadership in Africa vary from the “criminalisation” of the state to political leadership as “dispensing patrimony”, the “recycling” of elites and the use of state power and resources to consolidate political and economic power. -

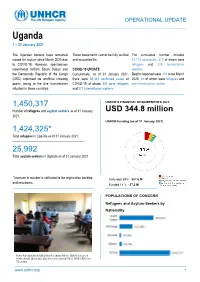

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations. -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

Uganda-A-Digital-Rights-View-Of-The

echnology and in Uganda A Digital Rights View of the January 2021 General Elections Policy Brief December 2020 VOTE Technology and Elections in Uganda Introduction As Uganda heads to presidential and parliamentary elections in January 2021, digital communications have taken centre-stage and are playing a crucial role in how candidates and parties engage with citizens. The country's electoral body decreed in June 2020 that, due to social distancing required by COVID-19 standard operating procedures, no physical campaigns would take place so as to ensure a healthy and safe environment for all stakeholders.1 Further, Parliament passed the Political Parties and Organisations (Conduct of Meetings and Elections) Regulations 2020,2 which aim to safeguard public health and safety of political party activities in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and, under regulation 5, provide for holding of political meetings through virtual means. The maximum number of persons allowed to attend campaign meetings was later set at 70 and then raised to 200.3 The use of the internet and related technologies is growing steadily in Uganda with 18.9 million subscribers, or 46 internet connections for every 100 Ugandans.4 However, radio remains the most widely accessible and usable technology with a penetration of 45%, compared to television at 17%, and computers at 4%.5 For the majority of Ugandans, the internet remains out of reach, particularly in rural areas where 75.5% of Ugandans live. The current election guidelines mean that any election process that runs predominantly on the back of technology and minimal physical organising and interaction is wont to come upon considerable challenges. -

Rwanda's Paul Kagame Talks Tough at Yale Despite Human Rights Protests | Africanews

10/28/2016 Rwanda's Paul Kagame talks tough at Yale despite human rights protests | Africanews Skip to main content Welcome to Africanews Please select your experience Rwanda's Paul Kagame talks tough at Yale despite human rights protests Abdur Rahman Alfa Shaban 21/09 - 00:31 Rwanda Rwandan president Paul Kagame delivered a lecture at the Yale University despite calls by rights group Human Rights Watch (HRW) for protests against his human rights record. Kagame was invited by the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale to deliver the 2016 annual Coca-Cola World Fund Lecture on Tuesday, September 20. Ahead of his lecture, HRW and other activists slammed Yale university for honouring a dictator and someone who according to them presided over a police state. Some participants in the international system tend to see this shift as a challenge to their historical leadership They continue to assert the right to define objectives and impose outcomes without consultation with those concerned. Kenneth Roth Follow @KenRoth As @Yale honors mass murderer Kagame, ask about the 30K+ he ordered killed, his Congo slaughter, his police state. bit.ly/2d2o9Wt 2:41 PM - 20 Sep 2016 105 66 Uwayezu j.deDieu Follow @Uwayezujd Huge mistake for #Yale to honor Paul #Kagame. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty have documented his history of human rights abuses. Shame on us. 3:30 PM - 19 Sep 2016 http://www.africanews.com/2016/09/21/rwanda-s-paul-kagame-talks-tough-at-yale-despite-human-rights-protests/ 1/5 10/28/2016 Rwanda's Paul Kagame talks tough at Yale despite human rights protests | Africanews Kagame in his address spoke on flaws that international communities had, stating that ‘‘the bias toward cooperation and dialogue in the multilateral system offers an alternative to zero-sum power politics.’‘ He added that efforts by international communities in the resolution of crisis was not just ineffectual but they sometimes worsened problems that they were meant to address in the first place. -

Museveni and No-Party Democracy in Uganda

1 Working Paper no.73 ‘POPULISM’ VISITS AFRICA: THE CASE OF YOWERI MUSEVENI AND NO-PARTY DEMOCRACY IN UGANDA Giovanni Carbone Università degli Studi di Milano December 2005 Copyright © Giovanni Carbone, 2005 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Research Centre ‘Populism’ Visits Africa: The Case of Yoweri Museveni and No-Party Democracy in Uganda Giovanni Carbone Università degli Studi di Milano1 The widespread adoption of electoral politics in virtually all world regions during the last part of the twentieth century has been accompanied by the emergence, in a number of reformed countries, of a new form of leadership. As the political space was formally opened up and state leadership crucially came to depend on electoral appeals for social support, many would- be leaders decided to set themselves apart by contesting for power on the basis of a strong anti-political and anti-party discourse. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Adminstrative Law and Governance Project Kenya, Malawi and Uganda

LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN UGANDA By Rose Nakayi ADMINSTRATIVE LAW AND GOVERNANCE PROJECT KENYA, MALAWI AND UGANDA The researcher acknowledges the research assistance offered by James Nkuubi and Brian Kibirango 1 Contents I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT............................................................. 6 A. Local Governance in the Pre-Independence Period ........................................................................... 6 B. Rule Making, Public Participation and Accountability in Pre independence Uganda ....................... 10 C. The Post-Independence Period........................................................................................................ 11 D. Post 1986 Period ............................................................................................................................ 12 III. LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN THE POST 1995 CONSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL REGIME ...... 12 A. Local Governance Under the 1995 Constitution and the Local Governments Act ................................ 12 B. Kampala Capital City: A Unique Position........................................................................................... 14 C. Public Participation in Rule Making in Local Governments and KCCA .............................................. 19 IV. ADJUDICATION OF DISPUTES AND IMPACT OF JUDICIAL REVIEW ................................. 24 D. Adjudication -

Leadership Turnovers in Sub-Saharan Africa

Analysis No. 192, August 2013 LEADERSHIP TURNOVERS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: FROM VIOLENCE AND COUPS TO PEACEFUL ELECTIONS? Giovanni Carbone Many African countries replaced their military or single-party regimes with pluralist politics during the early 1990s. This led to the introduction and regularisation of multiparty elections for the selection of a country’s president or prime minister. Of course, in many places, elections were not enough to start genuine democratization processes, as non-democratic rulers rapidly learned how to manipulate the vote and survive in the new political environment. Yet empirical evidence from our new “Leadership change” dataset – covering all 49 sub-Saharan states since 1960 (or subsequent year of independence) to 2012 – shows that elections did alter quite profoundly the way ordinary Africans can influence the selection and ousting of their leaders. Coups are now a rarer phenomenon, leadership turnovers have become more frequent, and peaceful alternation in power through the ballot box, if still uncommon, is part of a new political landscape. Giovanni Carbone, Associate Professor of Political Science, Università degli Studi di Milano ©ISPI2013 1 The opinions expressed herein are strictly personal and do not necessarily reflect the position of ISPI. The ISPI online papers are also published with the support of Cariplo The Arab Spring protests brought to the fore, once again, the issue of how to oust immovable authoritarian leaders. Tunisia’s Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali had been in power for 24 years. Hosni Mubarak ruled Egypt for 30 years. Muhammar Ghaddafi reigned over Libya for 42 years, while Syrians are still to see the end of the 43-year long rule of the al-Assad family. -

Report on the Uganda 2006 Elections Media Coverage

REPORT ON THE UGANDA 2006 ELECTIONS MEDIA COVERAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................2 MEDIA LANDSCAPE.............................................................................................2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK .........................................................................................2 PRESS FREEDOM ..................................................................................................3 METHODOLOGY...................................................................................................4 GENERAL COVERAGE OF THE PRESIDENTIAL CADIDATES...................5 STATE OWNED PRINT MEDIA: SPACE AND QUOTATION ...................................5 STATE OWNED PRINT MEDIA: BIAS AND PORTRAYAL......................................6 STATE OWNED PRINT MEDIA: THE AGENDA OF THE CANDIDATES.......7 STATE OWNED ELECTRONIC MEDIA: TIME AND QUOTATION.........................7 STATE OWNED ELECTRONIC MEDIA: BIAS AND PORTRAYAL.........................8 STATE OWNED ELECTRONIC MEDIA: THE AGENDA OF THE CANDIDATES.......................................................................................................9 HOW TO READ THE CHARTS ..........................................................................10 ANNEX I - ACRONYMS.......................................................................................11 ANNEX II - PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION RESULTS.......................................12 ANNEX III - A BRIEF HISTORICAL BACKGROUND -

Conclusion: an End to Conflict

Conclusion: an end to conflict Looking back on their daily lives over the last 40 years or so, the majority of Uganda's citizens will reflect on the turbulence of the times they have lived through. In some respects, there has been little change in the patterns of daily life for millions of Ugandans. People continue to cultivate the land by hand, or to herd their animals in ways that have barely altered since Uganda was created a hundred years ago. They continue to provide for their own subsistence, with relatively little contact with external markets. This sense of continuity was captured by Lorochom, the Karimojong elder, who explained, 'Governments change and the weather changes... but we continue herding our animals.' There have been some positive changes, however. The mismanagement of Uganda's economy under the regimes of Idi Amin and Obote II left Uganda amongst the poorest countries in the world. Improved management of the national economy has been one of the great achievements of the NRM and, provided that • Margaret Muhindo in her aid flows do not significantly diminish, Ugandans can kitchen garden. In a good reasonably look forward to continued economic growth, better public year, she will be able to sell surplus vegetables for cash. services, and further investments in essential infrastructure. In a bad year, she and her Nonetheless, turbulence has been the defining feature of the age, family will scrape by on the and it is in the political realm that turbulence has been profoundly food they grow. destructive. Instead of protecting the lives and property of its citizens, the state in one form or other has been responsible for the murder, torture, harassment, displacement, and impoverishment of its people.