Challenges of Development and Natural Resource Governance In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

A Call to Action to Enhance Filovirus Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response

Viruses 2014, 6, 3699-3718; doi:10.3390/v6103699 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Letter A Call to Action to Enhance Filovirus Disease Outbreak Preparedness and Response Paul Roddy Independent Epidemiology Consultant, Barcelona, 08010, Spain; E-Mail: [email protected] External Editor: Jens H. Kuhn Received: 8 September 2014; in revised form: 23 September 2014 / Accepted: 23 September 2014 / Published: 30 September 2014 Abstract: The frequency and magnitude of recognized and declared filovirus-disease outbreaks have increased in recent years, while pathogenic filoviruses are potentially ubiquitous throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, the efficiency and effectiveness of filovirus-disease outbreak preparedness and response efforts are currently limited by inherent challenges and persistent shortcomings. This paper delineates some of these challenges and shortcomings and provides a proposal for enhancing future filovirus-disease outbreak preparedness and response. The proposal serves as a call for prompt action by the organizations that comprise filovirus-disease outbreak response teams, namely, Ministries of Health of outbreak-prone countries, the World Health Organization, Médecins Sans Frontières, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Atlanta, and others. Keywords: Ebola; ebolavirus; Marburg virus; marburgvirus; Filoviridae; filovirus; outbreak; preparedness; response; data collection; treatment; guidelines; surveillance 1. Introduction Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Marburg virus disease (MVD) in human and non-human primates (NHPs) are caused by seven distinct viruses that produce filamentous, enveloped particles with negative-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid genomes. These viruses belong to the Filoviridae family and its Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus genera, respectively [1]. An eighth filovirus, Lloviu virus (LLOV), assigned to the third filovirus genus, Cuevavirus has thus far not been associated with human disease [2,3]. -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

Uganda 2015 Human Rights Report

UGANDA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uganda is a constitutional republic led since 1986 by President Yoweri Museveni of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party. Voters re-elected Museveni to a fourth five-year term and returned an NRM majority to the unicameral Parliament in 2011. While the election marked an improvement over previous elections, it was marred by irregularities. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The three most serious human rights problems in the country included: lack of respect for the integrity of the person (unlawful killings, torture, and other abuse of suspects and detainees); restrictions on civil liberties (freedoms of assembly, expression, the media, and association); and violence and discrimination against marginalized groups, such as women (sexual and gender-based violence), children (sexual abuse and ritual killing), persons with disabilities, and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) community. Other human rights problems included harsh prison conditions, arbitrary and politically motivated arrest and detention, lengthy pretrial detention, restrictions on the right to a fair trial, official corruption, societal or mob violence, trafficking in persons, and child labor. Although the government occasionally took steps to punish officials who committed abuses, whether in the security services or elsewhere, impunity was a problem. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were several reports the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. On September 8, media reported security forces in Apaa Parish in the north shot and killed five persons during a land dispute over the government’s border demarcation. -

Nakaseke Constituency: 109 Nakaseke South County

Printed on: Monday, January 18, 2021 16:36:23 PM PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, (Presidential Elections Act, 2005, Section 48) RESULTS TALLY SHEET DISTRICT: 069 NAKASEKE CONSTITUENCY: 109 NAKASEKE SOUTH COUNTY Parish Station Reg. AMURIAT KABULETA KALEMBE KATUMBA KYAGULA MAO MAYAMBA MUGISHA MWESIGYE TUMUKUN YOWERI Valid Invalid Total Voters OBOI KIIZA NANCY JOHN NYI NORBERT LA WILLY MUNTU FRED DE HENRY MUSEVENI Votes Votes Votes PATRICK JOSEPH LINDA SSENTAMU GREGG KAKURUG TIBUHABU ROBERT U RWA KAGUTA Sub-county: 001 KAASANGOMBE 014 BUKUUKU 01 TIMUNA/KAFENE 716 1 0 1 0 278 2 0 1 0 1 140 424 43 467 0.24% 0.00% 0.24% 0.00% 65.57% 0.47% 0.00% 0.24% 0.00% 0.24% 33.02% 9.21% 65.22% 02 LUKYAMU PR. SCHOOL 778 2 2 0 1 348 2 2 0 1 0 110 468 24 492 0.43% 0.43% 0.00% 0.21% 74.36% 0.43% 0.43% 0.00% 0.21% 0.00% 23.50% 4.88% 63.24% 03 BUKUUKU PRI. SCHOOL 529 0 0 1 1 188 0 1 0 0 0 74 265 3 268 0.00% 0.00% 0.38% 0.38% 70.94% 0.00% 0.38% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 27.92% 1.12% 50.66% Parish Total 2023 3 2 2 2 814 4 3 1 1 1 324 1157 70 1227 0.26% 0.17% 0.17% 0.17% 70.35% 0.35% 0.26% 0.09% 0.09% 0.09% 28.00% 5.70% 60.65% 015 BULYAKE 01 NJAGALABWAMI COMM. -

^Uganda Gazette “

Newspaper^Uganda JL JL W'W GazetteJ Authority“ Vol. XCV No. 71 6th December, 2002 Price: Shs. 1000 CONTENTS Page General Notice No. 467 of 2002. Ministry of Health—Notice .................... 575 THE MARRIAGE ACT, 1964. The Marriage Act—Notice ........................ 575 (Cap. 211). The Traffic and Road Safety Act—Notice ... 575 NOTICE. The Water Statute—Notice .................... 575 Under section 6 of the Act. The Electoral Commission—Notices .......... 576 PLACE FOR CELEBRATION OF MARRIAGES. The Trade Marks Act— Registration of applications 576-578 In exercise of the powers conferred upon me by section 6 Advertisements .............................................. 578 of the Marriage Act, I hereby licence the place of public worship mentioned in the Schedule hereto to be place for General Notice No. 466 of 2002. celebration of marriages. DECLARATION OF ALLIED HEALTH SCHEDULE ' PROFESSIONALS FOR PRIVATE PRACTICE. 1. Church — Christian Missionary Fellowship Whereas under section 30(a) - (e) of THE ALLIED Denomination— Born Again HEALTH PROFESSIONALS STATUTE 1996, the Place — Mengo following categories of Allied Health Professionals may Subcounty — Rubaga establish, engage in and manage private common health County — Kyadondo conditions, units: District — Kampala Dispensers Medical Clinical Officers HAJATI JANAT B. MUKWAYA, Medical Laboratory Technologists Minister of Justice & Constitutional Affairs. Physiotherapists Public Health Dental Officers And whereas other Allied Health Professionals may be General Notice No. 468 of 2002. declared by the Minister on the advice of the Allied Health Professionals' Council and the Uganda Medical and Dental THE TRAFFIC AND ROAD SAFETY Practitioners' Council, under subsection 30(f) of the Statute; (WEIGHBRIDGES) REGULATIONS, 1998. ESTABLISHMENT OF MBARARA WEIGHBRIDGE And whereas to enable other professionals to be declared under STATION. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Songs of Soldiers

SONGS OF SOLDIERS DECOLONIZING POLITICAL MEMORY THROUGH POETRY AND SONG by Juliane Okot Bitek BFA, University of British Columbia, 1995 MA, University of British Columbia, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2019 © Juliane Okot Bitek, 2019 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Songs of Soldiers: Decolonizing Political Memory Through Poetry And Song submitted by Juliane Okot Bitek in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies Examining Committee: Prof. Pilar Riaño-Alcalá, (Social Justice) Co-supervisor Prof. Erin Baines, (Public Policy, Global Affairs) Co-supervisor Prof. Ashok Mathur, (graduate Studies) OCAD University, Toronto Supervisory Committee Member Prof. Denise Ferreira da Silva (Social Justice) University Examiner Prof. Phanuel Antwi (English) University Examiner iii Abstract In January 1979, a ship ferrying armed Ugandan exiles and members of the Tanzanian army sank on Lake Victoria. Up to three hundred people are believed to have died on that ship, at least one hundred and eleven of them Ugandan. There is no commemoration or social memory of the account. This event is uncanny, incomplete and yet is an insistent memory of the 1978-79 Liberation war, during which the ship sank. From interviews with Ugandan war veterans, and in the tradition of the Luo-speaking Acholi people of Uganda, I present wer, song or poetry, an already existing form of resistance and reclamation, as a decolonizing project. -

Local Government Quarter 2 Expenditure Limits by Vote and Item

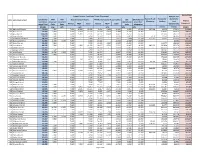

Unconditional Grant Non- Support Services Conditional Grant (Non-wage) Pension and wage Conditional IFMS IPPS Boards and Commisions PAF Monitoring and Accountability DSC EX Gratia and Hard to Reach Pension for Gratuity for Vote Local Government District Grant (Non- Recurrent Recurrent Operational Councillors' Allowances Teachers Local Component wage) Total Costs Costs Normal PRDP Total Normal PRDP Total costs allowances Governments 321469 o/w o/w o/w o/w o/w o/w 212103 212105 321401 501 Adjumani District 70,333 7,500 - 7,030 16,965 23,995 9,614 9,455 19,069 6,569 13,200 357,364 42,075 172,271 112,092 502 Apac District 70,438 7,500 - 7,030 5,902 12,932 17,234 6,313 23,547 11,758 14,700 - 328,001 763,115 164,460 503 Arua District 110,298 7,500 - 7,030 15,105 22,135 26,551 10,070 36,621 25,592 18,450 - 452,432 345,212 356,989 504 Bugiri District 50,557 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 12,143 - 12,143 9,933 13,950 4,171 71,372 385,066 155,982 505 Bundibugyo District 48,218 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 9,657 - 9,657 7,830 16,200 411,325 46,975 270,173 88,150 506 Bushenyi District 61,908 11,786 6,250 7,030 - 7,030 10,543 - 10,543 12,349 13,950 - - 88,534 222,435 507 Busia District 59,123 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 10,280 4,808 15,088 10,305 19,200 - 110,077 155,353 128,289 508 Gulu District 88,745 7,500 - 7,030 9,501 16,532 18,027 9,501 27,529 16,485 20,700 882,273 342,820 255,276 168,801 509 Hoima District 52,515 - - 7,030 - 7,030 14,124 - 14,124 12,162 19,200 - 627,237 136,974 214,390 510 Iganga District 71,706 7,500 - 7,030 - 7,030 19,245 - 19,245 19,480 18,450 -

Pdacl827.Pdf

Promoting Community-Based Distribution / Community Reproductive Health Worker Provision of DMPA Educational Visit to Uganda – Summary Report February 18 – 20, 2008 Family Health International • Plot 6 Kafu Road • Kampala, Uganda • 256 414 235035 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary II. Overview III. Introductory Session with Key Stakeholders in the Uganda CBD of DMPA Project IV. Meeting with Key Stakeholders and District Officials V. Field Trip to Luwero and Nakaseke Districts VI. Debriefing with Key Stakeholders and District Officials VII. The Way Forward – Country Team Planning Sessions VIII. Tour Reflections and Take-home Messages IX. Conclusion Appendices: A: List of Participants B: Educational Tour Program E: Contents List of Informational Packages Provided to Delegates ACRONYMS ARFH Association for Reproductive and Family Health CBD Community-based Distributors/Distribution CPR Contraceptive Prevalence Rate CBD AGENT Community Reproductive Health Worker CTPH Conservation Through Public Health DDHS District Director of Health Services DMPA Depot-Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (Also called Depo-Provera) EH EngenderHealth FHI Family Health International FP Family Planning MIHV Minnesota Health Volunteers MOH Ministry of Health NGO Nongovernmental Organization RH Reproductive Health RHD Reproductive Health Division SC Save the Children TFR Total Fertility Rate USAID United States Agency for International Development I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Agenda An educational tour to Uganda on February 18–20 provided delegates from other countries with an introduction to the community-based distribution (CBD) of the injectable contraceptive DMPA (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, or Depo Provera). The goal was to learn about Uganda’s experiences with the CBD of DMPA and to forge relationships between the delegates so that they could exchange information about such programs in their home countries. -

Uganda FINAL 14.09.2010X

Skills for green jobs in Uganda Unedited background country study Countryside Innovations Network Ltd. ILO Skills and Employability Department 2010 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2010 First published 2010 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit http://www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data Skills for green jobs in Uganda : unedited background country study / International Labour Office, Skills and Employability Department. - Geneva: ILO, 2010 1 v. ISBN: 9789221239796 (web pdf) International Labour Office; Skills and Employability Dept skill / skill requirements / vocational training / training needs / green jobs / employment creation / climate change / environmental protection / Uganda 13.02.2 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

738-Noble Group of Institutions, Junagadh

A Global Country Study Report ON “BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES OF SPICES INDUSTRY UGANDA COUNTRY” Submitted to: Noble Group of Institutions, Junagadh IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT OF THE AWARD FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In Gujarat Technological University UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Prof. Riddhi Sanghvi Submitted by ENROLLMENT NAME OF STUDENT NUMBER 117380592001 Bhoomi Parmar 117380592002 Hemangi Pandya 117380592003 Makwana Rinkal 117380592004 Sohil Hirpara 117380592006 Karkar Ram 117380592007 Chintan Raval 117380592008 Gohil Ravindrasingh 117380592009 Pooja Nimavat 117380592010 Rashmita Patoliya 117380592012 Purti Daftary Batch: 2011-13, MBA SEMESTER III/IV Noble Group of Institutions, Junagadh MBA PROGRAMME Affiliated to Gujarat Technological University, Ahmedabad Declaration We, the undersigned Bhoomi Parmar, Hemangi Pandya, Pooja Nimavat, Rashmita Patoliya, Rinkal Patel, Purti Daftary, Chintan Raval, Sohel Hirpara, Ravindrasigh Gohel & Ram Karkar students of M.B.A. at Noble Group ofInstitutions, Junagadh, hereby declare that the report entitled ―Global Country Study Report for the MBA Degree is us original work and has been carried out under supervision &guidance of Prof. Riddhi Sanghvi. Place: Junagadh Date: 12/.4/2013 2 Preface India is growing fast as an industrial nation with the help of new technology, advance management, and advance knowledge of people. Now, people’s thoughts are changed and they turn to the management course. It is said, ―Without effective management and properplanning, not a single firm can run smoothly, effectively and efficiently ‖. Education is something which is not given in class rather; it is a process which can take place anytime and at any place. When any subject is taught theoretically in class it is known as Academic but when it is studied with the subject applicability in real life it is known as “Professional Education”.