The Colonial Roots of Internal Conflict in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escalating Land Conflicts in Uganda

ESCALATING LAND CONFLICTS IN UGANDA A review of evidence from recent studies and surveys By Margaret A. Rugadya 1 June, 2009 For the International Republican Institute (IRI) (Funder) And the Uganda Round Table Foundation (Implementer) Abstract : Despite progress made to address land-related legislative issues, the land sector in Uganda faces several challenges that include insecurity of tenure, overlapping and conflicting land rights, and glaring inequity in access to and ownership of land. Conflicts that are a consequence of colonial legacy are exacerbated in the majority of cases by competition over access, use and transfer of scarce land and natural resources, ever increasing population densities, largely driven by the high population growth rate, unsustainable agricultural practices, and policy and institutional weaknesses. Possibility of increasing conflict is largely driven by competition for influence and power which comes with demonstrated control over land matters such as ownership, allocation and access especially as regards overlapping land rights. Structurally, Uganda’s population is growing at a high rate of 3.2 per cent and is projected to shoot up to 39.3 million in the year 2015 and 54.9 million in 2025 due to high fertility rate, set next to deficits in land governance, corruption and ignorance of the law, the automatic escalation of land conflict to phenomenal levels, is not only well deserved but is clearly foretold. 1 Research Fellow at Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, University of Maastricht and Director, Associates Foundation; a public policy research foundation, Email: [email protected] , Tel. 041-4541988 i CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS ................................................................................................. -

Annual Report of the Colonies. Uganda 1920

This document was created by the Digital Content Creation Unit University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2010 COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL. No. 1112. UGANDA. REPORT FOR 1920 (APRIL TO DECEMBER). (For Report for 1919-1920 see No. 1079.) LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any T3ookscller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: IMPERIAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONC-ON, W.C.2, and 28, ABINGDON STREET, LONDON, S.W.I; 37, PETER STREET, MANCHESTER; 1, ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF; 23, FORTH STREET, EDINBURGH; or from EASON & SON. LTD., 40-41, LOWER SACKVII.I-E STREET, DUBLIN. 1922. Price 9d. Net. INDEX. PREFACE I. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS II. GOVERNMENT FINANCE III. TRADE, AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRIES IV. LEGISLATION V. EDUCATION VI. CLIMATE AND METEOROLOGY VII. COMMUNICATIONS.. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS' RECEIVED &0dUM£NT$ DIVISION -fTf-ViM-(Hff,>itmrtn«l,.ni ii ii in. No. 1112. Annual Report ON THE Uganda Protectorate FOR THE PERIOD 1st April to 31st December 1920.* PREFACE. 1. Geographical Description.—The territories comprising the Uganda Protectorate lie between Belgian Congo, the Anglo- Egyptian Sudan, Kenya, and the country known until recently as German East Africa (now Tanganyika Territory). The Protectorate extends from one degree of south latitude to the northern limits of the navigable waters of the Victoria Nile at Nimule. It is flanked on the east by the natural boundaries of Lake Rudolf, the river Turkwel, Mount Elgon (14,200 ft.), and the Sio river, running into the north-eastern waters of Lake Victoria, whilst the outstanding features on the western side are the Nile Watershed, Lake Albert, the river Semliki, the Ruwenzori Range (16,794 ft.), and Lake Edward. -

Museveni Urges Elected Kyabazinga on Unity

10 NEW VISION, Monday, September 1, 2014 REGIONAL NEWS Museveni urges elected Kyabazinga on unity KAMPALA meeting a delegation of 16 Museveni said. He commended kingdom officials from Busoga the paramount chiefs upon the By Vision Reporter led by Nadiope at State House achievement and urged them Entebbe. He congratulated to unite the people of Busoga President Yoweri Museveni them upon the successful for the sake of development has urged the new Kyabazinga election of their king, saying instead of splitting them. of Busoga, William Gabula in the past, elections of a Nadiope thanked the Nadiope IV, to unite his Kyabazinga were marred by President for securing peace in people and rally them for lack of quorum. Busoga and pledged to unify development. He added that “I congratulate you upon and reconcile his people for so much time has been lost your victory. You had the the good of Busoga. Nadiope’s and yet there is much that quorum of 10 people out of 11 coronation and enthronement needs to be done. who voted for you as required has been scheduled for President Museveni meeting Nadiope (centre) at State House Entebbe. Photo by PPU The President was recently by the Busoga constitution,’’ September 13, at Bugembe. Chief prince installs rival Wambuzi as Kyabazinga JINJA death of Henry Wako Muloki a spear, shield and a drum to in September 2008, declared Wambuzi at his private palace By Charles Kakamwa that Wambuzi, Muloki’s heir, in Nakabango village, Jinja was the right person to ascend district. He explained that what The disagreement over the the throne. -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Songs of Soldiers

SONGS OF SOLDIERS DECOLONIZING POLITICAL MEMORY THROUGH POETRY AND SONG by Juliane Okot Bitek BFA, University of British Columbia, 1995 MA, University of British Columbia, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2019 © Juliane Okot Bitek, 2019 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Songs of Soldiers: Decolonizing Political Memory Through Poetry And Song submitted by Juliane Okot Bitek in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies Examining Committee: Prof. Pilar Riaño-Alcalá, (Social Justice) Co-supervisor Prof. Erin Baines, (Public Policy, Global Affairs) Co-supervisor Prof. Ashok Mathur, (graduate Studies) OCAD University, Toronto Supervisory Committee Member Prof. Denise Ferreira da Silva (Social Justice) University Examiner Prof. Phanuel Antwi (English) University Examiner iii Abstract In January 1979, a ship ferrying armed Ugandan exiles and members of the Tanzanian army sank on Lake Victoria. Up to three hundred people are believed to have died on that ship, at least one hundred and eleven of them Ugandan. There is no commemoration or social memory of the account. This event is uncanny, incomplete and yet is an insistent memory of the 1978-79 Liberation war, during which the ship sank. From interviews with Ugandan war veterans, and in the tradition of the Luo-speaking Acholi people of Uganda, I present wer, song or poetry, an already existing form of resistance and reclamation, as a decolonizing project. -

Bigwala Mus Ic and Dance of the Bas Oga People

BIGWALA MUSIC AND DANCE OF THE BASOGA PEOPLE written by James Isabirye 2012 Background The Basoga are Bantu speaking people who live in southeastern Uganda. They are neighbors to the Baganda, Bagwere, Basamia, Banyoli and Banyoro people. The Basoga are primarily subsistence agricultural people. "Bigwala” is a Lusoga language term that refers to a set of five or more monotone gourd trumpets of different sizes. The music of the trumpets and the dance performed to that music are both called “Bigwala”. Five drums accompany “Bigwala” music and they include a big drum “Engoma e ne ne ”, a long drum “Omugaabe,” short drum “Endyanga”, a medium size drum “Mbidimbidi” and a small drum “Enduumi ” each of which plays a specific role in the set. Bigwala heritage is of significant palace / royal importance because of its ritualistic role during burial of kings, coronations and their anniversaries and stands as one of the main symbols of Busoga kingship. When King Henry Wako M uloki passed away on 1st September 2008, the "Bigwala" players were invited to Nakabango palace and Kaliro burial ground to perform their funeral function. 1 During the coronation of late king Henry Wako Muloki on 11th February 1995; the Bigwala players performed their ritual roles. It is important to note that Busoga kingdom like all others had been abolished in 1966 by the Ugandan republic government of Obote I and all aspects its existence were jeopardised including the Bigwala. The Kingship is the only main uniting identity which represents the Basoga, offers them opportunity to exist in a value system, focuses their initiatives to deal with development issues with in the framework of their ethnic society and connects them to their cherished past. -

———— “Mudo”: the Soga 'Little Red Riding Hood'

LILLIAN BUKAAYI TIBASIIMA ———— º “Mudo”: The Soga ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ABSTRACT This essay analyses the social underpinnings of the oral tale of “Mudo,” which belongs to the Aarne–Thompson tale type 333, along with a group of similar tales that resemble the action and movement of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Basic to the exposition is Adolf Bastian’s assertion of the fundamental similarity of ideas between all social groups. In the “Mudo” story and its Ugandan variants, the victim is a solitary little girl and the villain a male ogre who devises ways of eating her; the ogre is mostly successful, although in some variants the girl manages to escape. Although these tales come from a great range of cultures and different geographical locations, and the counterpart of the ogre in the European tales is a wolf in disguise, they share elements of plot, characteriza- tion, and motif, and address similar concerns. Introduction USOGA IS PART OF EAS TERN UGANDA, surrounded by water. The B Rev. Fredrick Kisuule Kaliisa1 notes: To the west is river Kiira (Nile) marking the boundary between Buganda and Busoga. To the East is river Mpologoma separating Busoga from Bukedi. To the North are river Mpologoma and Lake Kyoga, forming the boundary be- tween Busoga and Lango. To the south, is Lake Victoria (Nalubaale). It might be the result of the geographical location of Busoga that ogre stories were composed to warn the people against impending harm if they went out alone and stayed in secluded places. Nnalongo Lukude emphasizes this: Historically, Busoga was surrounded by bodies of water and forests, it was very bushy and as a result harboured many wild animals, some of which were man-eaters. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

Challenges of Development and Natural Resource Governance In

Ian Karusigarira Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival The road that the community expects to take in each generation is inspired and shaped by its memories of former heroic ages —Smith, D.A. (2009) Ian Karusigarira PhD Candidate, Graduate School of Global Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan Abstract In revolutionary political systems—such as Uganda’s—lies a strong collective memory that organizes and enforces national identity as a cultural property. National identity nurtured by the nexus between lived representations and narratives on collective memory of war, therefore, presents itself as a kind of politics with repetitive series of nation-state narratives, metaphorically suggesting how the putative qualities of the nation’s past reinforce the qualities of the present. This has two implications; it on one hand allows for changes in a narrative's cognitive claims which form core of its constitutive assumptions about the nation’s past. This past is collectively viewed as a fight against profanity and restoration of political sanctity; On the other hand, it subjects memory to new scientific heuristics involving its interpretations, transformation and distribution. I seek to interrogate the intricate memory entanglement in gaining and consolidating political power in Uganda. Of great importance are politics of remembering, forgetting and utter repudiation of memory of war while asserting control and restraint over who governs. The purpose of this paper is to understand and internalize the dynamics of how knowledge of the past relates with the present. This gives a precise definition of power in revolutionary-dominated regimes. Keywords: Memory of War, national narratives, victimhood, regime survival, Uganda ―75― 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示4.0国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival 1. -

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

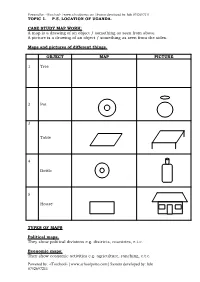

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

The History of Syphilis in Uganda

Bull. Org. mond. Santeh 1956, 15, 1041-1055 Bull. Wld Hith Org. THE HISTORY OF SYPHILIS IN UGANDA J. N. P. DAVIES, M.D., Ch.B., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. Professor of Pathology, Makerere College Medical School, Kampala, Uganda SYNOPSIS The circumstances of an alleged first outbreak of syphilis in Uganda in 1897 are examined and attention is drawn to certain features which render possible alternative explanations of the history of syphilis in that country. It is suggested that an endemic form of syphilis was an old disease of southern Uganda and that protective infantile inoculation was practised. The country came under the observation of European clinicians at a time when endemic syphilis was being replaced by true venereal syphilis. This process has now been completed, endemic syphilis has disappeared, and venereal syphilis is now widespread and a more serious problem than ever. This theory explains the observations of other writers and reconciles the apparent discrepancies between various reports. Until comparatively recent times the country now known as Uganda was cut off from the rest of the world. The Nile swamps to the north, the impenetrable Congo forest to the west, the mountains and the upland plateaux with the warrior Masai to the east, and the other immense difficul- ties of African travel, had protected the country from intrusion. In the southern lacustrine areas there had developed the remarkable indigenous kingdoms of Bunyoro and Buganda. These became conscious of the larger outside world about 1850, when a Baluch soldier from Zanzibar reached the court of the King of Buganda, the Kabaka Suna. -

Are Family Planning Programs Reaching the Disadvantaged? an Equity Case Study of Uganda

POLICY Brief September 2020 Are Family Planning Programs Reaching Authors: Kaja Jurczynska, the Disadvantaged? Kevin Ward, Lyubov Teplitskaya, Shiza Farid, and Kristin Bietsch An Equity Case Study of Uganda Introduction In just over a decade, the share of married women using modern methods of contraception in Uganda nearly doubled, increasing Equity in health means that from 18 percent in 2006 to 35 percent in 2016, and to a further 37 everyone has a fair opportunity 1 percent in 2019 (UBOS and ICF, 2018; FP2020, 2020). Uganda to reach their health potential, has cemented its commitment to family planning through the regardless of wealth, education, country’s first Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan for sex, age, race or ethnic group, 2015–2020 and subsequent pledges under the Family Planning residence, disability, and other 2020 (FP2020) partnership. Among its goals, Uganda has status or social group. committed to reducing inequities, particularly for those living in rural areas, adolescents, and those facing financial hardship (Ministry of Health, 2014; FP2020, 2017). Despite this progress, Uganda has experienced challenges in Box 1. HP’s Approach for meeting its family planning commitments for 2020 and 2021, Diagnosing Inequity in including those that are equity focused. For example, unmet Family Planning Programs need is higher than desired, at one quarter of all married women compared to the goal of 10 percent by 2020. The use of modern The approach answers the “who, contraceptive methods lags behind the 2020 goal of 50 percent what, and where” of inequities in (FP2020, 2019). While inadequate funding of family planning family planning: activities remains a key barrier to progress (Wanyana et al., 2019), better directing information and services for those women who • Who is experiencing inequity? need them most could address longstanding inequities while also • What components of bolstering uptake and improving allocative efficiency.