Primary Education in Uganda IOB Impact Evaluation IOB Impact Evaluation | No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

JAF-F'ac FORUM D'action COMMLINE Offrce of the Chairman Bureau Du Presrdent

All'rcan Programnte tbr Onchocerclasts Control Prograrnme afircatn de luttc contre I'onchocercose JOINT ACTION FORUM JAF-F'AC FORUM D'ACTION COMMLINE Offrce of the Chairman Bureau du Presrdent JOINT ACTION FORUM JAI'5/INF/DOC.2 Frfth sessron ORIGINAL: ENGLISH The Hasue. 8-10 December 1999 September 1999 REPORT ON APOC/NOTF WORKSHOP ON REASSESSMENT OF THE 1998 INDEPENDENT MONITORING OF CDTI PROJECTS a A I?ITI CAN I'IIOG ITAI\{ i\,I E ITOIT ONCHOCE,RCIASIS CONTROL (APOC) RE,PORT ON APOC/NOTF WORKSHOP ON REASSESSMENT OF THtr 1998 INDEPENDENT MONITORING OF CDTI PROJECTS I t , K.\ l],,\ L [1, tr (;,\ \ l).{ 1\,1A \' 3-8, I ggg TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents I Acknowledgements ii List of Acronyms iii Executive Summary 1 Summary of Recommendations and Conclusions 2 Background to the Workshop 8 Opening 9 Objectives 1l Expected Outcomes t2 Special Plenary - Difference Between CBIT and CDTI 13 Session I - Community Involvement in CDTI/ Health Education 15 Session 2 - Training of CDDs l7 Session 3 - Recording and Reporting Procedures 18 Session 4 - Training Health Personnel on CDTI/Supervision 20 Session 5 - Reporting Treatment Coverage Rates 22 Session 6 - Community Support for CDDs: Incentives 24 Session 7 - Involvement of State/District Health Services 26 Special Session - Women's Participation in CDTI 29 Special Session - Other Matters 31 Closing Remarks JJ Appendices 1. Mobilisation Structure 34 2. Guidelines for Effective N{obilisation 35 3. Mectizan Treatment Register 37 4. Guide for Training and Retarining CDDs 38 5. Checklist for Trainers of Health Personnel 40 6. Checklist for Supervision of Health Personnel 4t 7. -

Uganda and Post-Conflict Recovery: 1987 (A)

Uganda and Post-Conflict Recovery: 1987 (A) Francis Unyofu sat back in his office chair and stared at the dilapidated ceiling. He had not thought life in the government would be quite like this. But fifteen years of political and economic chaos could not be erased in just one year. And there were certainly higher priorities than renovating this government office. At least there was peace now -- well, in most parts of the country -- so Uganda could try to return to some form of normalcy. At independence in October 1962 there was little indication that Uganda was headed for such privations. Independence came without a struggle: the British set a timetable for their withdrawal and stuck to it. In Uganda it was the Ugandans, not the Europeans, who grew the cotton and coffee that brought a higher living standard, financed the education of their children, and led to increased expectations for the future. There was an impressive number of educated and prosperous middle-class professionals, the prestigious national Makere University, and a gleaming new teaching hospital at Mulago. At independence, Uganda looked optimistically at the future. Now, 25 years later, it is just looking to rebuild. It is January 1987, one year after Yoweri Museveni led the National Resistance Army (NRA) to power. The past year was spent bringing an inclusive coalition together and debating the country's economic and political future. These were exciting times in the capital, Kampala. But the time for debate is past. The people are getting edgy: there are long queues for consumer goods, unemployment is so high it is not even counted and many factories are not operating. -

UGANDA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

UGANDA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 20 April 2011 UGANDA DATE Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN UGANDA FROM 3 FEBRUARY TO 20 APRIL 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON UGANDA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 3 FEBRUARY AND 20 APRIL 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Political developments: 1962 – early 2011 ......................................................... 3.01 Conflict with Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): 1986 to 2010.............................. 3.07 Amnesty for rebels (Including LRA combatants) .............................................. 3.09 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Kampala bombings July 2010 ............................................................................. 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION.......................................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .................................................................................................. -

Africa Confidential

www.africa-confidential.com 4 April 2003 Vol 44 No 7 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL UGANDA/RWANDA 2 UGANDA Soccer war, Congo war In the phoney war, the score was The great U-turn nil-nil as Rwanda and Uganda President Museveni calls for the freeing of parties and the chance of played a qualifier in Africa’s Cup of a third term at the top Nations soccer tournament last It was the sharpest of U-turns. President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, who has vehemently defended his weekend in Kigali. In the real war in eastern Congo-Kinshasa, ‘no-party system’ of government since he won power in 1986, now wants to lift the ban on multi-party Kampala and Kigali back rival politics. He told delegates at an apprehensive congress of the ruling National Resistance Movement at militias and may be preparing for Kyankwanzi, north of Kampala, on 26 March, that they should accommodate those politicians who had another direct confrontation over persuaded ‘about 20 per cent’ of Ugandans to vote against his no-party system. The NRM would remain Congo’s mineral riches. unchanged, a broad church: ‘Those who want to experiment again with political parties can do so alongside the Movement, which should maintain its present identity’. So the no-party system (with its KENYA 3massive state subventions) is to compete with others in the presidential election due in 2006. The change of heart is more pragmatic than ideological. The NRM’s middle ranks are increasingly Victory is not enough calling for political liberalisation and modernisation. They also want more power within the Movement Two interlinked questions gnaw at over its ruling clique, who have been conspicuously enjoying the spoils of government. -

Kasese NRM Cadres Re-Group for 2021 Elections

20 NEW VISION, Monday, December 2, 2019 REGIONAL NEWS IN 2016, THE FORUM FOR DEMOCRATIC CHANGE WON ALL THE SIX PARLIAMENTARY AND LOCAL COUNCIL SEATS Kasese NRM cadres re-group for 2021 elections KASESE chairperson, Fred Businge, dubbed Thwabirighana (we met to lay strategies of winning have refused) against the By John Thawite back the seats. Government. They camped at Rwenzori After outlining numerous The National Resistance High School in Ibanda-Kyanya achievements under the NRM Movement (NRM) party town council to devise ways of compared to the previous cadres in Kasese district ‘liberating’ Kasese. regimes, Bamusedde, a have devised a strategy to The retreat was held under former journalist and current ‘dislodge the Opposition’ from the theme: Strengthening NRM chairperson of the District dominating the political space ideology amongst its cadres as Elders’ Forum, rhetorically in the Rwenzori region. a vehicle to sustainable wealth asked: “What do the people of This was during a three-day creation in Kasese district. this district want?” retreat last week. In the 2016 He said Kasese should be general elections, the Forum grateful for the improved for Democratic Change (FDC) BETWEEN THE LINES services. won all the six parliamentary n Masereka also and most of the district council challenged the cadres to Rwenzururu conflict Bamusedde addressing cadres at Rwenzori High School on Friday. Photo by John Thawite seats. use the retreat to examine The author of the Obusinga Dr Crispus Kiyonga, James their weaknesses and to Bwa Rwenzururu constitution Criminal Court (ICC) over ruling party better if they want municipality. It will have an Mbahimba, Boas Kafuda, Elijah forgive each other. -

Exclusionary Elite Bargains and Civil War Onset: the Case of Uganda

Working Paper no. 76 - Development as State-making - EXCLUSIONARY ELITE BARGAINS AND CIVIL WAR ONSET: THE CASE OF UGANDA Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre August 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © S. Lindemann, 2010 This document is an output from a research programme funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development. However, the views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Crisis States Research Centre Exclusionary elite bargains and civil war onset: The case of Uganda Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre Uganda offers almost unequalled opportunities for the study of civil war1 with no less than fifteen cases since independence in 1962 (see Figure 1) – a number that makes it one of the most conflict-intensive countries on the African continent. The current government of Yoweri Museveni has faced the highest number of armed insurgencies (seven), followed by the Obote II regime (five), the Amin military dictatorship (two) and the Obote I administration (one).2 Strikingly, only 17 out of the 47 post-colonial years have been entirely civil war free. 7 NRA 6 UFM FEDEMO UNFR I FUNA 5 NRA UFM UNRF I FUNA wars 4 UPDA LRA LRA civil HSM ADF ADF of UPA WNBF UNRF II 3 Number FUNA LRA LRA UNRF I UPA WNBF 2 UPDA HSM Battle Kikoosi Maluum/ UNLA LRA LRA 1 of Mengo FRONASA 0 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Figure 1: Civil war in Uganda, 1962-2008 Source: Own compilation. -

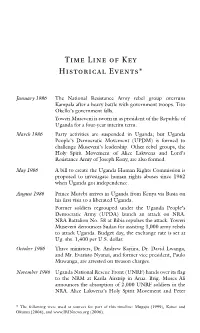

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

How Can We Survive Here?” WATCH the Impact of Mining on Human Rights in Karamoja, Uganda

HUMAN RIGHTS “How Can We Survive Here?” WATCH The Impact of Mining on Human Rights in Karamoja, Uganda “How Can We Survive Here?” The Impact of Mining on Human Rights in Karamoja, Uganda Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0961 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www. Human Rights Watch.org FEBRUARY 2014 978-1-62313-0961: “How Can We Survive Here?” The Impact of Mining on Human Rights in Karamoja, Uganda Summary and Recommendations ........................................................................................ 1 Methodology ................................................................................................................... -

State Surveillance in Uganda

For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda 1 Privacy International thanks the following individuals and organisations: BBC Newsnight Netzpolitik The Citizen Lab (University of Toronto, Canada) Claudio Guarnieri We also acknowledge the dozens of individuals and organisations in Uganda, the United Kingdom and Germany who cannot be named. A handful of these took significant risk to share information with us, for which we are grateful. This report is primarily based on original documentation provided in confidence to Privacy International. Privacy International is solely responsible for the content of this report. For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda October 2015 www.privacyinternational.org 3 For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence building, Mbuya Hill, 2012. Photo obtained by Privacy International. 4 For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda List of Acronyms A4C Activists for Change CCTV Closed-Circuit Television CDF Chief of Defence Forces CIID Police Criminal Investigations and Intelligence Directorate CMI Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence ESO External Security Organisation FDC Forum for Democratic Change ICT Information and Communication Technology IGP Inspector General of Police ISO Internal Security Organisation IT Information Technology JIC Joint Intelligence Committee LAN Local Area Network MP Member of Parliament NRA National Resistance Army NRM National Resistance Movement RICA Regulation of Interception of Communications Act (2010) UCC Uganda Communications Commission UPDF Uganda People's Defence Force UPF Uganda Police Force 5 For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda Executive Summary Yoweri Museveni was re-elected to his fifth term as President of Uganda in February 2011. -

The Blood Bath in Kasese District Western Uganda

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 11 (2018) pp.: 74-94 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper The Blood Bath In Kasese District Western Uganda. Nabukeera Madinah* Lecturer Kyambogo University Faculty of Arts and Social ScienceDepartment of History and Political Science ABSTRACT:This manuscript analyzed the aftermath of Kasese Account. A mixed method was used and both interviews and secondary Information was collected from local people and secondary sources i.e., face book pages, videos, tweets, newspapers, local television stations news and political discussions.A team of research assistants interviewed, various people in the affected areas includingthe people representatives, local leaders, Resident District Commissioners (RDCs), some survivors and grieving families in the Rwenzori region. This research aimed to answer eightresearch questions; Why was the Omusinga’s Palace at Buhikira attacked? Why King Mumbere was arrested? Who are the royal Guards? How many people were at the palace at the time of attacking the Palace? Did Mumbere defy president Museveni’s call before the attack? What is the mystery behind the creation of the Yiira Republic? and what are the effects of the Rwenzori saga? Results indicated that, Ministerial Commission set for Kajura (2005) should be reviewed and implemented in order to solve the long standing tribal conflicts and land tensions in the Rwenzori region. Key words;Rwenzururu Kingdoms, ethnic conflict, Kasese, Blood bath, Police and Army. Received 17 October, 2018; Accepted 03 Novenber, 2018 © The author(s) 2018. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. INTRODUCTION The monarch of the Rwenzururu Kingdom rules over the Bakonzo ethnic group and inhabitants of the Rwenzori Mountains.