DRP WISER Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

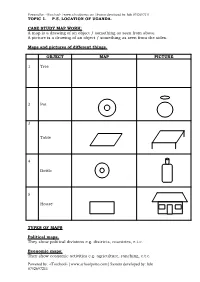

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2

CONTENTS State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Methodology 5 3.0 Country Context 6 3.1 Political Economy 6 3.2 Political Enviroment 6 3.3 ICT Status 7 3.4 State Co-ownership of Network Operators and Infrastructure 8 3.5 Legal Protection of Human Rights 9 3.6 Status of ICT Legislation 11 4.0 Overview of Information Controls in Place 13 4.1 Content Controls in Legislation 13 4.1.1 Offensive Communication 14 4.1.2 Pornographic or Obscene Content 15 4.1.3 Hate Speech 16 4.1.4 Defamation 17 4.1.5 False Information “Fake news” 18 4.1.6 National Security and Terrorism 19 4.1.7 Censorship 20 4.1.8 Internet Shutdowns 21 4.1.8 Other Restrictions 22 5.0 Internet Intermediaries and Internet Freedom 23 5.1 Limitation of Liability on Intermediaries 23 5.2 Imposition of Liability on Intermediaries 24 5.3 Restrictions Imposed by Intermediaries 26 5.4 Violation of Privacy Rights 28 5.4.1 Processing and Disclosure of Personal Information 28 5.4.2 Retention of Content Data 29 5.4.3 Surveillance and Interception of Communication 30 5.4.4 Poor Accountability of Intermediaries 32 5.5 Inadequate Complaint Handling Frameworks and Remedies 33 5.6 Pushbacks Against Violations and the Promotion of Rights 34 6.0 Conclusion and Recommendations 36 6.1 Conclusion 36 6.2 Recommendations 37 6.2.1 Government 37 6.2.2 Intermediaries 38 6.3.3 Media 38 6.3.4 Academia 38 6.3.5 Technical Community 39 6.3.6 Civil Society 39 6.3.7 Public 39 3 State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 1.0 Introduction Growing use of the internet and related technologies has provided new spaces for advancing the right to freedom of expression (FOE), promoted access to information, and spurred innovation and socio-economic growth in various African countries. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of January 2017

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY 2017 Issue Date: 6th February 2017 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. National Overview Tension continues to rise in the Rwenzori sub region following the re-arrest of the King (Omusinga) Charles Wesley Mumbere of the Rwenzururu Kingdom (Obusinga Bwa Rwenzururu). He had been arrested in December 2016 on charges related to terrorism, aggravated robbery and attempted murder.1 These charges stemmed from attacks on police officers and police installations in the region in the last couple of months. King Mumbere was re-arrested just hours after Jinja High Court released him on bail. Prior to the re- arrest, one of the bail conditions was that he should not go to his Kingdom. The re-arrest of the King has not gone down well with some sections of his Kingdom. Area Members of the Parliament have condemned the re-arrest saying it was betrayal of the entire kingdom by the President of Uganda, and that the re-arrest was unlawful.2 However Police say King Mumbere was re-arrested because the latest investigations discovered other charges which he individually committed during the clashes in the region.3 The re-arrest of the King has the possibility of worsening the already precarious situation. In the last three years, more than three hundred (300) people have been killed, military installations attacked, houses, property and domestic livestock destroyed and many people injured in a conflict that is multidimensional. -

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of July 2014

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JULY 2014 Issue Date: August 5, 2014 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. INTRODUCTION The following is a Monthly Conflict Assessment Report provided by the USAID Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity and Peace (SAFE) Program for July 2014. The SAFE Program conducts monthly conflict assessments to better understand and respond to conflict patterns and trends as they develop throughout Uganda. Information is primarily filtered through SAFE’s trained Conflict Monitors who report on conflict incidents that occur in their communities. SAFE has Conflict Monitors based in West Nile, Acholi, Bunyoro and Karamoja sub regions, Gulu. The information provided by the Conflict Monitors is supplemented with reports issued by the media and civil society organizations (CSOs). The SAFE Program verifies reported incidents for accuracy. For a more detailed description of the monthly conflict assessment methodology, please refer to Appendix A. Seven Categories of conflicts are monitored in the Monthly Conflict Assessment: Land-related conflict Politically-motivated conflict Socio-ethnic conflict Ethnic conflict Conflict motivated by socio-economic issues or poverty Spill over and on-going conflicts that have expanded into new districts/countries Other conflicts that do not fall into the first six categories (see Annex B for the types of conflicts) The conflicts are additionally disaggregated by industry or sector, where relevant (for example, oil and gas, mining, infrastructure, manufacturing, and agriculture). -

Report on Preliminary Examination Activities (2020)

Le Bureau du Procureur The Office of the Prosecutor Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2020 14 December 2020 Report on Preliminary Examination Activities 2020 14 December 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. SITUATIONS UNDER PHASE 1 ............................................................................. 9 II. SITUATIONS UNDER PHASE 2 (SUBJECT-MATTER JURISDICTION) ... 21 BOLIVIA ............................................................................................................. 21 VENEZUELA II .................................................................................................... 24 III. SITUATIONS UNDER PHASE 3 (ADMISSIBILITY) ....................................... 27 COLOMBIA ......................................................................................................... 27 GUINEA .............................................................................................................. 40 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ......................................................................... 45 VENEZUELA I ..................................................................................................... 50 IV. COMPLETED PRELIMINARY EXAMINATIONS ............................................ 55 PALESTINE.......................................................................................................... 55 IRAQ/UK ............................................................................................................ 59 NIGERIA ............................................................................................................ -

Identity Manipulation and Spontaneous Mobilization: the Persistence of Low-Intensity Conflict in the Rwenzori Region

IDENTITY MANIPULATION AND ISSN: 2531-9744 SPONTANEOUS MOBILIZATION: THE PERSISTENCE OF LOW-INTENSITY CONFLICT IN THE RWENZORI REGION indicated on the map below). Violence was mainly directed against personnel and governmental Stefano Ruzza structures, but civilians and the king palace of another cultural institution, the "Bwamba Among the violent events that have aected – and Kingdom" (Obudhinghiya bwa Bwamba), were unfortunately still aect – Uganda, a prominent also attacked. The level of coordination behind the place is undoubtedly occupied by the insurgency in attacks, which aected a very wide area within a the northern regions, the key gure of which is the short period of time, led analysts to believe that infamous Joseph Kony. Less well known, also due to some unruly Islamists based in Congo (particularly lower levels of violence, are the vicissitudes coming from or linked to the Alliance of aecting the western portion of the country, in Democratic Forces – ADF) organized them, even if particular the region called Rwenzori: an area on the this remains a groundless hypothesis. The attacks border with Congo, which has a long tradition of of July 2014 and the reprisals that followed caused rebellion against the Ugandan government. It has the deaths of about a hundred people, but the also become infamous for a series of episodes that existence of several mass graves with unidentied have caused several hundred deaths altogether. bodies has led to an estimation that doubles the number of initial estimates. In the second The rst episode, and also the bloodiest, dates back half of 2014, the government rushed to start to July 2014, when some hundreds of young people a rehabilitation program that ended with an aliated to one of the cultural institutions of the amnesty being granted to about 500 of those who area, the "Rwenzururu Kingdom" (Obusinga bwa participated in the attacks. -

A History of the Heritage Economy in Yoweri Museveni's Uganda

Journal of Eastern African Studies ISSN: 1753-1055 (Print) 1753-1063 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 A history of the heritage economy in Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda Derek R. Peterson To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson (2016) A history of the heritage economy in Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10:4, 789-806, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1272297 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2016.1272297 Published online: 01 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjea20 Download by: [University of Cambridge] Date: 01 February 2017, At: 07:29 JOURNAL OF EASTERN AFRICAN STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 10, NO. 4, 789–806 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2016.1272297 A history of the heritage economy in Yoweri Museveni’s Uganda Derek R. Peterson Department of History, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY When the National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power in Received 19 August 2016 1986, its cadres overflowed with reformist zeal. They set out to Accepted 9 December 2016 transform Uganda’s public life, put an end to ethnic division, and KEYWORDS promote local democracy. Today much of this reformist energy Yoweri Museveni; elections; has dissipated, and undemocratic kingdoms largely define the heritage; traditional cultural landscape. This essay attempts to explain how these medicine; Rwenzururu things came to pass. It argues that the heritage economy offered NRM officials and other brokers an ensemble of bureaucratic techniques with which to naturalize and standardize cultures. -

Portrait of a Failed Rebellion: an Account of Rational, Sub-Optimal Violence in Western Uganda

Forthcoming: Rationality and Society Portrait of a Failed Rebellion: An Account of Rational, Sub-optimal Violence in Western Uganda * By LUCY HOVIL AND ERIC WERKER Abstract While newspaper reports typically describe anti-civilian violence in civil war as resulting from hatred or anarchy, there is an emerging literature that interprets these processes as calculated, strategic actions of war makers. We argue that this literature overestimates the strategic value of violence by focusing on conflicts where this strategy is used deliberately and on a massive scale. Our analysis examines the violence in a failed, peripheral rebellion in western Uganda and finds that the brutality was premeditated; however the gains to the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) rebels were not military. Instead, we argue that anti-civilian violence in western Uganda stems from the financier-insurgent relationship that promoted a high level of violence in response to divergent interests, unequal access to information, and contracting limitations. In other words, civilians were victimized in order that the ADF could keep their outside funding. Key words: civilian violence; civil war; insurgency; war financing; Uganda. * Authors’ names listed alphabetically. Refugee Law Project, Makerere University, P.O. Box 6016, Kampala, Uganda; Department of Economics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]. This draft: February 23, 2004. We wish to thank Robert Bates, Zachary Lomo, Charles Cohen, Robert Trager, Jeremy Weinstein, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. Winifred Agabo, Emmanuel Bagenda, and Elias Lubega provided excellent research assistance in Uganda. We are grateful to the Ugandan National Council on Science and Technology for permission to conduct the field research. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 241/Monday, December 16, 2019/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 241 / Monday, December 16, 2019 / Notices 68545 Burden Estimates: Evaluation, tel.: 202–622–2490; Designated pursuant to section 1(a)(ii)(A) Number of Respondents: 110. Assistant Director for Licensing, tel.: of E.O. 13818 for being a foreign person who Estimated Annual Burden for 202–622–2480; or Assistant Director for is responsible for or complicit in, or has Standards and Template: 8 hours. Regulatory Affairs, tel.: 202–622–4855. directly or indirectly engaged in, serious human rights abuse. Total Annual Burden: 880 hours. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Frequency of Response: Annual. 6. KOCNER, Marian, Slovakia; DOB 17 Electronic Availability May 1963; POB Ruzomberok, Slovakia; Comments: On September 4, 2019, the nationality Slovakia; Gender Male; Passport OCC issued a notice for 60 days of The Specially Designated Nationals 4305176196 (Slovakia) expires 31 Mar 2025 comment concerning this collection, 84 and Blocked Persons List and additional (individual) [GLOMAG]. FR 46604. No comments were received. information concerning OFAC sanctions Designated pursuant to section 1(a)(ii)(A) Comments continue to be invited on: programs are available on OFAC’s of E.O. 13818 for being a foreign person who (a) Whether the collection of website (https://www.treasury.gov/ofac). is responsible for or complicit in, or has information is necessary for the proper directly or indirectly engaged in, serious performance of the functions of the Notice of OFAC Action(s) human rights abuse. OCC, including whether the information 7. AL–WARFALLI, Mahmud (a.k.a. AL– On December 10, 2019, OFAC WERFALLI, Mahmoud; a.k.a. AL– has practical utility; determined that the property and WERFALLI, Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf), (b) The accuracy of the OCC’s interests in property subject to U.S.