State Surveillance in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Towards Sustainable Peace in Uganda?

TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE PEACE IN UGANDA? - a study of peacebuilding in northern Uganda and the involvement of the civil society during the LRA/ government of Uganda peace process of 2006-2007 Anna Svenson Spring term of 2007 Master thesis Political Sciences, POM 556 Supervisor: Emil Uddhammar TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................... 7 PART I – INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT AND METHODOLOGICAL DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................... 8 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 9 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Purpose and research questions...................................................................................... 10 1.3 Limitations ..................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Disposition ..................................................................................................................... 11 2. METHODOLOGICAL DISCUSSION ............................................................................ 13 2.1 The project – choice and -

Ouganda : Un Pays En Mutation Au Cœur D’Une Zone De Fractures

Les Études du CERI N 4 - septembre 1995 Ouganda : un pays en mutation au cœur d’une zone de fractures Richard Banégas Centre d’études et de recherches internationales Fondation nationale des sciences politiques Ouganda : un pays en mutation au cœur d’une zone de fractures Richard Banégas Entre les images de mort des années Amin et Obote, de la guerre civile et du sida et le souvenir nostalgique de la “ perle de l’Afrique ” (Churchill), l’Ouganda reste prisonnier de clichés hérités d’un passé chaotique qui ne reflètent pourtant plus guère la réalité. L’Ou- ganda actuel est en effet un pays en complète mutation, en pleine reconstruction économique et politique, qui devient un pôle essentiel de stabilité régionale au coeur d’une zone de fractures minée par la violence, marquée par des conflits “ tectoniques ” et la déliquescence des structures économiques ou étatiques. Après des années de guerre civile, au gré d’un processus de pacification et de démocratisation assez lent, un nouvel ordre politique est en train d’émerger. Au plan économique, en contraste avec ses voisins immédiats, l’Ou- ganda offre l’image d’un pays en croissance qui offre aux investisseurs des opportunités d’autant plus intéressantes que se réactive un processus d’intégration régionale (au sein de la Communauté est-africaine) qui, à l’horizon 2000, devrait constituer un des plus vastes marchés d’Afrique avec près de 100 millions d’habitants. A travers cette étude, nous voudrions d’abord évaluer l’ampleur de ces mutations opé- rées par l’Ouganda depuis quelques années et les enjeux économiques, politiques et di- plomatiques qu’elles comportent pour l’ensemble de la zone. -

Elite Strategies and Contested Dominance in Kampala

ESID Working Paper No. 146 Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala Nansozi K. Muwanga1, Paul I. Mukwaya2 and Tom Goodfellow3 June 2020 1 Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected]. 3 Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield, UK Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-56-9 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala. Abstract Although Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) has dominated Uganda’s political scene for over three decades, the capital Kampala refuses to submit to the NRM’s grip. As opposition activism in the city has become increasingly explosive, the ruling elite has developed a widening range of strategies to try and win urban support and constrain opposition. In this paper, we subject the NRM’s strategies over the decade 2010-2020 to close scrutiny. We explore elite strategies pursued both from the ‘top down’, through legal and administrative manoeuvres and a ramping up of violent coercion, and from the ‘bottom up’, through attempts to build support among urban youth and infiltrate organisations in the urban informal transport sector. Although this evolving suite of strategies and tactics has met with some success in specific places and times, opposition has constantly resurfaced. -

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 490 | FEBRUARY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE w w w .usip.org North Korea in Africa: Historical Solidarity, China’s Role, and Sanctions Evasion By Benjamin R. Young Contents Introduction ...................................3 Historical Solidarity ......................4 The Role of China in North Korea’s Africa Policy .........7 Mutually Beneficial Relations and Shared Anti-Imperialism..... 10 Policy Recommendations .......... 13 The Unknown Soldier statue, constructed by North Korea, at the Heroes’ Acre memorial near Windhoek, Namibia. (Photo by Oliver Gerhard/Shutterstock) Summary • North Korea’s Africa policy is based African arms trade, construction of owing to African governments’ lax on historical linkages and mutually munitions factories, and illicit traf- sanctions enforcement and the beneficial relationships with African ficking of rhino horns and ivory. Kim family regime’s need for hard countries. Historical solidarity re- • China has been complicit in North currency. volving around anticolonialism and Korea’s illicit activities in Africa, es- • To curtail North Korea’s illicit activ- national self-reliance is an under- pecially in the construction and de- ity in Africa, Western governments emphasized facet of North Korea– velopment of Uganda’s largest arms should take into account the histor- Africa partnerships. manufacturer and in allowing the il- ical solidarity between North Korea • As a result, many African countries legal trade of ivory and rhino horns and Africa, work closely with the Af- continue to have close ties with to pass through Chinese networks. rican Union, seek cooperation with Pyongyang despite United Nations • For its part, North Korea looks to China, and undercut North Korean sanctions on North Korea. -

2016 Afsol Book.Pdf

African-Centred Solutions Building Peace and Security in Africa Editors Sunday Okello and Mesfin Gebremichael Copyright © 2016 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University Printed in Ethiopia First published: 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electoronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording or inclusion in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Institute for Peace and Security Studies. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. ISBN: 978-99944-943-3-0 Table of Contents Chapter One Introduction by Sunday Angoma Okello ................................................... 1 Chapter Two Interrogating the Concept and Ideal of African-Centred Solution to African Peace and Security Challenges By Amadu Sesay ..................... 21 Chapter Three Enriching the African-Centred Solutions Concept: Reflections on AU-led Peace Support Operations in Sudan and Somalia By Dawit Yohannes ....................................................................................................... 47 Chapter Four South Sudan: Exploring African–Centred Hybrid Sustainable Peacebuilding and Security By Evelyn Mayanja ................................... 75 Chapter Five Statehood, Small Arms and Security Governance in Southwest Ethiopia: The Need for an African-Centred Perspective By Mercy Fekadu Mulugeta ....................................................................................... 103 Chapter Six Understanding Peaceful Coexistence from an Urban Refugee Perspective in Africa: The Case of Uganda By Brenda Aleesi ............ 135 Chapter Seven Civil Society in Conflict Transformation: Key Evidence from Kenya’s Post-election Violence By Caleb Wafula ................................................. 161 Chapter Eight Boko Haram Insurgency and Sustainable Peace in Nigeria and the Lake Chad Region: AU-MNJTF’s Intervention By Naeke Sixtus Mougombe . -

The Applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye Filled This Application by Notice of Motion Under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution Of

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA CRIMINAL APPLICATION NO. 83 OF 2016 (ARISING FROM MOR-OO-CR-AA-016/2016 AND NAK-A-NO.14/2016) COL (RTD) DR. KIZZA BESIGYE:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: APPLICANT VERSUS UGANDA::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: RESPONDENT. BEFORE: HON JUSTICE MR. MASALU MUSENE RULING The applicant Col Rtd Dr. Kizza Besigye filled this application by Notice of Motion under Article 23 (6) of the Constitution of Uganda, section 14 of the Trial on Indictments Act, cap 23 and rule 2 of the Judicature (criminal procedure)(applications rules S.I 13 -8) and all applicable laws. It is an application for bail pending trial. The applicant was represented by Mr. Ernest Kalibala together with Mr. Frederick Mpaga while the state was represented by M/S Florence Akello, principal state attorney and Mr. Brian Kalinaki also principal state attorney from the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The grounds in support of the application are outlined in the affidavit of the applicant, Col (Rtd) Kizza Besigye of Buyinja Zone, Nangabo sub-county, Kasangati in Wakiso district. In summary, they are as follows; 1. That on 13th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates Court of Moroto at Moroto and remanded in custody. 1 2. That on 18th May 2016, the applicant was charged with the offence of treason in the Chief Magistrates court of Nakawa at Nakawa and remanded in custody. 3. That the applicant is a 60 year old responsible and respectable citizen of Uganda, a retired colonel in the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces and former presidential candidate in the 2016 presidential elections where he represented the Forum for Democratic Change, a dully registered political party. -

Read the Excerpt

Prologue he wins the decisive game, but she has no idea what it means. Nobody has told her what’s at stake, so she just plays, like she Salways does. She has no idea she has qualified to compete at the Olympiad. No idea what the Olympiad is. No idea that her qualifying means that in a few months she will fly to the city of Khanty-Mansiysk in remote central Russia. No idea where Russia even is. When she learns all of this, she asks only one question: “Is it cold there?” She travels to the Olympiad with nine teammates, all of them a decade older, in their twenties, and even though she has known many of them for a while and ljourneys by their side for 27 hours across the globe to Siberia, none of her teammates really have any idea where she is from or where she aspires to go, because Phiona Mutesi is from someplace where girls like her don’t talk about that. 19th sept. 2010 Dear mum, I went to the airport. I was very happy to go to the airport. this was only my second time to leave my home. When I riched to the airport I was some how scared because I was going to play the best chess players in the world. So I waved to my friends and my brothers. Some of them cried 1 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Crothers_i-viii_1-232_ptr_cj.indd 1 7/30/12 9:26 AM Prologue because they were going to miss me and I had to go. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

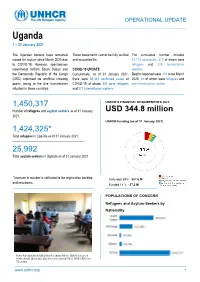

Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Uganda 1 – 31 January 2021 The Ugandan borders have remained These movements cannot be fully verified The cumulative number includes closed for asylum since March 2020 due and accounted for. 14,114 recoveries, 372 of whom were to COVID-19. However, spontaneuos refugees and 229 humanitarian movements to/from South Sudan and COVID-19 UPDATE workers. the Democratic Republic of the Congo Cumulatively, as of 31 January 2021, Deaths reported were 318 since March (DRC) continued via unofficial crossing there were 39,314 confirmed cases of 2020, six of whom were refugees and points, owing to the dire humanitarian COVID-19, of whom, 381 were refugees one humanitarian worker. situation in these countries. and 277 humanitarian workers. cannot be fully verified and accounted 1,450,317 UNHCR’S FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS 2021: Number of refugees and asylum seekers as of 31 January USD 344.8 million 2021. UNHCR Funding (as of 31 January 2021) 1,424,325* Total refugees in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. 25,992 Total asylum-seekers in Uganda as of 31 January 2021. *Increase in number is attributed to the registration backlog Unfunded 89% - 307.6 M and new-borns. Funded 11 % - 37.2 M POPULATIONS OF CONCERN Refugees and Asylum-Seekers by Nationality Senior four students at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district attend class after schools re-opened. Photo ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > UGANDA / 1 – 31 January 2021 A senior four candidate at Valley View Secondary School, Bidibidi settlement, Yumbe district, studies in preparation for his final examinations.