State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Botswana

BIDPA Publications Series BIDPA Working Paper 45 Synthetic Gem QualityOctober 2016 Diamonds and their Potential Impact on the Botswana Economy Technology and the Nature of Active Citizenship: The Case of Botswana Roman Grynberg Margaret Sengwaketse MolefeMasedi B. Motswapong Phirinyane Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis BOTSWANA INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT POLICY ANALYSIS Synthetic Gem Quality Diamonds and their Potential Impact on the Botswana Economy BIDPA The Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA) is an independent trust, which started operations in 1995 as a non-governmental policy research institution. BIDPA’s mission is to inform policy and build capacity through research and consultancy services. BIDPA is part-funded by the Government of Botswana. BIDPA Working Paper Series The series comprises of papers which reflect work in progress, which may be of interest to researchers and policy makers, or of a public education character. Working papers may already be published elsewhere or may appear in other publications. Molefe B. Phirinyane is Research Fellow at the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis. ISBN: 978-99968-451-3-0 © Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis, 2016 Disclaimer The views expressed in this document are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of BIDPA. Technology and the Nature of Active Citizenship: The Case of Botswana TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ...................................................................................................................... -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

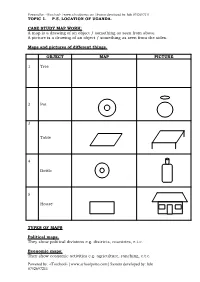

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of January 2017

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY 2017 Issue Date: 6th February 2017 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. National Overview Tension continues to rise in the Rwenzori sub region following the re-arrest of the King (Omusinga) Charles Wesley Mumbere of the Rwenzururu Kingdom (Obusinga Bwa Rwenzururu). He had been arrested in December 2016 on charges related to terrorism, aggravated robbery and attempted murder.1 These charges stemmed from attacks on police officers and police installations in the region in the last couple of months. King Mumbere was re-arrested just hours after Jinja High Court released him on bail. Prior to the re- arrest, one of the bail conditions was that he should not go to his Kingdom. The re-arrest of the King has not gone down well with some sections of his Kingdom. Area Members of the Parliament have condemned the re-arrest saying it was betrayal of the entire kingdom by the President of Uganda, and that the re-arrest was unlawful.2 However Police say King Mumbere was re-arrested because the latest investigations discovered other charges which he individually committed during the clashes in the region.3 The re-arrest of the King has the possibility of worsening the already precarious situation. In the last three years, more than three hundred (300) people have been killed, military installations attacked, houses, property and domestic livestock destroyed and many people injured in a conflict that is multidimensional. -

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of July 2014

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JULY 2014 Issue Date: August 5, 2014 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. INTRODUCTION The following is a Monthly Conflict Assessment Report provided by the USAID Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity and Peace (SAFE) Program for July 2014. The SAFE Program conducts monthly conflict assessments to better understand and respond to conflict patterns and trends as they develop throughout Uganda. Information is primarily filtered through SAFE’s trained Conflict Monitors who report on conflict incidents that occur in their communities. SAFE has Conflict Monitors based in West Nile, Acholi, Bunyoro and Karamoja sub regions, Gulu. The information provided by the Conflict Monitors is supplemented with reports issued by the media and civil society organizations (CSOs). The SAFE Program verifies reported incidents for accuracy. For a more detailed description of the monthly conflict assessment methodology, please refer to Appendix A. Seven Categories of conflicts are monitored in the Monthly Conflict Assessment: Land-related conflict Politically-motivated conflict Socio-ethnic conflict Ethnic conflict Conflict motivated by socio-economic issues or poverty Spill over and on-going conflicts that have expanded into new districts/countries Other conflicts that do not fall into the first six categories (see Annex B for the types of conflicts) The conflicts are additionally disaggregated by industry or sector, where relevant (for example, oil and gas, mining, infrastructure, manufacturing, and agriculture). -

Hdr- Botswana 2005

Botswana Human Development Report 2005 HARNESSING SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Published for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) i Copyright- 2005 By the United Nations Development Programme, Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (+267) 3952121, Fax: (+267) 3956093 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the United Nations Development Programme, Botswana Concept,editing and design by OP Advertising (Pty) Ltd, Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (+267) 319 0317 Fax: (+267) 390 0396 Printed by Printing and Publishing Company of Botswana Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (+267) 3912844 ISBN 99912-0-5020 ii Foreword We live in an era in which knowledge is decisive in separating winners subsistence. Similar needs can be found in food processing and other from losers. It does not matter whether we look at these polar outcomes forms of light manufacturing. – winning and losing – at the level of nations, firms, or individuals: Knowledge is a necessary requirement for winning in today’s closely I should not be understood to be making the case for a focus on integrated and competitive world. Knowledge expands the achievement technologies that would trap Botswana in low value production. Mine is possibilities of those who have it. Lack of it diminishes them. a case for inclusive technological investment, and for access to both new and old technologies for poor people. Our advocacy, our The disparities in development outcomes between prosperous and rich educational, institutional, policy and infrastructure responses to nations, and between rich and poor individuals, are underpinned Botswana’s technology needs should not engender the exclusion of foremost by differential access to knowledge and information. -

National Broadband Strategy

MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS NATIONAL BROADBAND STRATEGY June 2018 Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 7 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 9 2 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ............................................................................................... 11 2.1 International Connectivity ................................................................................................................................. 11 2.2 National Backbone ................................................................................................................................................ 11 2.3 Backhauling .............................................................................................................................................................. 11 2.4 Mobile Coverage .................................................................................................................................................... -

The Use of ICT in the Greater Gaborone Area

The use of ICT in the greater Gaborone area by Motshidisi Kenneth Setimela Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Information and Knowledge Management) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof J Kinghorn MARCH 2018 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION: By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University – All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Aandag aan die probleem van die ‘digital divide’ het verskuif van die eerste dimensie, naamlik ongelyke toegang tot Informasie en Kommunikasietegnologie (IKT), na die tweede dimensie, naamlik ongelyke vaardighede om IKT voordelig te kan gebruik. Hierdie tesis handel oor ‘digital divide’ in die groter Gaborone area, in besonder met betrekking tot die tweede dimensie. ‘n Belangrike komponent van die studie behels ‘n gevallestudie wat deur middel van ‘n vraeboog uitgevoer is in Gaborone. Hoofstuk 1 bespreek die navorsingsvraag en agtergrond Hoofstuk 2 bied ‘n uitgebreide literatuuroorsig oor die problematiek en relevant teoriee Hoofstuk 3 sit die gevallestudie uiteen Hoofstuk 4 bied die resultate van die gevallestudie Hoofstuk 5 maak gevolgtrekkings en voorstelle op grond van die navorsing iii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za SUMMARY The focus on the digital divide has shifted from the first order focus on on the gap between those who have access to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and those do not, to the second order question related to the skills to beneficially use ICT or not. -

Strategies Information and Communication Technology Managers Use to Build Employee Competencies Thulaganyo Arnold Rabogadi Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2017 Strategies Information and Communication Technology Managers Use to Build Employee Competencies Thulaganyo Arnold Rabogadi Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Databases and Information Systems Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Thulaganyo Rabogadi has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Cheryl McMahan, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Jaime Klein, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Ify Diala, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2017 Abstract Strategies Information and Communication Technology Managers Use to Build Employee Competencies by Thulaganyo Arnold Rabogadi MBA, De Montfort University, UK, 2006 BEng, Anglia Ruskin University, UK, 1995 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University April 2017 Abstract The World Economic Forum (WEF) found that Botswana’s information and communication technology (ICT) networked readiness index (NRI) had declined from position 89 in 2012 to 104 in 2015. -

Internet Finance to Smes in Botswana

Internet finance to SMEs in Botswana – A field study Department of Business Administration International Business Bachelor thesis Spring 2017 Authors: Paul Järvinen 1995/11/06 Ludvig Axfjord 1994/02/27 Tutor: Richard Nakamura Acknowledgements We would first and foremost like to thank the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency for making our journey possible. Furthermore, we would like to extend our gratitude to Kent and Mattias Nilsson for their continuous support and help, especially when things got a bit rough. We are also very grateful for the help we got from Quincy Moloi and Shadrack Shaduf Baaitse, who were indispensable to us and helped us make new contacts and experiences in Botswana. We would like to thank our tutor, Richard Nakamura, for helping us apply for MFS and supporting us throughout our research. And lastly, many thanks to Dave and Leonette Bethell who received us, and welcomed us to Africa in a phenomenal way; you were always there and supported us throughout our stay. 2 Abstract Title: Internet finance to SMEs in Botswana - A field study Authors: Axfjord, Ludvig and Järvinen, Paul Tutor: Nakamura, Richard Background and Problem: The Botswana government seeks to diversify its economy through encouraging entrepreneurship and aiding them in accessing finance. Furthermore, the Internet expansion in Botswana is on a rise and this creates an opportunity for online finance to expand. A larger extent of adoption of online financial services has been proven to aid SMEs in their development as well as being fruitful for the society as a whole; still the adoption of online financial services among Botswana SMEs is limited.