Portrait of a Failed Rebellion: an Account of Rational, Sub-Optimal Violence in Western Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing the Self on Survivor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository TEMPORARILY MACHIAVELLIAN: PERFORMING THE SELF ON SURVIVOR An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by REBECCA J. ROBERTS Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. James Ball III May 2018 Major: Performance Studies Psychology TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTERS I. OUTWIT. OUTPLAY. OUTLAST ......................................................................... 8 History of Survivor ............................................................................................ 8 Origin Story of Survivor .................................................................................. 10 Becoming the Sole Survivor ............................................................................ 12 II. IDENTITY & SELF-PRESENTATION ................................................................ 17 Role Performance ........................................................................................... -

Vulnerable and Marginalized Groups Framework (Vmgf)

VULNERABLE AND MARGINALIZED GROUPS FRAMEWORK (VMGF) FOR THE UGANDA DIGITAL ACCELERATION PROGRAM [UDAP] FPIC with The Tepeth Community in Tapac FPIC with the Batwa Community in Bundibugyo MARCH 2021 Confidential VULNERABLEV ANDULNE MARGINALISEDRABLE AND MA GROUPSRGINALIZ FRAMEWORKED GROUPS (VMGF) January 2021 2 FRAMEWORK Action Parties Designation Signature Prepared Chris OPESEN & Derrick Social Scientist & Environmental KYATEREKERA Specialist Reviewed Flavia OPIO Business Analyst Approved Vivian DDAMBYA Director Technical Services DOCUMENT NUMBER: NITA-U/2021/PLN THE NATIONAL INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY, UGANDA (NITA-U) Palm Courts; Plot 7A Rotary Avenue (Former Lugogo Bypass). P.O. Box 33151, Kampala- Uganda Tel: +256-417-801041/2, Fax: +256-417-801050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nita.go.ug The Uganda Digital Acceleration Program [UDAP) Page iii Confidential VULNERABLEV ANDULNE MARGINALISEDRABLE AND MA GROUPSRGINALIZ FRAMEWORKED GROUPS (VMGF) January 2021 2 FRAMEWORK TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS........................................................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Background................................................................................................................................................. -

Access to Resources and Predictability in Armed Rebellion: the FAPC’S Short-Lived “Monaco” in Eastern Congo Kristof Titeca

● ● ● ● Africa Spectrum 2/2011: 43-70 Access to Resources and Predictability in Armed Rebellion: The FAPC’s Short-lived “Monaco” in Eastern Congo Kristof Titeca Abstract: This article discusses the impact of economic resources on the behaviour of an armed group. The availability of resources, and the presence of “lootable” resources in particular, is presumed to have a negative impact on the way an armed group behaves toward the civilian population. The case of the Armed Forces of the Congolese People (Forces Armées du Peuple Congolais, FAPC) in eastern Congo strongly suggests that it is necessary to look beyond this monocausal argument so as to witness the range of other factors at work. In this vein, first, the article demonstrates how the political economy literature underestimates the ease of accessibility of lootable resources. The paper then shows how the behaviour of this armed group was tied to a particular economic interest: In order to access these lootable goods, the FAPC was dependent on pre-established trading networks, so it had to increase the predictability of economic interactions through the construction of a minimum of social and economic order. Second, the article reveals how the political economy literature can underestimate the specific conflict dynamics. Military security in particular has a strong impact in this context. Manuscript received 3 August 2011; accepted 11 October 2011 Keywords: Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda, armed con- flicts, armed forces/military units, informal cross-border trade Kristof Titeca is a postdoctoral fellow from the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO), based at the Institute of Development Policy and Man- agement, University of Antwerp. -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Rebellion and God's Judgment in the Book of Jude

________________________________________________________________________________ BIBLIOTHECA SACRA 170 (October–December 2013): 454–77 REBELLION AND GOD’S JUDGMENT IN THE BOOK OF JUDE Herbert W. Bateman IV UDE’S SHORT LETTER, tucked away at the end of the New Tes- tament, offers a straightforward theological point frequently J overlooked, yet pertinent to both his and the present time.1 Writing with a sense of urgency (v. 3),2 Jude tackled directly the issue of rebellion and the subsequent outcome for anyone who re- bels against God. Jude’s theological concern about rebellion and its Herbert W. Bateman is an author and teacher who resides in Leesburg, Indiana. 1 Several reasons suggest why Jude’s epistle tends to be overlooked. First, Jude’s insulting tone (vv. 8–16) and his evident displeasure over the godless when he de- clared, “Damnation to them” (oujai; aujtoi'", v. 11) can be unsettling. Second, words interwoven in the letter like “I keep” (thvrew, vv. 1, 6, 13, 21) and “immorality” (ajsevlgeia, v. 4; ejkporneuvsw, v. 7) are finely nuanced and important for understand- ing Jude’s argument. His ambiguous use of “ungodly” (ajsebei'") and “these people” (ou|toi, vv. 8, 10, 12, 16, 19) is difficult to apply to twenty-first-century believers. Third, Jude’s references to Old Testament situations (e.g., Exodus generation, an- gels, and Gentile urbanites, vv. 5–7) as well as Old Testament people (e.g., Cain, Korah, Balaam, v. 11) and his application of them to his generation may seem for- eign. Fourth, including nonbiblical material like 1 Enoch (vv. 14–15) and The As- sumption (Testament) of Moses (v. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

NAT TURNER's REVOLT: REBELLION and RESPONSE in SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory

NAT TURNER’S REVOLT: REBELLION AND RESPONSE IN SOUTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA by PATRICK H. BREEN (Under the Direction of Emory M. Thomas) ABSTRACT In 1831, Nat Turner led a revolt in Southampton County, Virginia. The revolt itself lasted little more than a day before it was suppressed by whites from the area. Many people died during the revolt, including the largest number of white casualties in any single slave revolt in the history of the United States. After the revolt was suppressed, Nat Turner himself remained at-large for more than two months. When he was captured, Nat Turner was interviewed by whites and this confession was eventually published by a local lawyer, Thomas R. Gray. Because of the number of whites killed and the remarkable nature of the Confessions, the revolt has remained the most prominent revolt in American history. Despite the prominence of the revolt, no full length critical history of the revolt has been written since 1937. This dissertation presents a new history of the revolt, paying careful attention to the dynamic of the revolt itself and what the revolt suggests about authority and power in Southampton County. The revolt was a challenge to the power of the slaveholders, but the crisis that ensued revealed many other deep divisions within Southampton’s society. Rebels who challenged white authority did not win universal support from the local slaves, suggesting that disagreements within the black community existed about how they should respond to the oppression of slavery. At the same time, the crisis following the rebellion revealed divisions within white society. -

A Case of Bundibugyo District, Uganda

Health, 2019, 11, 108-128 http://www.scirp.org/journal/health ISSN Online: 1949-5005 ISSN Print: 1949-4998 Social Dynamics of Ebola Virus Disease: A Case of Bundibugyo District, Uganda Clovice Kankya1,2*#, Daisy Nabadda1,2#, Consolata Kabonesa2, Luke Nyakarahuka1, James Muleme1, Samuel Okware3, Richard Asaba2 1Department of Biosecurity, Ecosystems and Veterinary Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Resources and Biosecurity (COVAB), Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 2Department of Gender, School of Women and Gender Studies, College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHUSS), Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 3Uganda National Health Research Organization, Entebbe, Uganda How to cite this paper: Kankya, C., Na- Abstract badda, D., Kabonesa, C., Nyakarahuka, L., Muleme, J., Okware, S. and Asaba, R. Background: Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) presents with a high global mortal- (2019) Social Dynamics of Ebola Virus ity and is known to be a highly infectious disease with devastating and gen- Disease: A Case of Bundibugyo District, dered effects on the social fabric, yet most of the science has focused on the Uganda. Health, 11, 108-128. disease’s biology. However, little has been documented with regard to the https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2019.111011 gender and social aspects of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in two sub counties Received: December 23, 2018 (Kikyo and Bundibugyo Town Council) in Bundibugyo District in Western Accepted: January 27, 2019 Uganda. The study was set to examine the gender differences in the level of Published: January 30, 2019 knowledge, attitudes and perceptions about EVD. Methods: The study em- ployed a cross-sectional design using both quantitative and qualitative data Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. -

The Rapture in Twenty Centuries of Biblical Interpretation

TMSJ 13/2 (Fall 2002) 149-171 THE RAPTURE IN TWENTY CENTURIES OF BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION James F. Stitzinger Associate Professor of Historical Theology The coming of God’s Messiah deserves closer attention than it has often received. The future coming of the Messiah, called the “rapture,” is imminent, literal and visible, for all church saints, before the hour of testing, premillennial, and, based on a literal hermeneutic, distinguishes between Israel and the church. The early church fathers’ views advocated a sort of imminent intra- or post- tribulationism in connection with their premillennial teaching. With a few exceptions, the Medieval church writers said little about a future millennium and a future rapture. Reformation leaders had little to say about prophetic portions of Scripture, but did comment on the imminency of Christ’s return. The modern period of church history saw a return to the early church’s premillennial teaching and a pretribulational rapture in the writings of Gill and Edwards, and more particularly in the works of J. N. Darby. After Darby, pretribulationism spread rapidly in both Great Britain and the United States. A resurgence of posttribulationism came after 1952, accompanied by strong opposition to pretribulationism, but a renewed support of pretribulationism has arisen in the recent past. Five premillennial views of the rapture include two major views—pretribulationism and posttribulation-ism—and three minor views—partial, midtribulational, and pre-wrath rapturism. * * * * * Introduction The central theme of the Bible is the coming of God’s Messiah. Genesis 3:15 reveals the first promise of Christ’s coming when it records, “He shall bruise you on the head, And you shall bruise him on the heel.”1 Revelation 22:20 unveils the last promise when it records “He who testifies to these things says, ‘Yes, I am coming quickly,’ Amen. -

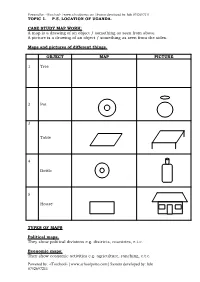

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

BANKABLE-PROJECTS-2.Pdf

3RD EDITION • VIABLE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES 2019/20 UGANDA - Reference Map S U D A N 0 50 100 150 200 km KOBOKO KAA BONG Moyo YUMBE Kaabong MOYO KITGUM Koboko Yumbe Kitgum Adjumani Page Arua ADJUMA NI Kotido ARUA Kibali PADER Gulu Pader KOT IDO GULU Town Okok MOROT O Moroto Nebbi NEBBI Acuwa APAC Oker D E M O C R A T I C Lira Apac LIRA Amuria R E P U B L I C Victoria Nile O F T H E C O N G O AMURIA U G A N D A Katakwi Nakapiripirit MASINDI Lake Lake Kwania Kaberamaido KATAKWI Albert Masindi Soroti NAKAPIRIPIRIT Bunia Amolatar Lake Shari Hoima Kyoga Kumi NAKASONGOLA Kapchorwa HOIMA KUMI 14 Nakasongola Sironko 13 KAMULI Pallisa Bukwa 12 KIBOGA NAKASEKE Kayunga Nkusi PALLISA Lugo KALIRO Mbale BUNDIBUGYO Victoria NileKamuli Kibaale Kiboga Kaliro Butaleja 10 11 Luweero 7 Manafwa KIBAA LE IGANGA 8 Bundibugyo Nakaseke 6 TORORO Fort Portal Iganga Kyenjojo Tororo Mubende JINJA KABAROLE KYENJOJO MIT YA NA Wakiso Jinja MUBENDE Bugiri Nzola Semliki Mukono Mayuge 9 Busia Kakamega Kasese Kamwenge Masaka Mityana MUKONO KAMPALA MAY UGE Katonga MPIGI Mpigi K E N Y A KASESE WAKISO BUGIRI Sembabule Ibanda Kisumu KIRUHURA MASAKA Lake Kalangala Winam Gulf Edward BUSHENYI Kiruhura Masaka Bushenyi KALANGALA Lake 4 Mbarara Victora Rakai 2 Rukungiri Kanungu ISINGIRO RAKAI Ntungamo Kasese 5 1 Kabale U N I T E D Kisoro 3 R E P U B L I C O F RWA N D A T A N Z A N I A Legend Elevation (meters) 5,000 and above National capital 4,000 - 5,000 First administrative level capital 3,000 - 4,000 Populated place 2,500 - 3,000 2,000 - 2,500 International boundary 1,500 - 2,000 First administrative level boundary 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 Districts 600 - 800 400 - 600 1. -

State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2

CONTENTS State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Methodology 5 3.0 Country Context 6 3.1 Political Economy 6 3.2 Political Enviroment 6 3.3 ICT Status 7 3.4 State Co-ownership of Network Operators and Infrastructure 8 3.5 Legal Protection of Human Rights 9 3.6 Status of ICT Legislation 11 4.0 Overview of Information Controls in Place 13 4.1 Content Controls in Legislation 13 4.1.1 Offensive Communication 14 4.1.2 Pornographic or Obscene Content 15 4.1.3 Hate Speech 16 4.1.4 Defamation 17 4.1.5 False Information “Fake news” 18 4.1.6 National Security and Terrorism 19 4.1.7 Censorship 20 4.1.8 Internet Shutdowns 21 4.1.8 Other Restrictions 22 5.0 Internet Intermediaries and Internet Freedom 23 5.1 Limitation of Liability on Intermediaries 23 5.2 Imposition of Liability on Intermediaries 24 5.3 Restrictions Imposed by Intermediaries 26 5.4 Violation of Privacy Rights 28 5.4.1 Processing and Disclosure of Personal Information 28 5.4.2 Retention of Content Data 29 5.4.3 Surveillance and Interception of Communication 30 5.4.4 Poor Accountability of Intermediaries 32 5.5 Inadequate Complaint Handling Frameworks and Remedies 33 5.6 Pushbacks Against Violations and the Promotion of Rights 34 6.0 Conclusion and Recommendations 36 6.1 Conclusion 36 6.2 Recommendations 37 6.2.1 Government 37 6.2.2 Intermediaries 38 6.3.3 Media 38 6.3.4 Academia 38 6.3.5 Technical Community 39 6.3.6 Civil Society 39 6.3.7 Public 39 3 State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 1.0 Introduction Growing use of the internet and related technologies has provided new spaces for advancing the right to freedom of expression (FOE), promoted access to information, and spurred innovation and socio-economic growth in various African countries.