The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Primary Education in Uganda IOB Impact Evaluation IOB Impact Evaluation | No

IOB Impact Evaluation | no. 311 | April 2008 Primary Education in Uganda IOB Impact Evaluation | no. 311 | April 2008 | Primary Education in Uganda O S D R 6 6 2 4 / E www.minbuza.nl The Hague eb April 2008 ISBN 978 90 5328 361 5 www.minbuza.nl/iob-en Ministry of Foreign Affairs P.O. Box 20061 2500 The Netherlands evaluation studies published by the policy and operations evaluation department (IOB) 2000-2008 Evaluation studies published before 2000 can be found on the IOB-website: www.minbuza.nl/iob-en 284 2000 InstitutionalDevelopmentNetherlands support to the 301 2006 FromProjectAidtowardsSectorSupport water sector. An evaluation of the sector-wide approach in Dutch bilateral aid isbn 90-5328-274-2 1998–2005. isbn 90-5146-000-7 285 2000 OnderzoeknaardesamenwerkingtussenMalien 302 2006 EvaluatievanhetNederlandsemensenrechtenbeleid Nederland1994-1998 indeexternebetrekkingen isbn 90-5328-278-5 isbn 90-5328-350-1 286 2001 SmallholderDairySupportProgramme(SDSP)Tanzania 303 2006 DutchHumanitarianAssistance Inspection of its identification, formulation and tendering process An Evaluation isbn 90-5328-298-x isbn 90-5328-352-8 287 2001 DekunstvanhetInternationaalcultuurbeleid1997-2000 304 2007 EvaluatievandevernieuwingvanhetNederlandse isbn 90-5328-300-5 onderzoeksbeleid1992-2005 288 2002 Health,nutritionandpopulation isbn 978-90-5328-353-0 Burkina Faso Mozambique Yemen 304 2007 EvaluationoftheNetherlands'ResearchPolicy1992-2005 isbn 90-5328-301-3 (Summary) 289 2002 CultuurenOntwikkeling isbn 978-90-5328-353-0 De evaluatie van een beleidsthema -

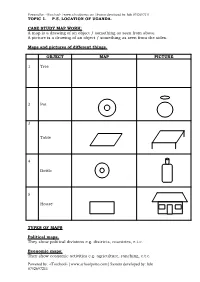

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Environmental Decentralization and the Management of Forest Resources in Masindi District, Uganda

ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE IN AFRICA WORKING PAPERS: WP #8 COMMERCE, KINGS AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN UGANDA: DECENTRALIZING NATURAL RESOURCES TO CONSOLIDATE THE CENTRAL STATE by Frank Emmanuel Muhereza Febuary 2003 EDITORS World Resources Institute Jesse C. Ribot and Jeremy Lind 10 G Street, NE COPY EDITOR Washington DC 20002 Florence Daviet www.wri.org ABSTRACT This study critically explores the decentralizing of forest management powers in Uganda in order to determine the extent to which significant discretionary powers have shifted to popularly elected and downwardly accountable local governments. Effective political or democratic decentralization depends on the transfer of local discretionary powers. However, in common with other states in Africa undergoing various types of “decentralization” reforms, state interests are of supreme importance in understanding forest-management reforms. The analysis centers on the transfer of powers to manage forests in Masindi District, an area rich in natural wealth located in western Uganda. The decentralization reforms in Masindi returns forests to unelected traditional authorities, as well as privatizes limited powers to manage forest resources to licensed user-groups. However, the Forest Department was interested in transferring only those powers that increased Forest Department revenues while reducing expenditures. Only limited powers to manage forests were transferred to democratically elected and downwardly accountable local governments. Actors in local government were left in an uncertain and weak bargaining position following the transfer of powers. While privatization resulted in higher Forest Department revenues, the tradeoff was greater involvement of private sector actors in the Department’s decision making. To the dismay of the Forest Department, in the process of consolidating their new powers, private-sector user groups were able to influence decision making up to the highest levels of the forestry sector. -

The History of Syphilis in Uganda

Bull. Org. mond. Santeh 1956, 15, 1041-1055 Bull. Wld Hith Org. THE HISTORY OF SYPHILIS IN UGANDA J. N. P. DAVIES, M.D., Ch.B., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. Professor of Pathology, Makerere College Medical School, Kampala, Uganda SYNOPSIS The circumstances of an alleged first outbreak of syphilis in Uganda in 1897 are examined and attention is drawn to certain features which render possible alternative explanations of the history of syphilis in that country. It is suggested that an endemic form of syphilis was an old disease of southern Uganda and that protective infantile inoculation was practised. The country came under the observation of European clinicians at a time when endemic syphilis was being replaced by true venereal syphilis. This process has now been completed, endemic syphilis has disappeared, and venereal syphilis is now widespread and a more serious problem than ever. This theory explains the observations of other writers and reconciles the apparent discrepancies between various reports. Until comparatively recent times the country now known as Uganda was cut off from the rest of the world. The Nile swamps to the north, the impenetrable Congo forest to the west, the mountains and the upland plateaux with the warrior Masai to the east, and the other immense difficul- ties of African travel, had protected the country from intrusion. In the southern lacustrine areas there had developed the remarkable indigenous kingdoms of Bunyoro and Buganda. These became conscious of the larger outside world about 1850, when a Baluch soldier from Zanzibar reached the court of the King of Buganda, the Kabaka Suna. -

JAF-F'ac FORUM D'action COMMLINE Offrce of the Chairman Bureau Du Presrdent

All'rcan Programnte tbr Onchocerclasts Control Prograrnme afircatn de luttc contre I'onchocercose JOINT ACTION FORUM JAF-F'AC FORUM D'ACTION COMMLINE Offrce of the Chairman Bureau du Presrdent JOINT ACTION FORUM JAI'5/INF/DOC.2 Frfth sessron ORIGINAL: ENGLISH The Hasue. 8-10 December 1999 September 1999 REPORT ON APOC/NOTF WORKSHOP ON REASSESSMENT OF THE 1998 INDEPENDENT MONITORING OF CDTI PROJECTS a A I?ITI CAN I'IIOG ITAI\{ i\,I E ITOIT ONCHOCE,RCIASIS CONTROL (APOC) RE,PORT ON APOC/NOTF WORKSHOP ON REASSESSMENT OF THtr 1998 INDEPENDENT MONITORING OF CDTI PROJECTS I t , K.\ l],,\ L [1, tr (;,\ \ l).{ 1\,1A \' 3-8, I ggg TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents I Acknowledgements ii List of Acronyms iii Executive Summary 1 Summary of Recommendations and Conclusions 2 Background to the Workshop 8 Opening 9 Objectives 1l Expected Outcomes t2 Special Plenary - Difference Between CBIT and CDTI 13 Session I - Community Involvement in CDTI/ Health Education 15 Session 2 - Training of CDDs l7 Session 3 - Recording and Reporting Procedures 18 Session 4 - Training Health Personnel on CDTI/Supervision 20 Session 5 - Reporting Treatment Coverage Rates 22 Session 6 - Community Support for CDDs: Incentives 24 Session 7 - Involvement of State/District Health Services 26 Special Session - Women's Participation in CDTI 29 Special Session - Other Matters 31 Closing Remarks JJ Appendices 1. Mobilisation Structure 34 2. Guidelines for Effective N{obilisation 35 3. Mectizan Treatment Register 37 4. Guide for Training and Retarining CDDs 38 5. Checklist for Trainers of Health Personnel 40 6. Checklist for Supervision of Health Personnel 4t 7. -

State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2

CONTENTS State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Methodology 5 3.0 Country Context 6 3.1 Political Economy 6 3.2 Political Enviroment 6 3.3 ICT Status 7 3.4 State Co-ownership of Network Operators and Infrastructure 8 3.5 Legal Protection of Human Rights 9 3.6 Status of ICT Legislation 11 4.0 Overview of Information Controls in Place 13 4.1 Content Controls in Legislation 13 4.1.1 Offensive Communication 14 4.1.2 Pornographic or Obscene Content 15 4.1.3 Hate Speech 16 4.1.4 Defamation 17 4.1.5 False Information “Fake news” 18 4.1.6 National Security and Terrorism 19 4.1.7 Censorship 20 4.1.8 Internet Shutdowns 21 4.1.8 Other Restrictions 22 5.0 Internet Intermediaries and Internet Freedom 23 5.1 Limitation of Liability on Intermediaries 23 5.2 Imposition of Liability on Intermediaries 24 5.3 Restrictions Imposed by Intermediaries 26 5.4 Violation of Privacy Rights 28 5.4.1 Processing and Disclosure of Personal Information 28 5.4.2 Retention of Content Data 29 5.4.3 Surveillance and Interception of Communication 30 5.4.4 Poor Accountability of Intermediaries 32 5.5 Inadequate Complaint Handling Frameworks and Remedies 33 5.6 Pushbacks Against Violations and the Promotion of Rights 34 6.0 Conclusion and Recommendations 36 6.1 Conclusion 36 6.2 Recommendations 37 6.2.1 Government 37 6.2.2 Intermediaries 38 6.3.3 Media 38 6.3.4 Academia 38 6.3.5 Technical Community 39 6.3.6 Civil Society 39 6.3.7 Public 39 3 State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 1.0 Introduction Growing use of the internet and related technologies has provided new spaces for advancing the right to freedom of expression (FOE), promoted access to information, and spurred innovation and socio-economic growth in various African countries. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of January 2017

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY 2017 Issue Date: 6th February 2017 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. National Overview Tension continues to rise in the Rwenzori sub region following the re-arrest of the King (Omusinga) Charles Wesley Mumbere of the Rwenzururu Kingdom (Obusinga Bwa Rwenzururu). He had been arrested in December 2016 on charges related to terrorism, aggravated robbery and attempted murder.1 These charges stemmed from attacks on police officers and police installations in the region in the last couple of months. King Mumbere was re-arrested just hours after Jinja High Court released him on bail. Prior to the re- arrest, one of the bail conditions was that he should not go to his Kingdom. The re-arrest of the King has not gone down well with some sections of his Kingdom. Area Members of the Parliament have condemned the re-arrest saying it was betrayal of the entire kingdom by the President of Uganda, and that the re-arrest was unlawful.2 However Police say King Mumbere was re-arrested because the latest investigations discovered other charges which he individually committed during the clashes in the region.3 The re-arrest of the King has the possibility of worsening the already precarious situation. In the last three years, more than three hundred (300) people have been killed, military installations attacked, houses, property and domestic livestock destroyed and many people injured in a conflict that is multidimensional. -

Are Family Planning Programs Reaching the Disadvantaged? an Equity Case Study of Uganda

POLICY Brief September 2020 Are Family Planning Programs Reaching Authors: Kaja Jurczynska, the Disadvantaged? Kevin Ward, Lyubov Teplitskaya, Shiza Farid, and Kristin Bietsch An Equity Case Study of Uganda Introduction In just over a decade, the share of married women using modern methods of contraception in Uganda nearly doubled, increasing Equity in health means that from 18 percent in 2006 to 35 percent in 2016, and to a further 37 everyone has a fair opportunity 1 percent in 2019 (UBOS and ICF, 2018; FP2020, 2020). Uganda to reach their health potential, has cemented its commitment to family planning through the regardless of wealth, education, country’s first Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan for sex, age, race or ethnic group, 2015–2020 and subsequent pledges under the Family Planning residence, disability, and other 2020 (FP2020) partnership. Among its goals, Uganda has status or social group. committed to reducing inequities, particularly for those living in rural areas, adolescents, and those facing financial hardship (Ministry of Health, 2014; FP2020, 2017). Despite this progress, Uganda has experienced challenges in Box 1. HP’s Approach for meeting its family planning commitments for 2020 and 2021, Diagnosing Inequity in including those that are equity focused. For example, unmet Family Planning Programs need is higher than desired, at one quarter of all married women compared to the goal of 10 percent by 2020. The use of modern The approach answers the “who, contraceptive methods lags behind the 2020 goal of 50 percent what, and where” of inequities in (FP2020, 2019). While inadequate funding of family planning family planning: activities remains a key barrier to progress (Wanyana et al., 2019), better directing information and services for those women who • Who is experiencing inequity? need them most could address longstanding inequities while also • What components of bolstering uptake and improving allocative efficiency. -

The Extent and Nature of Multidimensional Child Poverty and Deprivation the Extent and Nature of Multidimensional Child Poverty and Deprivation

MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION IN UGANDA: VOLUME 1 THE EXTENT AND NATURE OF MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION THE EXTENT AND NATURE OF MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION MARCH 2019 MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION IN UGANDA: VOLUME 1 THE EXTENT AND NATURE OF MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research and drafting of this report was led by David Gordon, Şebnem Eroğlu, Eldin Fahmy, Viliami Konifelenisi Fifita, Shailen Nandy, Acomo Oloya, Marco Pomati and Helen Anderson from the University of Bristol and the University of Cardiff, in close collaboration with the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and UNICEF Uganda. This pioneering work to better understand multidimensional child poverty and deprivation in Uganda would not have been possible without the vision, oversight and support of James Muwonge, Vincent Ssennono, Bylon Twesigye and Stephen Baryahirwa from UBOS, and Diego Angemi, Sarah Kabaija, Arthur Muteesasira and Amna Silim from UNICEF Uganda. Frances Ellery provided significant editorial inputs, while Rachel Kanyana designed the report. Above all, we are very grateful to all enumerators, field researchers and participants who volunteered their time to take part in the UNHS 2016/17 and focus group discussions. We hope these reports do justice to their contributions. I MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION IN UGANDA VOLUME 1: THE EXTENT AND NATURE OF MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHILD POVERTY AND DEPRIVATION FOREWORD As enshrined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, children have the right to an adequate standard of living, and to be free from any form of health, education, nutrition, care or protection related deprivation. -

Stereotypes As Sources of Conflict in Uganda

Stereotypes as Sources of Conflict in Uganda Justus NIL, gaju Editorial Consultant/BMG Wordsmith, Kampala Email: ibmugâ;u ;a yahoo.co.uk In order- to govern, colonial authorities had frequently found it expedient to divide in order to rule. An example of such a situation was, for instance, the dividing up of Uganda into a society of contradictory and mutually suspicious interests. They made, for instance, the central area of the country, and to some extent, areas in the east, produce cash crops for export. In so doing they made one part of Uganda produce cash crops and another reservoir of cheap labour and of recruitment into the colonial army. This had the inevitability of producing inequalities, which in turn generated intense and disruptive conflicts between the different ethnic groups involved. The rivalry over access to opportunities gave rise to the formation of attitudes of superiority and inferiority complexes. President Yoweri Museveni (MISR, 1987:20) The history of modern Uganda is a long story of stereotyping. From the beginning of colonial rule to the present, the history of Uganda has been reconstructed in neat- looking but deceptive stereotypes. These stereotypes can be summed up as follows: aliens and natives, centralised/developed/sophisticated states versus primitive stateless societies, the oppressor and the oppressed, the developed north and the backward north, the rulers and subjects, and the monarchists/traditionalists and the republicans. Uganda's history has also been reconstructed in terms of the "modermsers" versus the "Luddites", patriots against quislings, heroes/martyrs and villains, the self-serving elite and the long-suffering oppressed/exploited masses, the "swine" versus the visionary leaders, the spineless politicians and the blue-eyed revolutionaries, etc.