An Investment Guide to Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Finance for Energy Access in Uganda

DIGITAL FINANCE FOR ENERGY ACCESS IN UGANDA: PUTTING MOBILE MONEY BIG DATA ANALYTICS TO WORK Mayank Jain, Robin Gravesteijn, Arne Jacobson, Emily Gamble, Nicola Scarrone ABSTRACT Access to clean energy is a basic need that directly supports people’s livelihood, yet more than 30 million Ugandans live without electricity. Pay-as-you-go (PayGo) is a promising and innovative financing solution that can make clean energy affordable for low-income people. However, there remains significant knowledge gaps regarding the digital energy finance market’s size, outreach, growth and impact. This study leverages anonymized mobile money data of PayGo solar energy users in Uganda to gain insight on digital energy financing in Uganda. It also draws from a customer phone survey that assesses solar product adoption and quality of life improvements. We find that the Uganda solar market is growing rapidly and currently has around one million active customers. Around 12 percent of the Ugandan households own a solar home system and there is opportunity for further market expansion, especially in areas with high levels of mobile money penetration. The clean energy market is becoming more inter-connected with the digital finance market. In fact, digital energy financing through PayGo has promoted wider financial inclusion around 110,000 new mobile money customers. Likewise, when Uganda’s implemented a temporary mobile money tax it caused an immediate slow-down in PayGo uptake and new mobile money activations indicating it negatively impacted the country’s access to clean energy and formal finance. The customer survey result indicates that poorer customers seem equally able to purchase larger solar systems as compared to richer customers because of mobile money financing. -

Elite Strategies and Contested Dominance in Kampala

ESID Working Paper No. 146 Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala Nansozi K. Muwanga1, Paul I. Mukwaya2 and Tom Goodfellow3 June 2020 1 Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected]. 3 Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield, UK Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-56-9 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala. Abstract Although Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) has dominated Uganda’s political scene for over three decades, the capital Kampala refuses to submit to the NRM’s grip. As opposition activism in the city has become increasingly explosive, the ruling elite has developed a widening range of strategies to try and win urban support and constrain opposition. In this paper, we subject the NRM’s strategies over the decade 2010-2020 to close scrutiny. We explore elite strategies pursued both from the ‘top down’, through legal and administrative manoeuvres and a ramping up of violent coercion, and from the ‘bottom up’, through attempts to build support among urban youth and infiltrate organisations in the urban informal transport sector. Although this evolving suite of strategies and tactics has met with some success in specific places and times, opposition has constantly resurfaced. -

An Investigation of the Effects of Barley Cultivation On

© COPYRIGHT by Cleo Roberts 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BREWING SUCCESS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE EFFECTS OF BARLEY CULTIVATION ON SMALL HOLDER FARMERS IN EASTERN UGANDA BY Cleo Roberts ABSTRACT As Nile Breweries and Uganda Breweries have begun purchasing barley from Ugandan farmers, they have insisted that their sales support economic development in the country. While these breweries' competition for raw materials has the potential to provide smallholder barley farmers with increased income and access to credit, it may also encourage alcohol consumption and exacerbate environmental degradation. This paper explores whether and in what ways barley farmers in Kapchorwa, Bukwa, and Kween Districts, in eastern Uganda, benefit from selling their produce to Nile Breweries and Uganda Breweries. It pays particular attention to the breweries' intended effects on respondents' incomes, expenditures, and access to credit, as well as the potential unintended consequences of barley production on respondents' alcohol consumption and environmental stewardship. The author relies both on narratives and on econometric analysis to draw conclusions about the effect of breweries' demand for raw materials on domestic small-holders. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Infinite thanks to Peter Redvers-Lee and Kenneth Muhinda, without whose invaluable assistance and guidance this study could not have taken place; to Gavin Van Wijk, who provided access to essential contacts and information; to George Mbogo and Joseph Kalule who facilitated travel to and research in various regions -

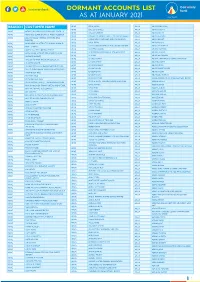

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Draft Non Motorised Transport Policy

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Ministry of Works and Transport DRAFT NON MOTORISED TRANSPORT POLICY October 2012 NON MOTORISED TRANSPORT POLICY Table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations............................................................................................iv Glossary and Definitions...................................................................................................v Executive Summary...........................................................................................................vi Foreword............................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................3 2 Analysis of Current situation..........................................................................................4 2.1. ‘Universal design’ principles..................................................................................4 2.2. Road maintenance...................................................................................................4 2.3. Road traffic: hierarchy of presumed ‘rights’...........................................................4 2.4. National roads..........................................................................................................4 2.5. District and community roads..................................................................................7 2.6. Urban roads..............................................................................................................7 -

Mgm-Jun08.Pdf

Contents THE FEEDBACK FOR THE MADHVANI FOUNDATION Editor’s Note 2 A dedicated website was part of the launch for the 2008 / 2009 Madhvani Foundation scholarship program. The Pan Floor at Kakira Sugar Works 4 www.madhvanifoundation.com Kakira the Responsible Employer 5 The site registered 137,315 hits in its first three weeks and 3,951 Application ormsF were downloaded. The site also enables graduates who have been sponsored by the Madhvani Foundation to have their CV’s hosted so that potential Recognising the Contribution of Kakira’s Cane Cutters 6 employers can have a look; underpinning the belief of the Foundation that our responsibility doesn’t just end at Mweya & Paraa Attend the SKAL Gala Evening 8 educating less fortunate Ugandans but also to try and give them a helping hand so that they may embark on the journey of life by obtaining employment. Chobe Safari Lodge A Landmark Destination Being Created 9 Below are a selection of some of the feedback received by visitors to the site : Madhvani Foundation 2008/09 Scholarship Scheme 10 Kakira Hospital - Providing a Service to the Community 12 BAGABO RASHID JOSEPH OKELLO EADL New Brand Identity, New Horizons 13 I am glad that you gave us this chance as this is good for us who cannot afford all the tuition at campus and really do not want The Madhvani Foundation is extremely commendable in terms Madhvani Group Exploring Opportunities in India 14 to miss this opportunity. Thank you Madhvani Foundation of its activities and the quantum of contribution to Uganda. I hope others can emulate this most noble act Madhvani Group Invests in Uganda’s Future 15 NSUBUGA BRIAN Group News Pictorial 16 SAM in London Anybody who promotes education is the only person causing Mweya & Paraa Safari Lodges Invests in Human Assets 20 development from the left ventricle of the heart where the force Well done Muljibhai Madhvani Foundation. -

Report on the Implementation of the Investment Policy Review Uganda

Report on the Implementation of the Investment Policy Review Uganda United Nations Conference on Trade and Development REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INVESTMENT POLICY REVIEW UGANDA UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2007 Report on the Implementation of the Investment Policy Review Uganda Note UNCTAD serves as the focal point within the United Nations Secretariat for all matters related to foreign direct investment. This function was formerly carried out by the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations (1975-1992). UNCTAD's work is carried out through intergovernmental deliberations, research and analysis, technical assistance activities, seminars, workshops and conferences. The term "country" as used in this study also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas; the designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. In addition, the designations of country groups are intended solely for statistical or analytical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage of develop- ment reached by a particular country or area in the development process. The following symbols have been used in the tables: • Two dots (..) indicate that date are not available or not separately re- ported. Rows in tables have been omitted in those cases where no data are available for any of the elements in the row. • A dash (-) indicates that the item is equal to zero or its value is negligible. -

Agent Banking Faqs

Agent Banking Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is agent banking? An arrangement that allows a retail outlet serve as representative of the agent offering transactional services to the bank customers as defined by agency banking guidelines. 2. Where can I conduct agent banking transactions? You can perform your banking transactions at any agent in Uganda which has Agent Banking Company handshake Logo (black & green) available at the agent premises. 3. Where do I find the Standard Chartered authorised agents? The authorised Standard Chartered agents can be found at the locations below. No AGENT OUTLET NAME PHYSICAL OUTLET ADDRESS 1 Shell Namugongo Along Namugongo Road formerly Super oil Petrol Station 2 Shell Rubaga Road Along Rubaga Road 3 Shell Makerere Makerere - Bwaise Road, Opposite Eastern Gate 4 Shell Makindye Makindye- Opposite Military Barracks 5 Shell Muyenga Muyenga - Kibuli Road Towards Kabalagala 6 Shell Kansanga Kansanga - Next to Former Didi's World 7 Shell Najjanakumbi Entebbe Road - Opposite Kenjoy Supermarket 8 Shell Kampala Road Kampala Road before Commercial Plaza 9 Shell Portbell Portbell Road Adjacent to Silver Springs Hotel 10 Shell Kabowa Ndeeba, Nyanama Road 4. What should I do to become a Standard Chartered Approved Agent Visit any of the Standard Chartered branches to be provided the details of the requirements to become an Agent. 5. What types of transactions can I perform? As a Standard Charted Bank Uganda customer, you can conduct the following; a) cash deposit b) cash withdrawal 6. In which currency can I transact? You will only be allowed to perform cash withdrawal and cash deposit transactions in Uganda Shillings. -

AT JINJA CIVIL REGISTRY CAUSELIST for the SITTINGS of : 01-10-2018 to 05-10-2018

10/2/2018 Court Case Administration System THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA(HCT) AT JINJA CIVIL REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 01-10-2018 to 05-10-2018 MONDAY, 01- OCT-2018 HON. LADY JUSTICE BEFORE:: COURT ROOM :: COURT 1 EVA K. LUSWATA Case Case Sing Time Pares Claim Posion number Category Type WAIDHA WILSON AND HCT-03- MUTAASA EDWARD VS Hearing CV-MA- Miscellaneous PENDING 1. 09:30 BUYENDE DISTRICT LOCAL A TEMPORARY INJUNCTION applicant's 0100- Applicaon HEARING GOVERNMENT AND case 2017 ANOPTHER HON. MR JUSTICE BEFORE:: COURT ROOM :: COURT 2 MICHAEL ELUBU Case Case Sing Time Pares Claim Posion number Category Type HCT-03- IGANGA TALKIES LTD VS Hearing - CV-CS- PENDING 1. 09:00 Civil Suits DAMBA STEPHEN & PLAINT Plainff's 0101- HEARING OTHERS case 2014 HCT-03- KIIRYA GORDON WILSON Hearing - CV-CS- VS NAMUTUMBA SPECIAL DAMAGES,GENERAL DAMAGES, PENDING 2. 09:00 Civil Suits Plainff's 0021- DISTRICT LOCAL COSTS AND INTERESTS HEARING case 2017 GOVERNMENT HCT-03- Hearing - CV-CS- JOHN OKWARE VS YOUSA PENDING 3. 09:00 Civil Suits RECOVERY OF LAND. Plainff's 0103- KHAN & 4 OTHERS. HEARING case 2014 ABUNDANT LIFE CAMP HCT-03- LTD VS WAIRAKA Hearing - CV-CS- RECOVERY SHS 305,000,000/= PENDING 4. 09:00 Civil Suits COMMUNITY Plainff's 0099- ,GENERAL DAMAGES & HEARING ASSOCIATION LTD & 6 case 2015 OTHERS DEPUTY REGISTRAR BEFORE:: BYARUHANGA JESSE COURT ROOM :: CHAMBER C RUGYEMA Case Case Sing Time Pares Claim Posion number Category Type HCT-03- CV-MA- Miscellaneous MATOVU STEPHEN VS PENDING 1. -

LG Budget Estimates 201213 Wakiso.Pdf

Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District Structure of Budget Estimates A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue C: Detailed Estimates of Expenditure D: Status of Arrears Page 1 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Revenue Performance and Plans 2011/12 2012/13 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget June UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 3,737,767 3,177,703 7,413,823 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 5,373,311 4,952,624 5,648,166 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 28,713,079 27,512,936 32,601,298 2c. Other Government Transfers 6,853,215 4,532,570 10,697,450 3. Local Development Grant 1,757,586 1,949,046 1,756,183 Total Revenues 46,434,958 42,124,880 58,116,921 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2011/12 2012/13 Approved Budget Actual Approved Budget Expenditure by UShs 000's end of June 1a Administration 1,427,411 1,331,440 3,894,714 1b Multi-sectoral Transfers to LLGs 5,459,820 4,818,229 0 2 Finance 679,520 658,550 2,623,938 3 Statutory Bodies 1,017,337 885,126 1,981,617 4 Production and Marketing 3,060,260 3,015,477 3,522,157 5 Health 4,877,837 4,807,510 6,201,655 6 Education 21,144,765 19,753,179 24,948,712 7a Roads and Engineering 6,161,280 4,538,877 11,151,699 7b Water 802,836 631,193 1,063,321 8 Natural Resources 427,251 238,655 659,113 9 Community Based Services 610,472 678,202 1,175,071 10 Planning 630,334 302,574 560,032 11 Internal Audit 135,835 117,414 334,893 Grand Total 46,434,958 41,776,425 58,116,922 Wage Rec't: 22,456,951 21,702,872 24,924,778 Non Wage Rec't: 16,062,717 13,930,979 23,191,011 Domestic Dev't 7,915,291 6,142,574 10,001,133 Donor Dev't 0 0 0 Page 2 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue 2011/12 2012/13 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget of June UShs 000's 1. -

Role of Media in Curbing Corruption: the Case of Uganda Under President Yoweri K

Economic & Social Affairs DESA Working Paper No. 72 ST/ESA/2009/DWP/72 January 2009 Role of media in curbing corruption: the case of Uganda under President Yoweri K. Museveni during the “no-party” system Monica Nogara Abstract Free, independent and hard-hitting media can play an important role in curbing corruption. Media in Uganda has enjoyed considerable freedom in this regard since Museveni came to power in 1986. The evolving power structure and a changing media landscape, however, have presented both challenges and opportunities for media’s watchdog role on corruption. This paper will explore how this environment defined such role between 1986 and 2006 during Museveni’s “no-party” rule. It argues that, although media won important battles to promote accountability in public offices, the regime’s complex power structure has consistently challenged their role as an instrument of public accountability. JEL Classification: D72, D73, D81, D82, D83, H11, K40, L82 Keywords: corruption, media, press freedom, governance, rule of law Monica Nogara is currently Economic Affairs Officer in the Office for ECOSOC Support and Coordination. E-mail: [email protected] Comments should be addressed by email to the author. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 The role of media in curbing corruption ............................................................................. 2 The case of Uganda under President Yoweri K. Museveni ............................................................ -

8. UNENDING LIFE the Term Unending Life Refers to Eternity Which Means Everlasting Life

8. UNENDING LIFE The term unending life refers to eternity which means everlasting life. Therefore, unending life means that people continue to live in another form even after their death. After death the body decomposes but the soul continues to live because it goes to live in another world (spiritual world) Death is a transition from the physical world(life) to a spiritual world. To some people death is un kind and taken to be a curse while to others death is positive and a route to eternal happiness. To scientists, death is the end of life while in religion it is a process to another life. People believe that the dead go to hell or heaven depending on how they have lived on earth. Young people think less about death until someone close to them dies. Many people question the existence of God and the life to come. This is due to scientific theories which oppose the existence of God. So, they reject issues about life after death basing on what they see, hear and what they learn. REASONS FOR DOUBTING LIFE AFTER DEATH. Confusing explanation given by different religions; Some people say that life after death is just a religious theory explained by different religions. Each religion has its own way of explaining this theory which brings doubt among people. It contradicts with science; Science proves that death is the end of everything and that is why the educated have opposed life after death. Scientific research has shown that life stops when a person dies. Modernity declares it ancient; Modern society looks at believing in eternal life as an outdated fact of the ancient people who lacked the scientific approach towards life.