Freedom Subject to Licence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

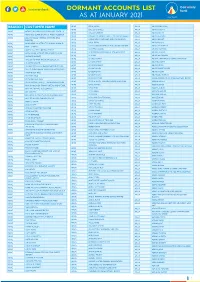

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Role of Media in Curbing Corruption: the Case of Uganda Under President Yoweri K

Economic & Social Affairs DESA Working Paper No. 72 ST/ESA/2009/DWP/72 January 2009 Role of media in curbing corruption: the case of Uganda under President Yoweri K. Museveni during the “no-party” system Monica Nogara Abstract Free, independent and hard-hitting media can play an important role in curbing corruption. Media in Uganda has enjoyed considerable freedom in this regard since Museveni came to power in 1986. The evolving power structure and a changing media landscape, however, have presented both challenges and opportunities for media’s watchdog role on corruption. This paper will explore how this environment defined such role between 1986 and 2006 during Museveni’s “no-party” rule. It argues that, although media won important battles to promote accountability in public offices, the regime’s complex power structure has consistently challenged their role as an instrument of public accountability. JEL Classification: D72, D73, D81, D82, D83, H11, K40, L82 Keywords: corruption, media, press freedom, governance, rule of law Monica Nogara is currently Economic Affairs Officer in the Office for ECOSOC Support and Coordination. E-mail: [email protected] Comments should be addressed by email to the author. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 The role of media in curbing corruption ............................................................................. 2 The case of Uganda under President Yoweri K. Museveni ............................................................ -

An Investment Guide to Uganda

UNITED NATIONS International Chamber of Commerce The world business organization AN INVESTMENT GUIDE TO UGANDA Opportunities and conditions March 2004 UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2004 ii UNCTAD The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) was established in 1964 as a per- manent intergovernmental body. Its main goals are to maximize the trade, investment and development opportunities of developing countries, to help them face challenges arising from globalization, and to help them integrate into the world economy on an equitable basis. UNCTAD’s membership comprises 192 States. Its secretariat is located in Geneva, Switzerland, and forms part of the United Nations Secretariat. ICC The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) is the world business organization. It is the only body that speaks with authority on behalf of enterprises from all sectors in every part of the world, grouping together thousands of members, companies and associations from 130 countries. ICC promotes an open international trade and investment system and the market economy in the context of sustainable growth and development. It makes rules that govern the conduct of business across borders. Within a year of the creation of the United Nations it was granted consultative status at the highest level (category A) with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. This is now known as General Category consulta- tive status. Note The term “country” as used in this study also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas; the designa- tions employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatso- ever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Vote: 504 Bugiri District Structure of Workplan

Local Government Workplan Vote: 504 Bugiri District Structure of Workplan Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 D: Details of Annual Workplan Activities and Expenditures for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Workplan Vote: 504 Bugiri District Foreword It is with great pleasure that I present the Annual Workplan and Budget for Bugiri District Local Government for the Financial Year 2014-2015. The Budget Estimates have been prepared in fulfilment of the Local Government Act 1997, Section 78 (1) that mandates Local Governments to formulate, approve and execute their budgets and workplans provided the budgets are balanced. The theme of this Financial Years's Budget Estimates is to consolidate our program achievements that address increased productivity, improved health, household incomes, education and improved access to social infrastructure so as to achieve prosperity for all for the people of Bugiri District. The Budget provides for resources ear marked for the provision of basic public goods and services especially in the most prioritized sectors of Health, Education, Roads, and Production to improve incomes of the people in the district. The budget estimates have been prepared in an all inclusive manner and I take this opportunity to convey my sincere gratitude to all stakeholders who have participated in the process of formulating these estimates of revenue and expenditure; the technical staff in the district, NGOs, Donors and other partners in development. I wish to extend my Special thanks to the Government of Uganda and the Ministry of Local Government for the support provided through the DLSP and CAIIP-3 programme to District which focus on improving livelihoods of the people in Bugiri. -

A Media Minefield RIGHTS Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda WATCH

Uganda HUMAN A Media Minefield RIGHTS Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda WATCH A Media Minefield Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-627-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2010 1-56432-627-6 A Media Minefield Increased Threats to Freedom of Expression in Uganda I. Map of Uganda ......................................................................................................................... 1 II. Summary ................................................................................................................................. 2 III. Recommendations ................................................................................................................ -

Violence Instead of Vigilance RIGHTS Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’S Rapid Response Unit WATCH

Uganda HUMAN Violence Instead of Vigilance RIGHTS Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit WATCH Violence Instead of Vigilance Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-750-7 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org March 2011 ISBN 1-56432-750-7 Violence Instead of Vigilance Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 6 To the President and Government of Uganda .................................................................. 6 To the Uganda Police Force, Particularly the Police Standards Unit and the Criminal Investigations Department of Police ................................................................. -

Uganda - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 9 October 2009

Uganda - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 9 October 2009 Information on the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) and treatment of those who are members or are perceived to be members of the FDC by the government and/or society. Are there any reports of FDC members being kept in detention or put under house arrest during March-April this year? An Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada response to a request for information on the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) states: “Various sources reported that the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) was established in 2004 as a result of a union between opposition parties the Reform Agenda, the Parliamentary Advocacy Forum, and the National Democratic Forum (Political Parties of the World 2005, 602; Europa World Year Book 2005 2005, 4386; Political Handbook of the World 2005-2006 2005, 1211). The FDC claims to be a "'strong, democratic, mass organization'" (ibid.), and has reportedly attracted a number of members of parliament (MPs) from the Democratic Party (DP) and Uganda People's Congress (UPC) to its organization.” (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (23 February 2006) UGA100952.E – Uganda: The Forum for Democratic Change (FDC); its structure, platform, leadership and executive members; and treatment of its members by authorities (2005 - January 2006)) In a section titled “Presidential, 1.Parliamentary and Local Council elections March 2006” a document published by the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) states: “The FDC presented Col. Dr Kizza Besigye as its Presidential candidate in an election which was marred by intimidation, bribery, and harassment. -

Integrated Water Management and Development Project

SFG3693 V1 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Republic of Uganda MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT Public Disclosure Authorized INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION PROJECT IN MAJANJI, LUMINO, BUHEHE, MASAFU, MASABA, DABANI, BUTEBA, MASINYA and SIKUDA SUB-COUNTIES; BUSIA MUNICIPALITY, BUSIA DISTRICT. Public Disclosure Authorized UPADTED AND FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized APRIL 2018 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for Busia Water Supply and Sanitation Project TABLE OF CONTENTS table of contents .........................................................................................................................................................................................................ii LIST OF FIGURES.................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF PLATES.....................................................................................................................................................................................................viii 1ACRONYMSINTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................................................................................ix -

Acase for Kyadondo East Constituency

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 6 ~ Issue 10 (2018) pp.: 59-85 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Power And Individual Merit In Multiparty Despensation In Uganda: Acase For Kyadondo East Constituency Nabukeera Madinah* Lecturer Kyambogo University Faculty of Arts and Social Science Department of History and Political Science ABSTRACT:There is a growing tendency of individual politics in Uganda during multiparty dispensation. Individual candidates have continued to win elections at the grass root where there is stiff competition among parties. This paper assesses a case study of Kyadondo East Constituency Member of Parliamentary seat that became vacant in April, 2017 to understand the dynamics of the growing individualism in party politics in Uganda. This paper assessesthe lived experience of an independent candidate, factors explaining his win, factors behind the growth of individual politics in Uganda. Using documentary review, tweets andinterviews, the findings indicate the rise of individual merit under multi-party politics in Uganda and that, independents in parliament who still have allegiance to partieshave selfish interest,they are given money to compete, support and stay within the party. Those interested in the party, is because of the favors which arenot sustainable in the long run. Received 17 October, 2018; Accepted 03 Novenber, 2018 © The author(s) 2018. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. INTRODUCTION Individual merit has over the years seen to overtake party politics during multiparty dispensation in Uganda given the increasing number of independent candidates in the parliament of Uganda.Individual candidates have continued to win elections at the grass root where there is stiff competition among parties. -

Uganda - Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 27 January 2010

Uganda - Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 27 January 2010 Treatment of members of the FDC in Uganda A January 2010 news article from The Daily Monitor newspaper under the heading Kampala , states: Forum for Democratic Change has completed its nomination exercise for the party s flag bearer for 2011 general elections, with a call on the Police chief to provide security to candidates as they traverse the country for votes. The two-day nomination exercise ended on Wednesday with two candidates, Dr Kizza Besigye and Maj. Gen. Mugisha Muntu getting nominated. (The Daily Monitor (15 January 2010) FDC calls for Police protection as vote-searching kicks off) The same article under the heading Campaign programmes , continues: We shall officially write to the Inspector General of Police and give him our campaign programmes, said Mr Dan Mugarura, the party s electoral commission chief. We shall ask them to give us security, although sometimes we ask for security and they give us insecurity. We hope that they will respect our gatherings and meetings, he said. FDC deputy electoral commissioner Micheal Kabaziguruka said the nomination exercise was free and fair and that they expect all the candidates to conduct themselves according to the party s established guidelines. He warned that candidates could face expulsion or pay heavy fines if they fail to maintain sanity during the campaign. Gen. Muntu attended the meeting while Dr Besigye was represented by his political assistant, Mr Sam Mugumya. (ibid) Under the heading Freedom of Assembly and Expression , the January 2010 Human Rights Watch report on Events of 2009 in Uganda, states: In August police beat and detained members of the opposition, Forum for Democratic Change, who were demonstrating in Kampala against extensions of office terms for the chairman and commissioners of the Electoral Commission, despite accusations of election malpractice. -

SADEV Report 2009:3.1 Uganda

Party Cooperation in a Results Perspective Country Study: Uganda n SADEV 2009:3.1 REPORT Swedish Agency for Development Evaluation P. O. Box 1902, SE-651 19 Karlstad, Sweden SADEV REPORT 2009:3.1 Party Cooperation in a Results Perspective Country Study: Uganda Authors: Eva-Marie Kjellström, Sabiti Makara and Peter Sjöberg Copyright: SADEV SADEV Reports are available at www.sadev.se Printed in Karlstad, Sweden 2010 ISSN 1653-9249 ISBN 978-91-85679-18-8 PARTY COOPERATION IN A RESULTS PERSPECTIVE INTRODUCTION Acronyms CIL Change Initiative Limited CIS Center Party International Foundation/Centerpartiets Internationella Stiftelse CP Conservative Party DDP Deepening Democracy Programme DP Democratic Party FDC Forum for Democratic Change FES Friedrich Ebert Stiftung IDEA Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance IPC Inter-party cooperation IPA Inter-party alliance IRI International Republican Institute JEEMA Justice Forum JHS Jarl Hjalmarson Foundation/Jarl Hjalmarson Stiftelsen KAS Konrad Adenauer Stiftung KIC Christian Democratic International Centre/Kristdemokratiskt Internationellt Centrum NDC National Delegates Conference NDI National Democratic Institute NGO Non Governmental Organisation NIMD Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy NRM National Resistance Movement PAO Party Affiliated Organisation PPP People’s Progressive Party RYPLA Regional Young Political Leadership Academy Sida Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency Silc Swedish International Liberal Centre 1 PARTY COOPERATION IN A RESULTS PERSPECTIVE INTRODUCTION -

Violence Instead of Vigilance RIGHTS Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’S Rapid Response Unit WATCH

Uganda HUMAN Violence Instead of Vigilance RIGHTS Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit WATCH Violence Instead of Vigilance Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-750-7 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org March 2011 ISBN 1-56432-750-7 Violence Instead of Vigilance Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 6 To the President and Government of Uganda .................................................................. 6 To the Uganda Police Force, Particularly the Police Standards Unit and the Criminal Investigations Department of Police .................................................................