Role of Media in Curbing Corruption: the Case of Uganda Under President Yoweri K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference of Central and East European Countries on Fighting Corruption

CONFERENCE OF CENTRAL AND EAST EUROPEAN COUNTRIES ON FIGHTING CORRUPTION International Co-operation: Its Role in Preventing and Combating Corruption and in the Creation of Regional Strategies Bucharest, March 30-31st UN Global Programme against Corruption Programme Manager: Dr. Petter Langseth International Cooperation Dr. Petter Langseth Its Role in Preventing and Combating Corruption and in the Creation of Regional Strategies SUMMARY1 According to CICP’s Global Programme against Corruption the purpose of a national anti-corruption programme is to:(i) increase the risk and cost of being corrupt and (ii) build integrity that changes the rules of the game and the behaviour of the players and (iii) eventually ensure the rule of law. Among the few success stories, Hong Kong, should have taught us that it takes time and considerable effort to curb corruption in a systemic corrupt environment. After more than 25 years Hong Kong is spending US$ 90 million (1998) per year and employed 1300 staff who conducted 2780 training sessions for the private and public sector. This is probably more than what all 50 African countries spent fighting corruption in 1999.2 Taking into account the increasing number of international instruments dealing with corruption, the workshop will be aimed at promoting co-ordinated efforts for the development of joint strategies for implementation of international instrument and best prevention practices at the international, national and municipal level. The anti-corruption strategy advocated in this paper rests on four pillars: (a) economic development; (b) democratic reform; (c) a strong civil society with access to information and a mandate to oversee the state; and (d) the presence of rule of law. -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

Uganda Police Force Anti - Corruption Strategy

UGANDA POLICE FORCE ANTI - CORRUPTION STRATEGY From Colonial Policing to Community Policing 2017/18-2021/22 Uganda Police Headquarters Naguru Plot 42/49, Katalima Road, P.o Box 7055, Kampala Uganda Fax: +256-414-343531/255630. General Lines: 256-414-343532/233814/231761/254033 Toll Free: 0800-199-699, 0800-199-499.Website: http://www.upf.go.ug Aligned to the JLOS Anti-corruption strategy With Support from Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................... 4 LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................ 6 CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND ........................................................ 8 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................... 8 With Support from 1.1 Situational analysis ..................................................................... 10 1.2 Definition of Corruption ............................................................. 12 1.3 The Police Mandate .................................................................... 15 1.4 Forms of corruption in the UPF .................................................. 16 1.5 Factors influencing corruption in UPF ........................................ 17 CHAPTER 2: EXISTING LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK TO FIGHT CORRUPTION IN UGANDA ................. 21 2.0 Introduction ................................................................................. 21 2.1 NRM Ten Point programme ...................................................... -

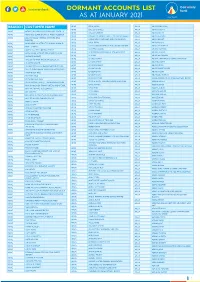

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Fighting Corruption in Uganda: Despite Small Gains, Citizens Pessimistic About Their Role

Dispatch No. 77 | 28 March 2016 Fighting corruption in Uganda: Despite small gains, citizens pessimistic about their role Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 77 | John Martin Kewaza Summary Uganda’s widespread corruption is highlighted in the country’s poor ranking (139th out of 167 countries) in the Corruption Perceptions Index as well as in the recent Africa edition of the Global Corruption Barometer (Transparency International, 2015a, b). Pernicious effects stretch from substandard public services through elections and the judiciary to stunted economic development. In 2012, four in 10 respondents (41%) in an Afrobarometer survey reported that they had been offered money or a gift in return for their votes during the 2011 elections. In petitioning Parliament last year to appoint a commission of inquiry, retired Supreme Court Judge Justice George Kanyeihamba said, “There is evidence of inefficiency, incompetence, and corruption in the judiciary and unethical conduct by members of the bar” (Parliament of Uganda, 2015). The Black Monday Movement, a coalition of anti- corruption civil society organisations, estimates that between 2000 and 2014, the government lost more than Shs. 24 trillion to corruption – enough to finance the country’s 2015/2016 budget (ActionAid Uganda, 2015) The government’s strategies to fight corruption include the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS), the Anti-Corruption Act, and the establishment of a specialized anti-corruption court within the judiciary. Internationally, Uganda has been a signatory of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) as well as the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption since 2004. Many civil society organisations have joined the anti-corruption fight, including the Anti- Corruption Coalition, Transparency International Uganda, the African Parliamentarians Network against Corruption, Civil Society Today, the Uganda Debt Network, and the NGO Forum (Martini, 2013). -

Genocide Or Just Another “Casualty of War”?: the Implications of the Memo Attributed to President Yoweri K

Genocide or Just Another “Casualty of War”?: The Implications of the Memo Attributed to President Yoweri K. Museveni of Uganda1 Todd David Whitmore University of Notre Dame n one occasion during the course of my fieldwork in Uganda, a person passed to me a document that purported to be a memo from Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni to Ohis brother Salim Saleh. The author of the memo refers to the Acholi people of northern Uganda as “Chimpanzees” and “Monkeys” and wants to “drastically reduce the population” so that he can obtain their abundant and fertile land (“I have now realized that the Monkeys called Acholis are sitting upon Gold Mine”). Given the potential importance of the memo, I had the document assessed as to its possible authenticity by two experts on Uganda’s political history and one scholar on African political leaders. Based on their judgments and further investigation of my own into the possible authenticity of the document, I have decided to make the memo public. It is available for viewing at musevenimemo.org. In the present article, I provide my own analysis of the memo. In the first major section of the article, I describe the context within which I received it. All documents have their social set- tings, and understanding those settings is important for interpreting the documents. The broader social context in which I received the memo is one of intrigue. Although I came to Uganda to study traditional Acholi culture and its interaction with Christianity (I am a theologian by train- ing), from the start I have been closely monitored and even followed by government operatives. -

Challenges of Development and Natural Resource Governance In

Ian Karusigarira Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival The road that the community expects to take in each generation is inspired and shaped by its memories of former heroic ages —Smith, D.A. (2009) Ian Karusigarira PhD Candidate, Graduate School of Global Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan Abstract In revolutionary political systems—such as Uganda’s—lies a strong collective memory that organizes and enforces national identity as a cultural property. National identity nurtured by the nexus between lived representations and narratives on collective memory of war, therefore, presents itself as a kind of politics with repetitive series of nation-state narratives, metaphorically suggesting how the putative qualities of the nation’s past reinforce the qualities of the present. This has two implications; it on one hand allows for changes in a narrative's cognitive claims which form core of its constitutive assumptions about the nation’s past. This past is collectively viewed as a fight against profanity and restoration of political sanctity; On the other hand, it subjects memory to new scientific heuristics involving its interpretations, transformation and distribution. I seek to interrogate the intricate memory entanglement in gaining and consolidating political power in Uganda. Of great importance are politics of remembering, forgetting and utter repudiation of memory of war while asserting control and restraint over who governs. The purpose of this paper is to understand and internalize the dynamics of how knowledge of the past relates with the present. This gives a precise definition of power in revolutionary-dominated regimes. Keywords: Memory of War, national narratives, victimhood, regime survival, Uganda ―75― 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示4.0国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja Uganda’s revolutionary memory, victimhood and regime survival 1. -

Fighting Corruption in Africa – a Comparative Study of Uganda and Botswana Dissertation

Fighting Corruption in Africa – A Comparative Study of Uganda and Botswana Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Verwaltungswissenschaften (Dr. rer. publ.) der Deutschen Hochschule für Verwaltungswissenschaften Speyer vorgelegt von: Stefan Ittner Speyer, 2009 Erstgutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. iur. Hans Herbert von Arnim, Dipl.-Volkswirt Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Sefik Alp Bahadir Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 18. März 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ___________________________________________ 4 I. INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________ 5 1. Object and Scope of Study ______________________________________________ 5 2. Structure of the Study_________________________________________________ 15 II. DEFINING CORRUPTION ______________________________________ 17 III. FIGHTING CORRUPTION ______________________________________ 26 1. Common Strategies Against Corruption__________________________________ 26 2. Criteria For Judging the Effectiveness of Anti-corruption Measures __________ 30 3. Difficulties in Fighting Corruption ______________________________________ 34 3.1 General Problems _________________________________________________________34 3.2 Specific Problems of Fighting Corruption in African Countries ______________________43 IV. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF ANTI-CORRUPTION STRATEGIES IN UGANDA AND BOTSWANA_____________________________________ 50 1. Historical Background and Determining Factors of Corruption ______________ 50 1.1 Country Profiles___________________________________________________________50 -

ABSTRACT YEMANE DESTA. Designing

ABSTRACT YEMANE DESTA. Designing Anti-Corruption Strategies for Developing Countries: A Country Study of Eritrea. (Under the direction of James H. Svara) The purpose of this research is to identify the anti-corruption strategies available for fighting corruption in developing countries and assess their relevance to the newly independent country of Eritrea by canvassing the opinions of Eritrean public officials. The anti-corruption strategies considered in the study are divided into four broad categories: Economic/Market Reforms, Administrative/Bureaucratic Reforms, Accountability/Transparency Enhancing Reforms, and Political Accountability Enhancing Reforms. Data are collected through the administration of questionnaires to a sample of 62 Eritrean public officials from 13 ministries of the Eritrean Government to assess their views regarding the extent, causes and remedies of corruption in Eritrea. The survey evidence indicates that the overwhelming majority (90 percent) of the respondents believe the issue of corruption in the context of Eritrean public administration is important. Moreover, an overwhelming majority (95 percent) of the respondents think that high emphasis should be given to preventing/fighting corruption at present. For the years 2000 and 2003 the majority (64.5 percent) of the respondents believe that corruption in Eritrea ranges between none to minimal while 35.5 percent think corruption in Eritrea ranges between moderate to prevalent. Two important differences are observed between respondents who perceive lower rates of corruption and those who perceive higher rates of corruption. The research indicates that respondents who have not received foreign education are more likely to perceive higher levels of corruption (38 percent) than respondents who received foreign education (18 percent). -

Special Sessions for Sexual and Gender Cases 788 Sexual and Gender Based Violence Cases Cleared in 40 Days

Issue 12 |January 2019 Special sessions for sexual and gender cases 788 Sexual and Gender Based Violence cases cleared in 40 days Key highlights for the 21st Annual Judges’ Ben Kiwanuka Memorial year 2018 Conference - Concept Lecture rekindles fond memories THROUGH THE LENS Top representatives of the Executive, Legislature and the Top representatives of the Executive, Legislature and the Judiciary at the 2018 Opening of the New Law Year event Judiciary at the 2018 Opening of the New Law Year event at the Judiciary headquarters in Kampala on January 29, at the Judiciary headquarters in Kampala on January 29, 2018. The event is a State function. 2018. The event is a State function. Justice and Constitutional Affairs Minister, Kahinda Otafiire, The Principal Judge, Dr. Yorokamu Bamwine, inspects an is joined by Justice, Law and Order Sector stakeholders at inmates’ food stall at Luzira Prison Complex during a hands- the commissioning of Mitooma Justice Centres on August 30, on Plea Bargain training on May 2, 2018. Looking on is the 2018. Commissioner (Custodial Sentences), Robert Munanura. High Court Judge (Judiciary Projects/Execution & Bailiffs Secretary to Judiciary, Kagole Expedito Kivumbi, in a Division), Gadenya Paul Wolimbwa, displays the Sudreau Global candid talk with Judiciary senior management staff during Justice Award 2018 that he received in recognition of his a team building exercise at the High Court Gardens in contribution to the Justice Sector in Uganda, June 21, 2018. Kampala on September 6, 2018. INSIDE. The best is yet to come 2 21st Annual Judges’ Conference - Concept 5 Judiciary highlights for the year 2018 20 788 cases cleared in 40-day SGBV sessions 25 Ben Kiwanuka Memorial Lecture rekindles he New Year is a time for looking back and for fond memories looking forward. -

Militarization in East Africa 2017

Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 1 SSHRC Partnership: Conjugal Slavery in Wartime Masculinities and Femininities Thematic Group Annotated Bibliography on Militarization of East Africa Aislinn Adams, Research Assistant Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 2 Table of Contents Statistics and Military Expenditure ...................................................................................... 7 World Bank. “Military Expenditure (% of GDP).” 1988-2015. ..................................................... 7 Military Budget. “Military Budget in Uganda.” 2001-2012. ........................................................... 7 World Bank. “Expenditure on education as % of total government expenditure (%).” 1999-2012. ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 World Bank. “Health expenditure, public (% of GDP).” 1995-2014. ............................................. 7 World Health Organization. “Uganda.” ......................................................................................... 7 - Total expenditure on health as % if GDP (2014): 7.2% ......................................................... 7 United Nations Development Programme. “Expenditure on health, total (% of GDP).” 2000- 2011. ................................................................................................................................................ 7 UN Data. “Country Profile: Uganda.” -

ICC-02/04-01/15-T-185-Red-ENG WT 22-10-2018 1/84 SZ T

ICC-02/04-01/15-T-185-Red-ENG WT 22-10-2018 1/84 SZ T Trial Hearing (Open Session) ICC-02/04-01/15 WITNESS: UGA-D26-P-0018 1 International Criminal Court 2 Trial Chamber IX 3 Situation: Republic of Uganda 4 In the case of The Prosecutor v. Dominic Ongwen - ICC-02/04-01/15 5 Presiding Judge Bertram Schmitt, Judge Péter Kovács and 6 Judge Raul Cano Pangalangan 7 Trial Hearing - Courtroom 3 8 Monday, 22 October 2018 9 (The hearing starts in open session at 9.31 a.m.) 10 THE COURT USHER: [9:31:53] All rise. 11 The International Criminal Court is now in session. 12 PRESIDING JUDGE SCHMITT: [9:32:11] Good morning, everyone. 13 Could the court officer please call the case. 14 THE COURT OFFICER: [9:32:21] Good morning, Mr President, your Honours. 15 The situation in the Republic of Uganda, in the case of The Prosecutor versus 16 Dominic Ongwen, case reference ICC-02/04-01/15. 17 And for the record, we are in open session. 18 PRESIDING JUDGE SCHMITT: [9:32:35] Thank you. 19 I ask for the appearances of the parties. Mr Gumpert, for the Prosecution first, 20 please. 21 MR GUMPERT: [9:32:42] Good morning, your Honours. Ben Gumpert for the 22 Prosecution. With me today, Pubudu Sachithanandan, Adesola Adeboyejo, 23 Colleen Gilg, Julian Elderfield, Hai Do Duc, Jasmine Suljanovic, Grace Goh, and I'm 24 very sorry to say that I have made inadequate preparation with the regard to the lady 25 who sits at the back of the court.