Uganda: Recent Elections and Current Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

The Applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye Filled This Application by Notice of Motion Under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution Of

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA CRIMINAL APPLICATION NO. 83 OF 2016 (ARISING FROM MOR-OO-CR-AA-016/2016 AND NAK-A-NO.14/2016) COL (RTD) DR. KIZZA BESIGYE:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: APPLICANT VERSUS UGANDA::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: RESPONDENT. BEFORE: HON JUSTICE MR. MASALU MUSENE RULING The applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye filled this application by Notice of Motion under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution of Uganda, section 14 of the Trial on Indictments Act, cap 23 and rule 2 of the Judicature (criminal procedure)(applications rules S.I 13 -8) and all applicable laws. It is an application for bail pending trial. The applicant was represented by Mr. Ernest Kalibala together with Mr. Frederick Mpaga while the state was represented by M/S Florence Akello, principal state attorney and Mr. Brian Kalinaki also principal state attorney from the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The grounds in support of the application are outlined in the affidavit of the applicant, Col (Rtd) Kizza Besigye of Buyinja Zone, Nangabo sub-county, Kasangati in Wakiso district. In summary, they are as follows; 1. That on 13th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates Court of Moroto at Moroto and remanded in custody. 1 2. That on 18th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates court of Nakawa at Nakawa and remanded in custody. 3. That the applicant is a 60 year old responsible and respectable citizen of Uganda, a retired colonel in the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces and former presidential candidate in the 2016 presidential elections where he represented the Forum for Democratic Change, a dully registered political party. -

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: the U.S

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Lauren Ploch Analyst in African Affairs November 3, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41473 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Summary The United States government has implemented a range of programs to counter violent extremist threats in East Africa in response to Al Qaeda’s bombing of the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998 and subsequent transnational terrorist activity in the region. These programs include regional and bilateral efforts, both military and civilian. The programs seek to build regional intelligence, military, law enforcement, and judicial capacities; strengthen aviation, port, and border security; stem the flow of terrorist financing; and counter the spread of extremist ideologies. Current U.S.-led regional counterterrorism efforts include the State Department’s East Africa Regional Strategic Initiative (EARSI) and the U.S. military’s Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), part of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM). The United States has also provided significant assistance in support of the African Union’s (AU) peace operations in Somalia, where the country’s nascent security forces and AU peacekeepers face a complex insurgency waged by, among others, Al Shabaab, a local group linked to Al Qaeda that often resorts to terrorist tactics. The State Department reports that both Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab pose serious terrorist threats to the United States and U.S. interests in the region. Evidence of linkages between Al Shabaab and Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen, highlight another regional dimension of the threat posed by violent extremists in the area. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons Or Profiteers?

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons or Profiteers? By Jo-Ansie van Wyk Occasional Paper Series: Volume 2, Number 1, 2007 The Occasional Paper Series is published by The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. Views expressed in this Occasional Paper are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this Occassional Paper contains. Copyright © ACCORD 2007 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1608-3954 Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted to: The Editor, Occasional Paper Series, c/o ACCORD, Private Bag X018, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, Durban, South Africa or email: [email protected] Manuscripts should be about 10 000 words in length. All references must be included. Abstract It is easy to experience a sense of déjà vu when analysing political lead- ership in Africa. The perception is that African leaders rule failed states that have acquired tags such as “corruptocracies”, “chaosocracies” or “terrorocracies”. Perspectives on political leadership in Africa vary from the “criminalisation” of the state to political leadership as “dispensing patrimony”, the “recycling” of elites and the use of state power and resources to consolidate political and economic power. -

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

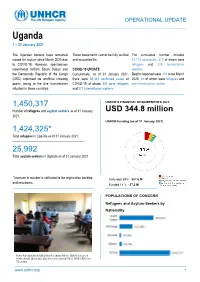

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations. -

Rwanda's Paul Kagame Talks Tough at Yale Despite Human Rights Protests | Africanews

10/28/2016 Rwanda's Paul Kagame talks tough at Yale despite human rights protests | Africanews Skip to main content Welcome to Africanews Please select your experience Rwanda's Paul Kagame talks tough at Yale despite human rights protests Abdur Rahman Alfa Shaban 21/09 - 00:31 Rwanda Rwandan president Paul Kagame delivered a lecture at the Yale University despite calls by rights group Human Rights Watch (HRW) for protests against his human rights record. Kagame was invited by the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale to deliver the 2016 annual Coca-Cola World Fund Lecture on Tuesday, September 20. Ahead of his lecture, HRW and other activists slammed Yale university for honouring a dictator and someone who according to them presided over a police state. Some participants in the international system tend to see this shift as a challenge to their historical leadership They continue to assert the right to define objectives and impose outcomes without consultation with those concerned. Kenneth Roth Follow @KenRoth As @Yale honors mass murderer Kagame, ask about the 30K+ he ordered killed, his Congo slaughter, his police state. bit.ly/2d2o9Wt 2:41 PM - 20 Sep 2016 105 66 Uwayezu j.deDieu Follow @Uwayezujd Huge mistake for #Yale to honor Paul #Kagame. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty have documented his history of human rights abuses. Shame on us. 3:30 PM - 19 Sep 2016 http://www.africanews.com/2016/09/21/rwanda-s-paul-kagame-talks-tough-at-yale-despite-human-rights-protests/ 1/5 10/28/2016 Rwanda's Paul Kagame talks tough at Yale despite human rights protests | Africanews Kagame in his address spoke on flaws that international communities had, stating that ‘‘the bias toward cooperation and dialogue in the multilateral system offers an alternative to zero-sum power politics.’‘ He added that efforts by international communities in the resolution of crisis was not just ineffectual but they sometimes worsened problems that they were meant to address in the first place. -

Museveni and No-Party Democracy in Uganda

1 Working Paper no.73 ‘POPULISM’ VISITS AFRICA: THE CASE OF YOWERI MUSEVENI AND NO-PARTY DEMOCRACY IN UGANDA Giovanni Carbone Università degli Studi di Milano December 2005 Copyright © Giovanni Carbone, 2005 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Research Centre ‘Populism’ Visits Africa: The Case of Yoweri Museveni and No-Party Democracy in Uganda Giovanni Carbone Università degli Studi di Milano1 The widespread adoption of electoral politics in virtually all world regions during the last part of the twentieth century has been accompanied by the emergence, in a number of reformed countries, of a new form of leadership. As the political space was formally opened up and state leadership crucially came to depend on electoral appeals for social support, many would- be leaders decided to set themselves apart by contesting for power on the basis of a strong anti-political and anti-party discourse. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Leadership Turnovers in Sub-Saharan Africa

Analysis No. 192, August 2013 LEADERSHIP TURNOVERS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: FROM VIOLENCE AND COUPS TO PEACEFUL ELECTIONS? Giovanni Carbone Many African countries replaced their military or single-party regimes with pluralist politics during the early 1990s. This led to the introduction and regularisation of multiparty elections for the selection of a country’s president or prime minister. Of course, in many places, elections were not enough to start genuine democratization processes, as non-democratic rulers rapidly learned how to manipulate the vote and survive in the new political environment. Yet empirical evidence from our new “Leadership change” dataset – covering all 49 sub-Saharan states since 1960 (or subsequent year of independence) to 2012 – shows that elections did alter quite profoundly the way ordinary Africans can influence the selection and ousting of their leaders. Coups are now a rarer phenomenon, leadership turnovers have become more frequent, and peaceful alternation in power through the ballot box, if still uncommon, is part of a new political landscape. Giovanni Carbone, Associate Professor of Political Science, Università degli Studi di Milano ©ISPI2013 1 The opinions expressed herein are strictly personal and do not necessarily reflect the position of ISPI. The ISPI online papers are also published with the support of Cariplo The Arab Spring protests brought to the fore, once again, the issue of how to oust immovable authoritarian leaders. Tunisia’s Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali had been in power for 24 years. Hosni Mubarak ruled Egypt for 30 years. Muhammar Ghaddafi reigned over Libya for 42 years, while Syrians are still to see the end of the 43-year long rule of the al-Assad family. -

Conclusion: an End to Conflict

Conclusion: an end to conflict Looking back on their daily lives over the last 40 years or so, the majority of Uganda's citizens will reflect on the turbulence of the times they have lived through. In some respects, there has been little change in the patterns of daily life for millions of Ugandans. People continue to cultivate the land by hand, or to herd their animals in ways that have barely altered since Uganda was created a hundred years ago. They continue to provide for their own subsistence, with relatively little contact with external markets. This sense of continuity was captured by Lorochom, the Karimojong elder, who explained, 'Governments change and the weather changes... but we continue herding our animals.' There have been some positive changes, however. The mismanagement of Uganda's economy under the regimes of Idi Amin and Obote II left Uganda amongst the poorest countries in the world. Improved management of the national economy has been one of the great achievements of the NRM and, provided that • Margaret Muhindo in her aid flows do not significantly diminish, Ugandans can kitchen garden. In a good reasonably look forward to continued economic growth, better public year, she will be able to sell surplus vegetables for cash. services, and further investments in essential infrastructure. In a bad year, she and her Nonetheless, turbulence has been the defining feature of the age, family will scrape by on the and it is in the political realm that turbulence has been profoundly food they grow. destructive. Instead of protecting the lives and property of its citizens, the state in one form or other has been responsible for the murder, torture, harassment, displacement, and impoverishment of its people. -

Democracy Or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda

Journal of African Democracy and Development Vol. 1, Issue 2, 2017, 109-127, www.kas.de/Uganda/en/ Democracy or Fallacy: Discourses Shaping Multi-Party Politics and Development in Uganda Jacqueline Adongo Masengoa Abstract This paper examines the discourses shaping the introduction of multi-party politics in Uganda and how it is linked to democracy and development. The paper shows that most Ugandans prefer multi-party politics because they link it to democracy and development. This is why when the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M) captured power in 1986 and multi-party politics was abolished, there was pressure from the public to reinstate it through the 2005 referendum in which the people voted in favour of a multi- party system. The paper also examines the role played by Ugandan politicians and professional middle class such as writers and literary critics (local agency) in the return of multi-party politics in Uganda. It explores their contribution of in re-democratising the Ugandan state and argues that despite the common belief that multi-party politics aids democracy and development, it might not be the case in Uganda. Multi-party politics in Uganda has turned out not to necessarily mean democracy, and eventually development. The paper grapples with the question of what democracy is in Uganda and/ or to Ugandans, and the extent to which the Ugandan political arena can be considered democratic, and as a fertile ground for development. Did the return to multi- party politics in Uganda guarantee democracy or is it just a fallacy? What is the relationship between democracy and development in Uganda? Keywords: Multi-party politics, democracy, Fallacy, Uganda 1.